Soon, You’ll Know As Much About What You Buy As the Company That Made It

The term “Big Data” naturally conjures up images of Big Users, like the government or Google or Costco. It’s easy to see why big enterprises crunch data to learn, for example, which groceries people want on the first day of a heat wave and which they want later on, or how warmed-up Scots buy different foods than people on a hot day in England, or how your recent Facebook activity hints that you’re in the market for a new printer. But Big Data is now so abundant and accessible that it can also be used by us smallfolk. Case in point: Buycott, a new app for smartphones that scans a product code and tells you in an instant who will profit if you buy the thing. Don’t want to help the Koch brothers make more money? Want to reward companies that took your preferred position on Internet freedom or marriage equality? Just scan and tap.

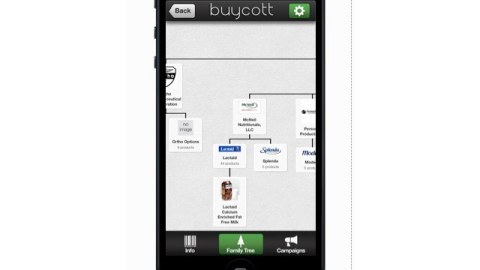

Ivan Pardo, a Los Angeles programmer, created Buycott to help people create and maintain campaigns. So, as Clare O’Connor explains here, people who want labels on products that use genetically modified foods can scan a box at the grocery store and immediately know if the maker (or its parent company, or parent company’s parent company) is one of 36 firms that spend money to defeat labelling proposals. And as you boycott the bad guys, you can also “buycott”—make sure you help fill the coffers of companies you agree with. For instance, O’Connor points out, if you support marriage equality you can use Buycott to scan vodka bottles, and find one made by a company that is on the record in favor, like Absolut.

Buycott is also, of course, pretty interesting to non-boycotters and buycotters—it lifts a veil of ignorance between shoppers and the processes and substances that went into the stuff those shoppers are invited to buy. (So, Brawny Paper Towels are made by Georgia Pacific, which is owned by…Koch Industries. Maybe you knew that. I didn’t.

Even if you did know it, I would bet a lot that you don’t know all the companies that profit from your consumer choices, or what those companies are doing politically and economically. Who has the time to gather such data? Once it’s possible to do so in an instant, on-demand, though, there is a qualitative change in the way people relate to the goods they consume.

In pre-industrial times, people had an almost personal relationship to their stuff. If they hadn’t made it themselves, then they knew the craft-person who had, and they knew what he or she had used to make it. Industrial manufacturing drew a curtain between maker and user, and globalization made it more opaque. Labels tell me my son’s toy was made in China, or my shirt in Bangladesh. Occasionally, when a disaster or a scandal exposes bad working conditions, we in the rich world ask ourselves about the hidden connections. Did child labor make these shoes? Did exploited workers assemble this phone? Are the rare earths in this tablet helping to support endless war in Congo?

The more data we can get about the making of our stuff, the more these general-sounding questions can get specific answers. This could well lead to major changes in how people see the goods they consume, and how they then behave.

For example: we know, as Paul Bloom writes here, that people easily feel empathy for individuals, but not for whole populations. (As the psychologist Paul Slovic has mordantly put it, the more who die, the less we care.) So how about an empathy-promoting app that shows you the name and photo of the person who assembled your new pants, or that new toy? Such software is, I suspect, well within the capacity of the systems that monitor the global supply chain. Or, consider another possibility: Right now, many Americans associate “Made in Bangladesh” with the Rana Plaza building collapse. Imagine, instead, being able to know for certain if a particular pair of pants was made in that notorious place—or, instead, in a safer factory.

In the longer term, this kind of detailed data, in the hands of consumers, would likely bring about vast changes in their behavior. People might well get used to targeting their spending so as to never put money in the pockets of companies they don’t approve of. And what will become of advertising in a world where we can look behind the images of a computer to see the factory where it was made, the workers who assembled it, and the miners who dug the earth for its components?

Illustration: Buycott displays the corporate “family tree” of a scanned product.

Follow me on Twitter: @davidberreby