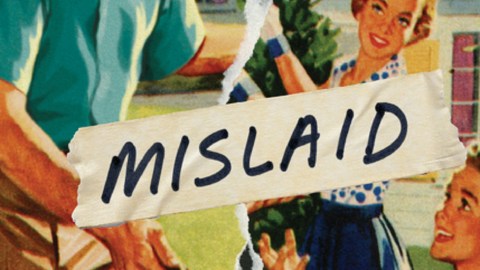

Southern Gothic Punk: Reading Nell Zink’s ‘Mislaid’

If Flannery O’Connor somehow birthed the love child of Sid Vicious, she might end up sounding like novelist Nell Zink. Equal parts Southern Gothic’s grotesquely twisted charm and punk and alternative music’s insiderish anti-establishmentism, Zink’s second novel Mislaid will disorient you until you let it delight you. Zink’s mix — which I’ll call Southern Gothic Punk — might be an acquired taste, but a taste well worth experiencing if only to break out of the contemporary rut of MFA-programed, soundalike fiction that’s become the bubblegum pop of today’s literature.

Zink brings the punk early and often, starting with plot. Here’s the story in a confounding nutshell: A lesbian teen arrives at a Virginia college in 1966 where she has an unlikely affair with a gay poetry professor that leads to children and marriage until she leaves him, taking their daughter away (but leaving behind their son) to live their lives as “passing” African-Americans only to have the children reunite comically at another college years later when the daughter undeservedly wins a minority scholarship to be with her uber-achieving (actually) African-American boyfriend. Got all that? Zink’s gone on record with her disdain for contemporary novel, “look at my MFA degree” plot conventions and claims to model Mislaid instead on “Viennese operetta.” In opera, plot is simply something that gets you to the next tune. In Mislaid, plot is simply something that gets Zink to her next riff. Either way, overthinking plot improbabilities as a listener or reader just gets in the way, so go with it.

When you go with Zink, she takes you on a wild ride. Raised in rural Virginia, Zink mines her personal past for all its worth in Mislaid, providing you with an updated version O’Connor, a Southern Gothic 2.0. The pseudo-heroine Peggy (later, in hiding, Meg) Vaillaincourt descends from family still proud that they sheltered the fleeing assassin John Wilkes Booth. The “Lost Cause” isn’t lost on Zink or her characters, but she manages to maintain the satire without falling into caricature, an amazing feat considering her operatically improbable plot, which increasingly feels right as you delve into her world of wrongs. “Welcome to the No South,” announces one character, denying the very idea of a New (i.e., modern, reconstructed) South. “You can’t have ‘New’ and ‘South.’ It’s oxymoronic … Fat boys used to spend their lives in bed and only come out to fish and hunt. Now they go into politics and make our lives hell.” Zink’s politics may irk some as shrill stereotyping, but for many, they sound like reports from the front lines of the culture wars from a reporter who’s lived on both sides.

Zink aims her keen, satiric eye on multiple targets. She spoofs college life and college students in flowing passages: “The Christian student association sponsored dances, of all things, and its most popular DJ, a Cure fan in flowing hippie skirts, founded a short-lived campus Republican chapter, disbanded when she transferred to UC Santa Cruz to study the history of consciousness.” Mislaid is a target-rich environment for divine comedy. The dark comedy of mother and daughter choosing to live as poor African-Americans in the New/No South and passing despite little Karen’s blonde curls spills out multiple messy truths about race that critics will scurry to clean up with explanations for years. But just when you think you’ve found where Zink’s politics or affections rest, she upsets you with “an outspoken lesbian feminist a la Adrienne Rich (in 1984!)” testifying that nothing’s off limits.

Zink’s finding literary success at nearly 50, but she never really looked or hoped for it. “Whatever I was writing at the time, I knew there was no market for it and never would be,” Zink confessed to The Paris Review, “because there’s never a market for true art, so my main concern was always to have a job that didn’t require me to write or think.” Not caring what people think can be very liberating, as Zink proves, thus bringing the quintessential punk aesthetic to the too comfortable world of contemporary literature. In Mislaid, Lee, the homosexual poet-professor-father figure, explains to aspiring playwright Peggy/Meg that “art for art’s sake is an upper-class aesthetic. To create art divorced from any purpose, you can’t be living a life driven by need and desire.” By divorcing her writing from “true art” goals (and, by extension, the “upper-class aesthetics” of the status quo), Zink paradoxically hits upon a truer art that speaks the impolite truths of someone with nothing to lose because they have nothing they hope to gain.

The only two fields Zink takes seriously are sex and text, mingling the pleasures of both into a whole new definition of “sexting.” Lee thinks “his homosexuality might be a great big cosmic typo” when he falls for Peggy’s androgynous charms. Another character cites his “romantic belief in transcendent submissiveness, borrowed from [Hermann] Hesse’s Steppenwolf” for keeping him virginal until college. One character seductively riffs on Finnegans Wake. In response, Zink writes, “‘Don’t you James Joyce me!’ she said. But it was too late.” Throughout Mislaid, Zink drops the names of favored writers like an indie music fan citing favorite bands nobody else knows. The characters may be sexually “mis-laid” in finding the wrong partners in terms of sexual and spiritual orientation, but literature never betrays the hearts that love it. From low-brow puns on “Bigger Thomas” to higher-brow Paul Bowles references, Zink “James Joyces” you until it’s too late to stop, not that you want her to.

The publicists for Mislaid boldly call the novel’s recognition scene “a darkly comedic finale worthy of Shakespeare,” referring to the Bard’s many plot twists reuniting siblings, lovers, and others. For me, the most Shakespearean aspects of Mislaid recall his rarely read “problem play” Troilus and Cressida. Troilus and Cressida’s fails to find a popular or critical audience because it falls between the easy categories of comedy and tragedy while giving us characters that we can’t wholly hate or praise. But just as some think that play’s finally found its perfect audience today — more accepting of ambiguity and real-life messiness — Zink’s Mislaid gives us operatic, paradoxical, often unattractive characters that we can’t wholly hate or praise, but oddly learn to love.

[Many thanks to Harper Collins Publishers for providing me with the image above from the cover to and a review copy of Nell Zink’s Mislaid.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]