Antarctica: Are we awakening a sleeping giant?

- The seventh continent remains a vast and forbidding wilderness, far and detached from our everyday thoughts.

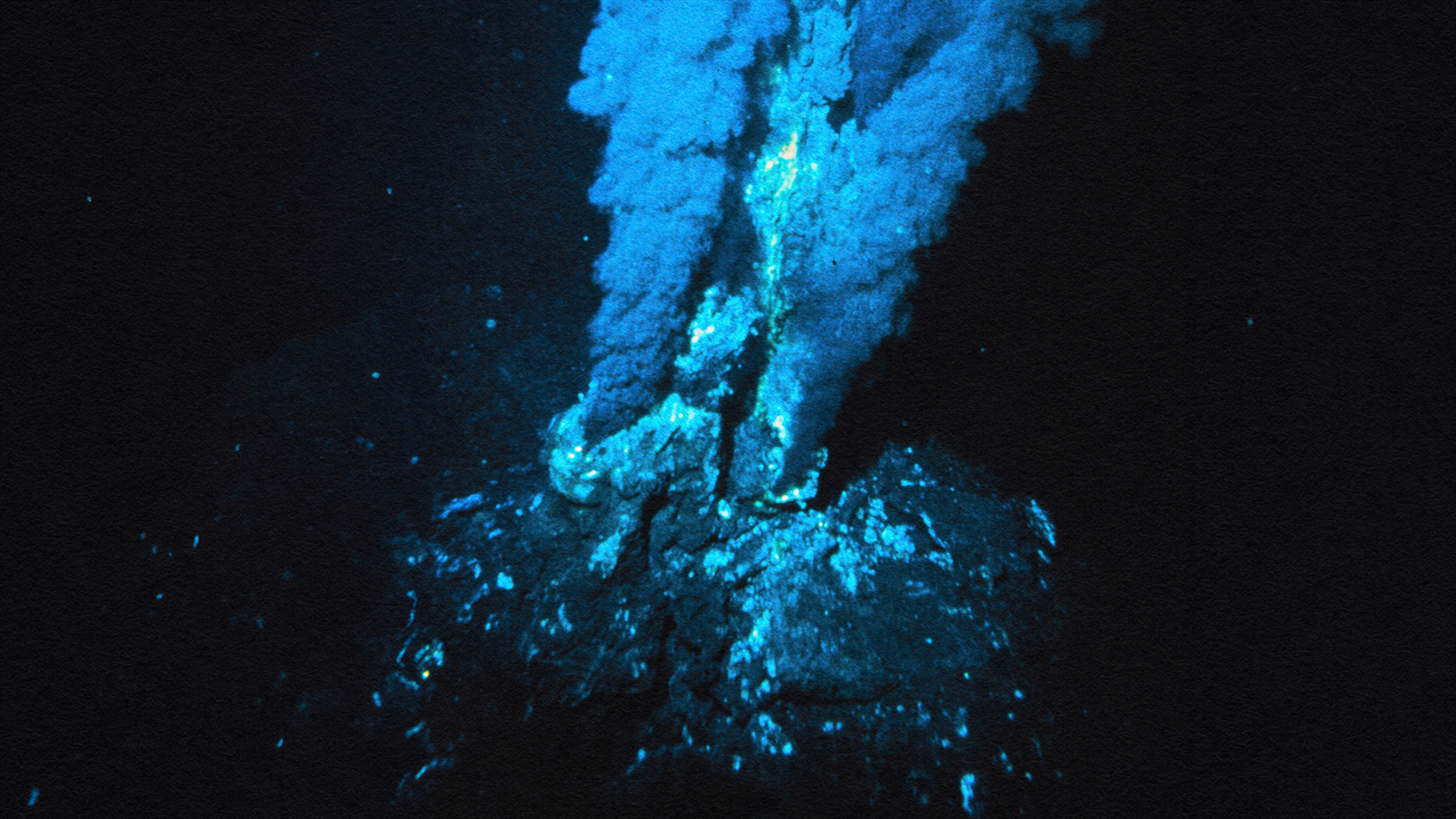

- There we witness the magnificence of life’s engine intertwined with planetary-scale rhythms that work to sustain our world.

- Antarctica is both a lesson on how nature works when balanced and an alarm to what can happen when it doesn’t.

Over the past couple of weeks, I had the privilege to visit the Antarctic Peninsula as well as some of the adjacent islands and research centers. Needless to say, Antarctica is a place of wonder, of grandiose landscapes that words have trouble describing, of a still-wild splendor we rarely see on the planet. Glaciers sprout vertically 100 feet or more from the blue icy waters, surrounded by enormous, jagged peaks reaching thousands of feet. I’m sharing a few photos, which fail to give the proper sense of scale. The experience of being there sends you back into a distant past when our presence was not so pervasive across the world.

Its isolation is part of the challenge of getting there. Crossing the Drake Passage from the tip of Patagonia to the Antarctic Peninsula is no joke. We were on a smallish ship with 140 passengers and, according to the crew, very lucky with the weather. Still, it was normal to encounter waves 15 feet tall crashing violently against the ship from seemingly all directions. Winds reached easily 50 miles per hour. There was not enough Dramamine.

But aside from the majestic landscapes, what is truly remarkable is the life we see there. Antarctica has almost no terrestrial life, with very few plants apart from green and pinkish snow algae and some Arctic grass. Everything revolves around the ocean and what it provides. All animals are sea animals and together they create a balanced food chain that goes from the humble phytoplankton and the krill (a kind of little shrimp) to penguins, sea birds, seals, and, of course, the magnificent whales.

The krill eat the phytoplankton and everything else eats the krill. During feeding season (which lasts for about 120 days), a single humpback whale eats about 2 tons of food per day, most of which is krill. Blue whales may eat 6 tons of krill per day. That’s a lot of krill. And then, of course, orcas eat a lot of stuff but are seen less and less in these parts. This delicate equilibrium is contingent on the climate, the ocean temperature, and, of course, fishing. And yes, the krill population is declining fast and this affects the whole Antarctic food chain. There is no single country or organization responsible for policing the Antarctic waters for illicit fishing.

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet

This is where articles on climate change and human environmental predation start to lose their readers. People don’t want to hear about the negative effects of climate change, overpopulation, and environmental decay. To me, at least, this remains a great mystery. Given that we completely depend on this planet for our existence — from the water we drink and the air we breathe to the stability of land and oceans — this deliberate detachment from nature always struck me as nonsensical.

Is it really just about making money? Is it the inconvenience of changing our diets or habits? Is it ignorance, intentional or not? I thought a lot about this while I was down there, and though there isn’t a single answer, one is certainly a self-imposed physical and cognitive distance. We don’t need to go to the end of the world to experience nature. But we surround ourselves with the familiar, the protective environment of our homes and cities, of our habits and choices. Everything else, such as stories from faraway places, sounds just like that — tales from faraway places that don’t concern us directly.

We rarely if ever have the opportunity to go to a pristine place like this to witness what nature does without us (well, mostly without us since over 150,000 people are now visiting Antarctica per year), to witness a world where few humans have been. But even though the expedition group of 140 travelers was very heterogeneous, the reaction was unanimous: Awe is the word that comes first to mind, and then beauty, harmony, and balance, as we witness the dynamical equilibrium of a complex living system with many inter- and codependent operating parts. It is awesome to witness the engine of life intertwine with planetary-scale feedback of oceanic and atmospheric currents to create a living, breathing world. It places the magnificence of our planet on a totally different level.

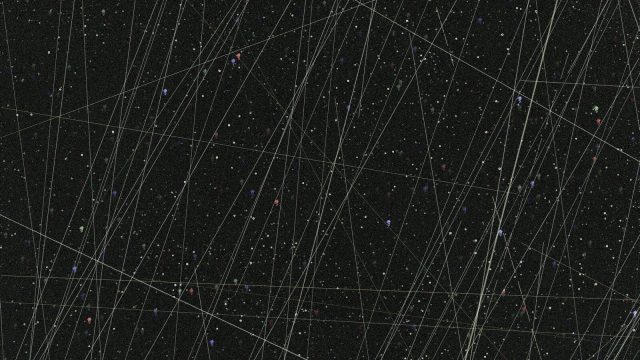

In 2009, Johan Rockström at the Stockholm Resilience Centre introduced a framework for understanding the nine planetary systems that sustain life on Earth. He identified their boundaries and tipping points, beyond which collapse becomes inevitable, irreversible, and unpredictable. One of the sleeping giants, all now stirring into awakening, is the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which, if melted, could raise global sea levels by 10 feet, with devastating consequences for coastal communities around the world.

As we cruised around countless bays on our small zodiacs, often surrounded by groups of five to 10 humpback whales and albatrosses with 9-foot wingspans, witnessing icy glacier walls slowly crumbling into the ocean with thunderous cracks and splashes, we stopped here and there, cut the engine, and just listened in for a few minutes. A silent prayer of gratitude for the gifts this world gives to us every second of our lives — if only we pay attention.