The lies that skulls told us

Once upon a time, people believed you could ascertain a person’s character and personality traits by examining the bumps and shapes of their skull. Such study was called phrenology and its proponents were not just people on the fringe; established scientists beieved such a “science” had merit.

“In origin [phrenology] was distinctly medical,” writes Robert E. Riegel in a 1933 article published in The American Historical Review. “Its originators being the doctors François Joseph Gall and John Gaspar Spurzheim, who did the greater part of their work in the first two decades of the century.”

Gall received his doctorate in 1785 and became “a successful, well-connected, private physician in Vienna,” writes John Van Wyhe in an article in The British Journal for the History of Science. He supposedly rejected an offer to become the personal physician to Emperor Franz II to “preserve his independence,” and found inspiration in a theory on “mind-body dualism” put forward by philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder. Subsequently, Gall set out to prove this theory—that the mind and body are linked—and collected human and animal skulls, made wax molds of brains and skull surfaces, and became something of a “local celebrity” owing to his skull collection (some 300 in number). Before long, the government accused Gall of endangering morality and religion, and forbade him from lecturing on the subject. It was at one such lecture that Spurzheim met Gall. Starting in 1804, for about eight years the two collaborated until Spurzheim started offering his own take on the system and called it “phrenology” from phren, the Greek word for “mind.”

While Spurzheim toured Britain—a celebrity lecture series of sorts—phrenology found a new home. Everyone from Charlotte Brontë and George Eliot to Arthur Conan Doyle bought into it. Between 1823 and 1836, phrenologists established twenty-four dedicated societies with 1,000 members, and published a whopping fifty-seven books and pamphlets, amounting to 64,250 volumes.

In 1836, Hewett Watson, a prominent botanist (and, later, phrenologist) foresaw that future naysayers would be laughed at. “Public pity will be freely bestowed upon the anti-phrenologists,” Watson wrote. “[A]nti-phrenology will exist in the last decrepitude of age […] it will be a subject for the historians of things that have ceased to be.”

What’s more, phrenology was supported by people Watson esteemed, including the Anglican Archbishop of Dublin, Richard Whately, who declared “Phrenology is true as…the sun is now in the sky.”

The irony is delicious.

For a while though, phrenology thrived. In 1850, even Queen Victoria and Prince Albert invited phrenologist George Combe to the palace to read the heads of their children. Combe—who introduced phrenology to the British middle classes in the 1820s through his lecture tours—examined the Prince of Wales, Edward VII. Then aged 9, the Prince was doing poorly in his studies. Later still, a phrenologist was appointed as tutor to Prince Alfred, Queen Victoria’s second son.

For their part, phrenologists believed abstract behavioral attributes including, firmness, hope, sublimity, destructiveness “could be localized to specific convolutions on the brain surface and that the representation of these attributes could be inferred by palpation of the skull,” writes James Ashe in The Quarterly Review of Biology.

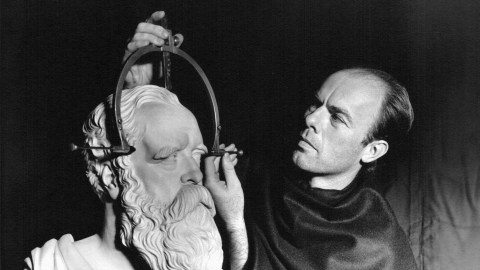

Although phrenology was largely spread through glorified lecture tours, it wasn’t long before university professors taught this pseudoscience to medical students alongside anatomy. Phrenologists primarily used tape measures and craniometers—semi-circular tools to measure the cranium–as well as calipers to reach their diagnoses. With the advent of electricity, some phrenologists used “psychographs,” circuited helmets that would take “readings” of skulls.

George Combe divided the skull into 33 “organs,” or regions, each associated with a different attribute. For instance, organ one—the back of your neck—Informed sex drive, while region 23—above your brow—indicated skin color and tone. It’s from this that the term “highbrow” came to reflect intellectual superiority.

It’s also why the study of the shapes, bumps, and curvature of people’s heads is tied to racist, sexist, and classist beliefs. Phrenology thrived during the height of the British Empire, a power defined largely by its dependence on servility and enslavement. Employing a “science” that perpetuated myths about white supremacy helped justify its imperialism.

According to an article in The Atlantic, other words that originated in phrenology include “shrink” (as in, to get one’s head shrunk to manage or reduce “undesirable” traits), “stuck up” (snobby) and “hard headed.”

Eventually, phrenology crumbled owing to its lack of scientific rigor. “After the passing of the early figures of the movement…little time was spent on the necessary scientific research,” writes Robert E. Reigel. “Much time was spent [by phrenologists] in elaborating phrenological doctrines and in applying them to education, marriage, [and] racial relations.”

In marriage, for instance, it was noted that the “devoted wife and mother” had a pronounced curve to the back of her head and neck, where the “childless lover of children” did not. Interestingly, this gave rise to various trends in hairstyles and overexaggerations of phrenologically appealing features in art, including the works of sculptor Hiram Powers.

Still, as it waned in England, it found new life in the United States. In as early as the 1830s, Harriet Martineau noted that when Spurzheim came to New England, “the mass of society became phrenologists in a day.”

Given the claims phrenology made about white racial superiority, phrenology was embraced in antebellum America, writes Peter McCandless in The Journey of Southern History. “One of [Spurzheim’s] disciples, Dr. Jonathon Barber, soon took the gospel to Charleston and other southern cities.” By the 1830s and 1840s the city’s bookshops sold the works of Spurzheim and Combe as an ode to their own appetite for intellectualism in the subject.

Phrenology would soon find mentions across American literature, from Whitman to Poe whose Fall of the House of Usher is peppered with phrenological double entendres: Roderick’s “ inordinate expansion above the regions of the temple,” for instance, reflects his ideality and cautiousness accounting for his melancholy, writes Brett Zimmerman.

In the United States phrenology was considered a tool for self-improvement. Celebrated American phrenologists included the Fowler Brothers, Walt Whitman, Lorenzo Niles and Orson Squire, the former of whom “phrenologized” young Clara Barton. Of Barton, who would later become a nurse and the founder of the American Red Cross, L. N. Fowler said: “She will never assert herself for herself . . . but for others she will be perfectly fearless. Throw responsibility upon her.” The phrenologized diagnosis would go on to be quoted in magazine articles and Barton’s own memoir.

As in England, however, phrenology’s success in the States rapidly declined “undermined by science’s popular successes,” notes McCandless. Developing and evolving scientific methodologies required more than a map of the skull. While science prevailed, phrenologists persisted to a degree writes Riegel, preying on the desperate and impressionable. The end of phrenology gave rise to the “practical phrenologist,” he notes.

“This practitioner, frequently without training, sought to capitalize the new science and make it pay dividends,” Riegel says. “He was a fortune teller.”

This article appeared on JSTOR Daily, where news meets its scholarly match.