50 years ago, an artist convincingly exhibited a fake Iron Age civilization

Invented civilizations are usually thought of as the stuff of sci-fi novels and video games, not museums.

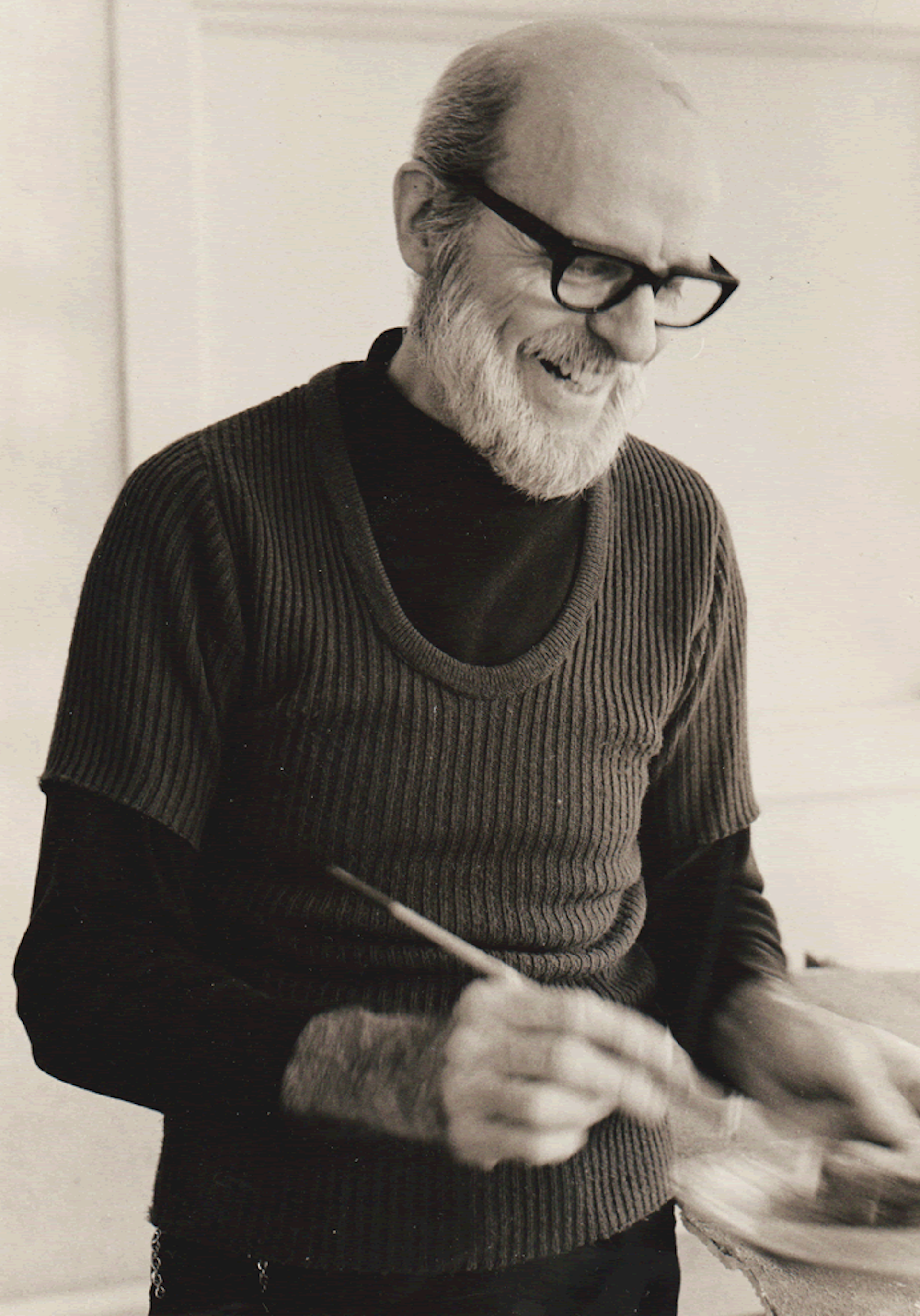

Yet in 1972, the Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art at Cornell University exhibited “The Civilization of Llhuros,” an imaginary Iron Age civilization. Created by Cornell Professor of Art Norman Daly, who died in 2008, the show resembled a real archaeological exhibition with more than 150 objects on display.

Unaware of Llhuros, I started fabricating and documenting my own imaginary ancient culture using ceramics and printmaking for my undergraduate thesis in 1980. The following year, as a graduate student, I learned about Llhuros and began a decadeslong correspondence with Daly.

With scams, deceptions and lies flourishing in our digital age, an art exhibition that convincingly presents fiction as fact has particular currency.

A culture made from scratch

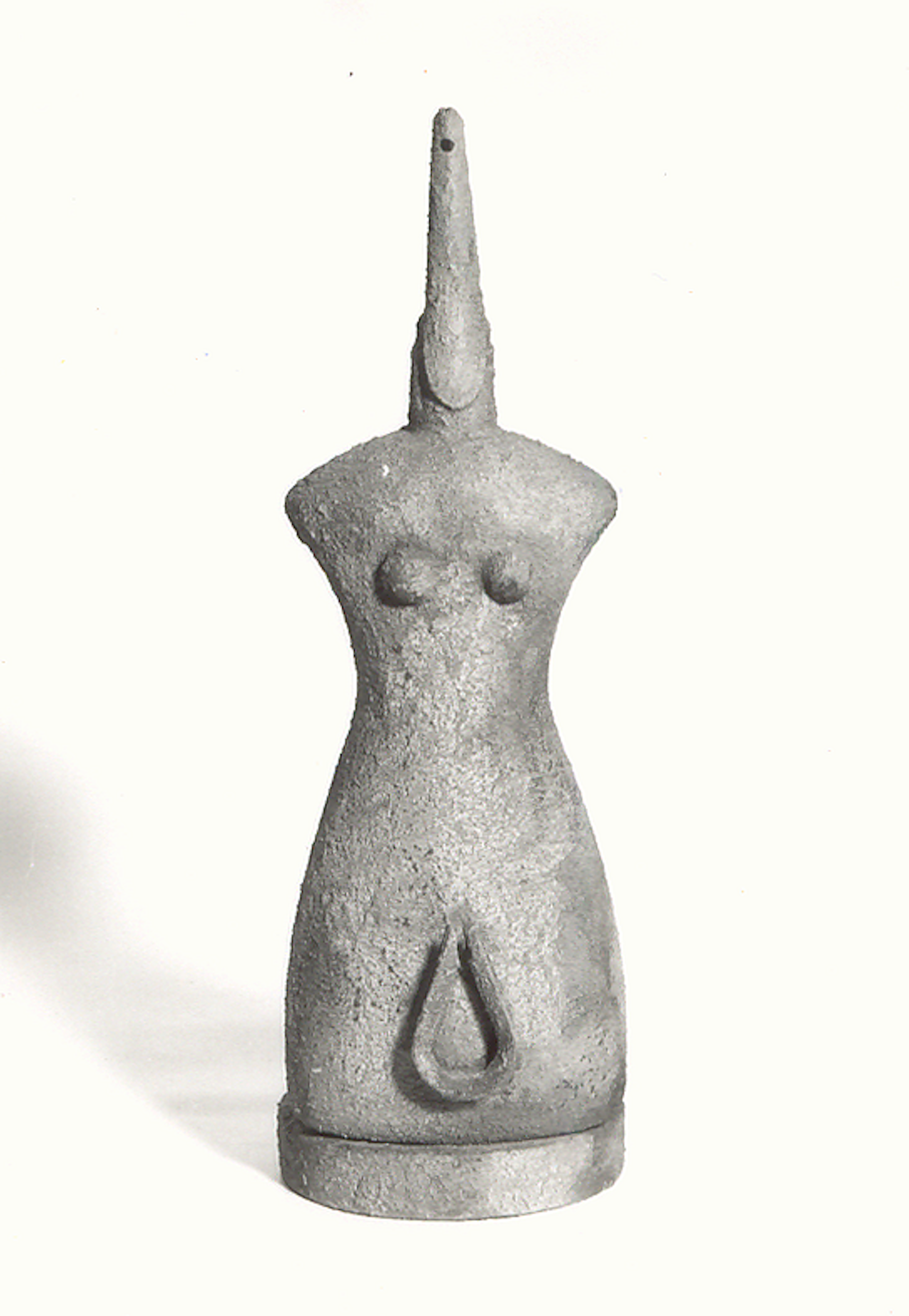

Daly’s project was truly groundbreaking. The exhibition included a map of the excavation sites, old tools and religious artifacts that Daly had crafted, all from the culture’s distinct periods – “Early Archaic,” “Archaic,” “Late Archaic,” “Middle Period” and “Decline.”

There were translations of Llhuroscian poetry that Daly had written; soundtracks with reenactments of Llhuroscian ceremonies and songs performed by a women’s church choir; audio interviews with fake Llhurosian scholars; and a 56-page exhibition catalog with an invented bibliography and glossary of Llhuroscian terms.

Daly – with guidance from Marilyn Rivchin, a museum staffer; and Robert Ascher, a Cornell anthropology and archaeology professor – conceived everything.

To the casual viewer, Llhuros appeared to be real. The artifacts and tools were often made from found objects – an Ivory dish-soap bottle transformed into an earthenware figure, or a “nasal flute found at the early excavations at Lamplö” made from a metal stove burner. Many of the objects were cracked and broken, with patinas and incrustations making them appear as if they’d survived centuries. The tension between real and fake was tangible.

At the time, the exhibition attracted enthusiastic reviews in Newsweek and The New Republic. But the New York art world largely overlooked it.

Testing the viewer’s grasp of reality

Prior to creating “The Civilization of Llhuros,” Daly was making paintings and sculptural reliefs influenced by Native American and prehistoric art.

His earlier work had much in common with other 20th century artists, from Pablo Picasso to Max Ernst, who drew inspiration from art outside of the European canon. These artists questioned Western academic traditions and valued the direct and expressive forms found in African and Native American art. This approach to making art can be problematic, since there’s an element of cultural appropriation. But it also speaks to a desire to connect with universal aspects of human culture.

So why would Daly shift his creative practice to the mock-documentary form, creating an entire fake culture in the form of a museum exhibition?

A few key moments cultivated the idea.

One of his tall sculptural works had been exhibited in a faculty dining room. But people kept mistaking it for a hat rack, which frustrated Daly: He assumed that the value of an artwork was self-evident and that it should be able to “speak for itself.” Clearly, that wasn’t always the case. So by creating an exhibition – replete with a catalog, visual guides and explanatory labels – he could extend the meaning of his visual art. If the art object does not speak for itself, why not fabricate a narrative as part of the show?

Another realization came to Daly while attending a performance of contemporary music. At the concert, he observed that the audience was working hard to resist the random interference of auditory distractions, from program rustlers to feet shufflers. Daly considered ways that a visual artist could employ what he called “planned interference” to provoke deeper audience engagement with the work.

This insight compelled him to use a variety of ironic signals to disrupt the credibility of the museum narrative and test the viewer’s understanding whether Llhuros was real or invented. He might assemble a massive bronze temple door from plastic foam packing cartons, or create an oil lamp that resembles an orange juicer.

For Daly, stories about the Llhuroscians are also about what it is to be human, with themes of guilt, desire and faith appearing in many of the works. With his recurring “stilt walker,” he depicts a religious pilgrim who carries a bird on his head, walking on stilts of different lengths. The self-imposed struggle of the man, who appears across several works, comes from the guilt he feels.

The art of fraud

Like Daly, I was interested in the use of documentary forms to present works of fiction. My mock-documentary exhibitions have shifted from archaeological themes to include anatomical prints, a collection of contemporary folk art, a creationist organization from the 1920s, and an early 20th century circus. I am drawn to this form of art because I am inspired by the idea of inventing artworks that appear to have the authority of history.

In her 2021 book, “Sting in the Tale: Art, Hoax and Provocation,” artist and writer Antoinette LaFarge describes Daly’s approach as a form of “fictive art,” arguing that the mock-documentary uses of historical forms, as well as “self-outing” through ironic signals, have significance for a contemporary culture saturated with misinformation.

There are, of course, precedents: In his 1917 bathtub hoax, journalist and satirist H.L. Mencken presented a fabricated history of bathtubs in America. P.T. Barnum became known for his creative hoaxes, which included his Feejee mermaid specimen, made from an orangutan and a salmon. Where Mencken sought to teach the American public about their gullibility, Barnum wanted to make a quick buck and didn’t care whether his audience believed the ruse. Fictive art draws on this history to create relevant works of contemporary art.

To mark the 50th anniversary of “The Civilization of Llhuros,” I have organized a free, daylong virtual symposium to be held on Oct. 8, 2022. An international roster of presenters will discuss Daly’s exhibition and his legacy as a teacher. It will also feature contemporary artists who work with Llhuros as a paradigm.

Today, fact-checking outlets and algorithms help people spot deception and misinformation. But art that tests your perceptions of what is real – allowing you to suspend your disbelief, while also giving you the opportunity to recognize the tools of deception – can play a role, too.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.