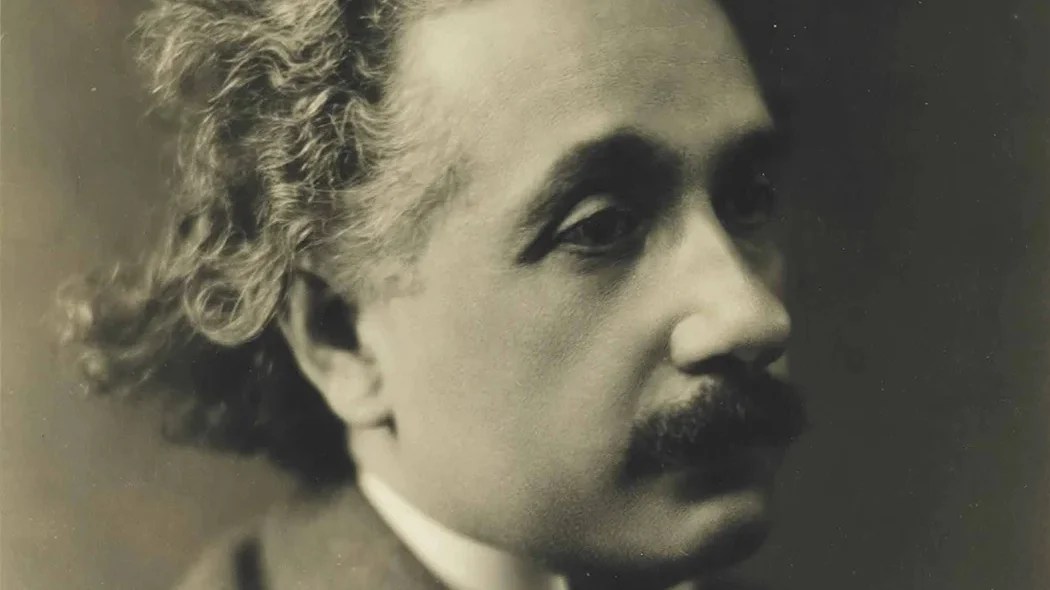

Learn How to Think Like Einstein

Albert Einstein is widely considered one of the smartest people who ever lived, significantly impacting our understanding of the world around us. His General Theory of Relativity has redefined what we know about space and time and is one of the pillars of modern physics. What’s also remarkable about Einstein’s achievements is that they relied largely on his mental powers and the intricacy of his imagination. He was able to discern and relate very complex scientific concepts to everyday situations. His thought experiments, that he called Gedankenexperimentsin German, used conceptual and not actual experiments to come up with groundbreaking theories.

CHASING A BEAM OF LIGHT

One of Einstein’s most famous thought experiments took place in 1895, when he was just 16. The idea came to him when he ran away from a school he hated in Germany and enrolled in an avant-garde Swiss school in the town of Aarau that was rooted in the educational philosophy of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, which encouraged visualizing concepts.

Einstein called this thought experiment the “germ of the special relativity theory.” What he imagined is this scenario – you are in a vacuum, pursuing a beam of light at the speed of light – basically going as fast as light. In that situation, Einstein thought, that light should appear stationary or frozen, since both you and the light would be going at the same speed. But this was not possible in direct observation or under Maxwell’s equations, the fundamental mathematics that described what was known at the time about the workings of electromagnetism and light. The equations said that nothing could stand still in the situation Einstein envisioned and would have to move at the speed of light – 186,000 miles per second.

Artists pose in a laser projection entitled ‘Speed of Light’ at the Bargehouse on March 30, 2010 in London, England. (Photo by Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images)

Here’s how Einstein expanded on this in his Autobiographical Notes:

“If I pursue a beam of light with the velocity c (velocity of light in a vacuum), I should observe such a beam of light as an electromagnetic field at rest though spatially oscillating. There seems to be no such thing, however, neither on the basis of experience nor according to Maxwell’s equations. From the very beginning it appeared to me intuitively clear that, judged from the standpoint of such an observer, everything would have to happen according to the same laws as for an observer who, relative to the earth, was at rest. For how should the first observer know or be able to determine, that he is in a state of fast uniform motion? One sees in this paradox the germ of the special relativity theory is already contained.”

The tension between what he conceived of in his mind and the equations bothered Einstein for close to a decade and led to further advancements in his thinking.

LIGHTNING STRIKING A MOVING TRAIN

A 1905 thought experiment laid another cornerstone in Einstein’s special theory of relativity. What if you were standing on a train, he thought, and your friend was at the same time standing outside the train on an embankment, just watching it go by. If at that moment, lightning struck both ends of the train, it would look to your friend that it struck both of them at the same time.

But as you are standing on the train, the lighting that the train is moving towards would be closer to you. So you would see that one first. It is, in other words, possible for one observer to see two events happening at once and for another to see them happening at different times.

“Events that are simultaneous with reference to the embankment are not simultaneous with respect to the train,” wrote Einstein.

The contradiction between how time moves differently for people in relative motion, contributed to Einstein’s realization that time and space are relative.

Lightning strikes during a thunderstorm on July 6, 2015 in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

MAN IN FALLING ELEVATOR

Another thought experiment led to the development of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity by showing that gravity can affect time and space. Here’s how he described it happened:

“I was sitting in a chair in the patent office at Bern when all of a sudden a thought occurred to me,” he remembered. “If a person falls freely, he will not feel his own weight.” He later called it “the happiest thought in my life.”

A 1907 thought experiment expanded on this idea. If a person was inside an elevator-like “chamber” with no windows, it would not be possible for that person to know whether he or she was falling or pulled upward at an accelerated rate. Gravity and acceleration would produce similar effects and must have the same cause, proposed Einstein.

“The effects we ascribe to gravity and the effects we ascribe to acceleration are both produced by one and the same structure,”wrote Einstein.

One consequence of this idea is that gravity should be able to bend a beam of light – a theory confirmed by a 1919 observation by the British astronomer Arthur Eddington. He measured how a star’s light was bend by the sun’s gravitational field.

THE CLOCK PARADOX AND THE TWIN PARADOX

In 1905, Einstein thought – what if you had two clocks that were brought together and synchronized. Then one of them was moved away and later brought back. The traveling clock would now lag behind the clock that went nowhere, exhibiting evidence of time dilation– a key concept of the theory of relativity.

“If at the points A and B of K there are clocks at rest which, considered from the system at rest, are running synchronously, and if the clock at A is moved with the velocity v along the line connecting B, then upon arrival of this clock at B the two clocks no longer synchronize but the clock that moved from A to B lags behind the other which has remained at B,“ wrote Einstein.

This idea was expanded upon to human observers in 1911 in a follow-up thought experiment by the French physicist Paul Langevin. He imagined two twin brothers – one traveling to space while his twin stays on Earth. Upon return, the spacefaring brother finds that the one who stayed behind actually aged quite a bit more than he did.

Einstein solved the clocks paradox by considering acceleration and deceleration effects and the impact of gravity as causes of the for the loss of synchronicity in the clocks. The same explanation stands for the differences in the aging of the twins.

Time dilation has been abundantly demonstrated in atomic clocks, when one of them was sent on a space trip or by comparing clocks on the space shuttle that ran slower than reference clocks on Earth.

How can you utilize Einstein’s approach to thinking in your own life? For one – allow yourself time for introspection and meditation. It’s equally important to be open to insight wherever or whenever it might come. Many of Einstein’s key ideas occurred to him while he was working in a boring job at the patent office. The elegance and the scientific impact of the scenarios he proposed also show the importance of imagination not just in creative pursuits but in endeavors requiring the utmost rationality. By precisely yet inventively formulating the questions within the situations he conjured up, the man who once said “imagination is more important than knowledge” laid the groundwork for the emergence of brilliant solutions, even if it would come as a result of confronting paradoxes.