Water can become two different liquids, prove researchers

Credit: Pixabay

- Water can be in two liquid states under cold temperatures, shows new research.

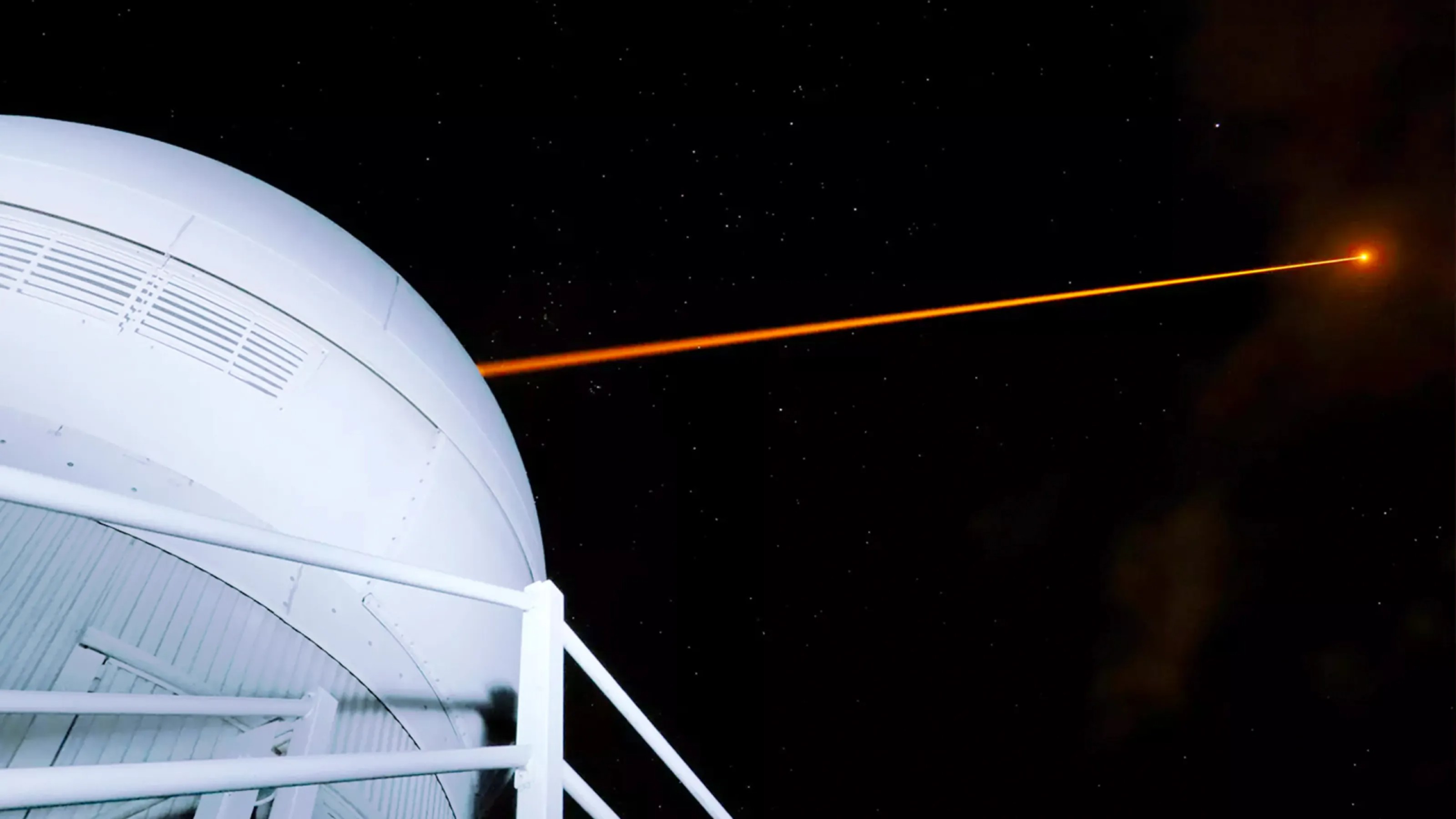

- The scientists used x-ray lasers and computer simulations.

- The discovery has applications across a variety of fields due to water’s ubiquity.

Water is an essential life force for humanity and our planet. But despite it’s omnipresence, there’s much we have still to learn about the fateful combination of hydrogen and oxygen atoms that comprises this near-magical substance. Now a new study proves water can have two different liquid states, in one of its most unusual properties.

The research, carried out by an international team of researchers, involved sophisticated experiments with x-ray lasers and computer simulations. The team, led by chemical physics professor Anders Nilsson from Sweden’s Stockholm University, also included CUNY professor Nicolas Giovambattista. He explained in a press release that while it’s been proposed about 30 years ago that water may have two different liquid states, this “counterintuitive hypothesis” was been hard to prove, due to the complexity of the experiments necessary. Ice tends to form at the conditions when the two liquids should exist.

The liquid state of water that we all know and encounter in our daily lives is how water behaves at regular temperatures – around 25 degrees Celsius (77 F) . What the new study showed is that at low temperatures of around -63 degrees C (-81 F), water can be found in two states: a low-density liquid at low pressures, and a high-density liquid at high pressures.

“What was special was that we were able to X-ray unimaginably fast, before the water froze, and could observe how one liquid transformed to the other”, said professor Nilsson.

The researchers found that the difference in density between the two liquids was about 20 percent. A thin interface would form, given the right conditions, to separate the two kinds of water without mixing them. A similar phenomenon to what you observe when oil and water are combined.

Kate the Chemist: Water is a freak substance. Here’s why. | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

The scientists think their find can affect a variety of scientific and engineering uses of water. “It remains an open question how the presence of two liquids may affect the behavior of aqueous solutions in general, and in particular, how the two liquids may affect biomolecules in aqueous environments,” Giovambattista explained. “This motivates further studies in the search for potential applications.”

Besides CUNY and Stockholm University, scientists from POSTECH University in Korea, PAL-XFEL in Korea, SLAC national accelerator laboratory in California, and St. Francis Xavier University in Canada were also involved in the study.

Check out their new study in the journal Science.