Outlaw Artist: The Curious Case of Mark Augustus Landis

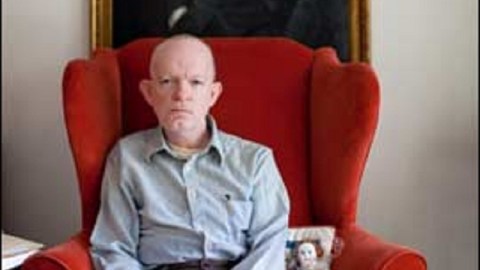

Forgery is the bane of the art world. An artist passes his work off under another artist’s name and reaps financial gain. But what does it mean when a forger practices his trade for art’s sake without accepting a cent in return? In a recent issue of Financial Times, John Gapper documents the curious case of Mark Augustus Landis (shown above), a forger who for the past three decades donned disguises to coax museums across the United States to accept his work as a “donation” done by a name (but not too big a name) artist. As far as anyone can tell, Landis hasn’t broken any laws by asking for nothing in return for his art, but has he violated a different code through his actions? Or has this strange outlaw given a unique testimonial to the power of art to drive an individual to go to any lengths for self-expression?

Gapper rightfully calls Landis’ forgery frolic “the longest, strangest forgery spree the American art world has known.” Landis’ standard modus operandi is to arrange a meeting with a museum posing as a Jesuit priest named Father Arthur Scott. The good Father shows up with a work he wishes to donate in the name of someone else, usually a parent. The work itself typically holds up to the cursory scrutiny of the museum representative accepting the gift. However, professional eyes further down the line often spot discrepancies as the donation is processed into the museum’s collection. It’s unknown how many of Landis’ donations have slipped through the system and maybe even found a place on a gallery wall. Landis usually caps off his priestly performance by bestowing a blessing (in Latin, no less) on the museum. A natural showman, Landis even “blessed” Gapper at the end of their interview.

According to the piece, Landis suffered some psychological breakdown in his youth and most likely is a schizophrenic. Museum personnel often write off Landis’ odd behavior as the same eccentricity exhibited by many art-loving donors. What I found fascinating in the piece was Landis’ choice of artists to mimic. Charles Courtney Curran, Alfred Jacob Miller, Louis Valtat, Marie Laurencin, Milton Avery, Everett Shinn, and even Walt Disney are some of the artists that Landis has tried to pass as—a gamut of styles as strange and befuddling as Landis himself.

With the exception of Disney, all of those artists are good enough to gain entry into most museums but not so notable to attract close attention. Forgers interested in money normally pick big names—Picasso, Matisse, and (in the case of Han van Meegeren) Vermeer—in hopes of a big payday. van Meegeren claimed that the money was just icing on the cake after fooling the same art establishment that had rejected works signed under his own name. Landis may have a similar motivation to gain acceptance previously denied, but the mitigating factor is his “donating” in his parents’ names. It’s as if he scammed the museums not out of resentment but in a strange tribute to his parents. “Look, Ma,” Landis’ works say from the museum walls, like football players mugging into a camera on the sidelines, “I made it.”

van Meegeren became a folk hero of sorts for his forgery. Facing criminal charges after World War II of selling Vermeers to high-ranking Nazis such as Herman Goering, van Meegeren outed himself as a forger to avoid jail, thus gaining heroic stature for having conned the baddest of baddies. Landis may gain folk hero status not for fooling evil (unless you consider museums evil), but instead for questioning whether museums displaying names over actual quality of the work at hand. Landis is probably not much better than a very talented amateur, but the fact that he’s fooled some museums by dropping the right names makes one wonder what artists have been shut out of the system simply because they lacked the right name. In shining light on that possibility, Landis’ blessing on the institution of art museums may be his (perhaps unintentional) challenge to see beyond names to the art itself.