“Global Jukebox” database uncovers secrets from the history of music

- The Global Jukebox is a database that contains recordings of more than 5,000 traditional folk songs.

- Linked to other databases, the publicly available dataset allows researchers to study the history and co-evolution of music and society.

- One interesting finding is that song lyrics become less repetitive as society becomes more complex.

Until recently, people studied music history the same way they studied art history or history in general: by evaluating individual sources (in this case, different forms of song and music) and comparing them to other sources from a different time or place. Today, music historians are able to study their subject with large data sets, using sources like the Global Jukebox to process unprecedented amounts of information to discover truths that were overlooked or simply indiscernible.

The Global Jukebox

The Global Jukebox is an online database containing sound files of 5,776 traditional songs from over 1,026 societies, categorized by musical style, number of singers, vocal establishment, breath management, instrumentation, rhythm, and melody. Global Jukebox, which after years of development was recently turned into a publicly available resource for academics all over the world, even contains data on things that aren’t necessarily related to music, such as conversation styles.

The Global Jukebox is not the first of its kind. Cultural anthropologists first started organizing information into large datasets during the late 20th century. Among the first of these datasets was the Ethnographic Atlas, a collection of data on social structure, economy, kinship, and religion compiled by American anthropologist George Peter Murdock in 1967. The Ethnographic Atlas was followed by other resources, such as the Human Relations Area Files for ethnographic research, and Ethnologue and Glottolog, both for linguistic diversity.

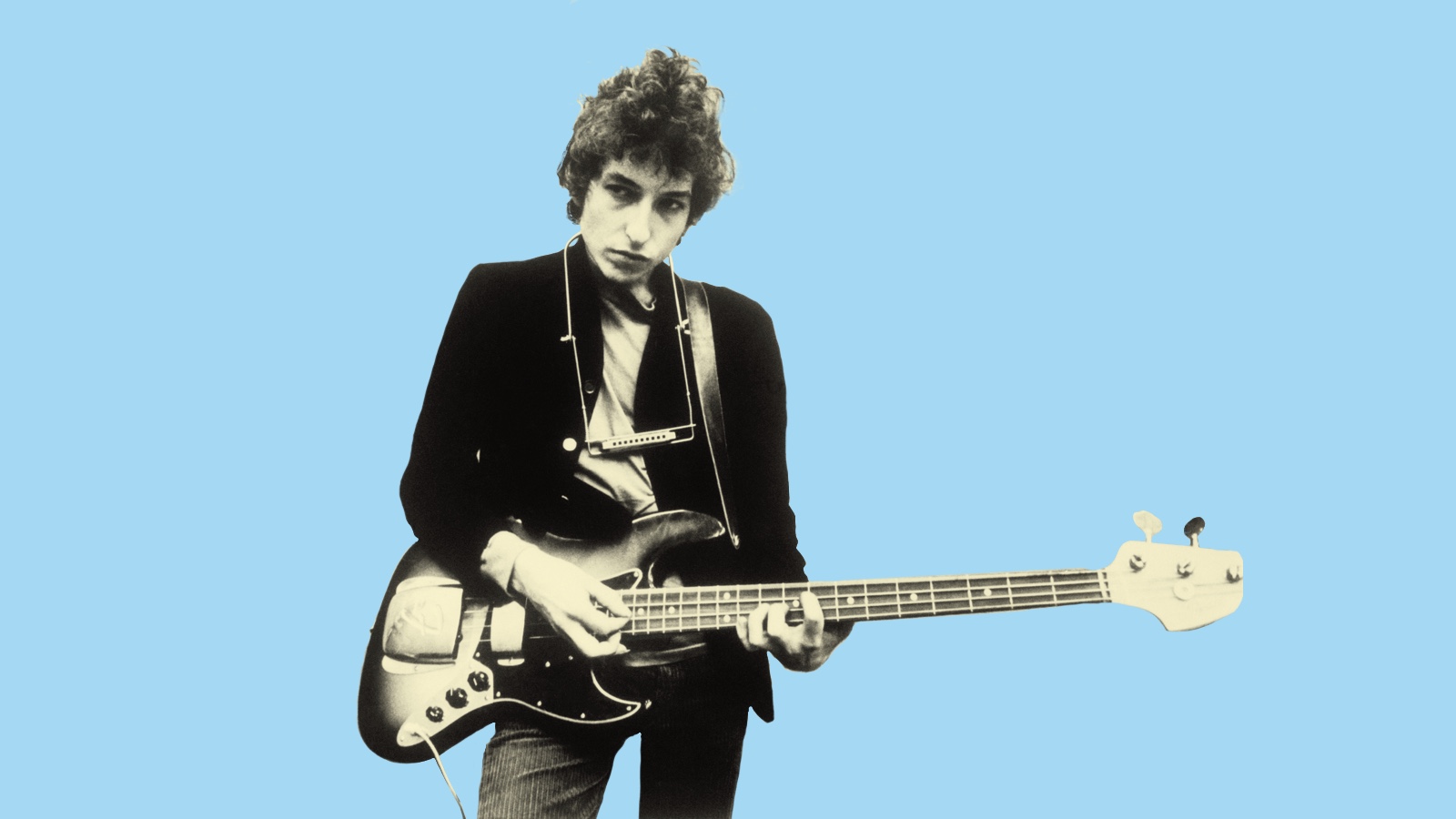

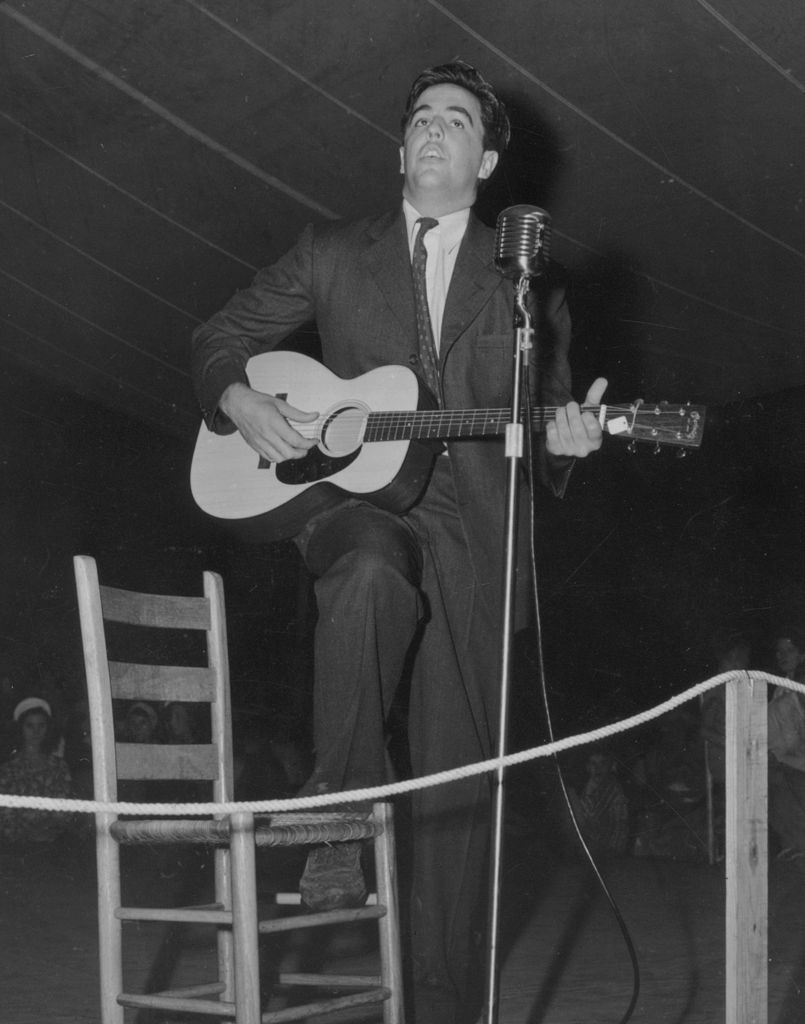

The creators of the Global Jukebox, ethnomusicologists Alan Lomax and Conrad Arensberg, began collecting data about traditional songs for their Expressive Style Research Project, which was carried out through Columbia University. At Columbia, the two developed “cantometrics,” an approach to music history that relies on and works through organized, cross-cultural datasets. When computers entered the workplace in the 1980s, Lomax and Arensberg uploaded their datasets to the web, where they gradually evolved into an interactive multimedia platform.

After a test launch in 2017, Global Jukebox is now online and ready to use. In the time leading up to the release, a team of researchers led by Anne Lomax Wood — daughter of Alan, from whom she inherited the project — refined the dataset to improve accuracy. The availability of recordings is limited by copyright laws as well as the preferences of some small cultural groups.

Saving endangered songs

“Access is so important,” Wood said in a statement. “More than anything else, my father wanted people who are being cut off from their ancestral cultures — drowned, as under the waters of a new dam — to hear their songs and to find their aesthetic footprint in their own ‘big traditions.’ So while the Global Jukebox is highly technical, it is also a place everyone can explore.”

Wood’s colleague, Patrick Savage, hopes Global Jukebox will be of use to “scientists interested in understanding cultural diversity, members of the original communities wanting to strengthen their traditions, and members of the general public wanting to learn more about the beauty and diversity of all the world’s music.”

Before the Global Juke Box was released, Wood also cross-indexed its entries with another resource, the Database of Peoples, Languages, and Cultures. D-Place, as it is also called, contains mostly non-musical data about societies. The link between these databases, says Wood, allows researchers to analyze the coevolution of aesthetic patterns in music and other types of traditions.

The power of Global Jukebox

To illustrate the potential of the Global Jukebox, Wood and her team investigated the link between song styles and societal complexity. The results of the investigation were published alongside an introduction to Global Jukebox in the jo”How Bob Dylan used the ancient practice of“urnal PLoS One.

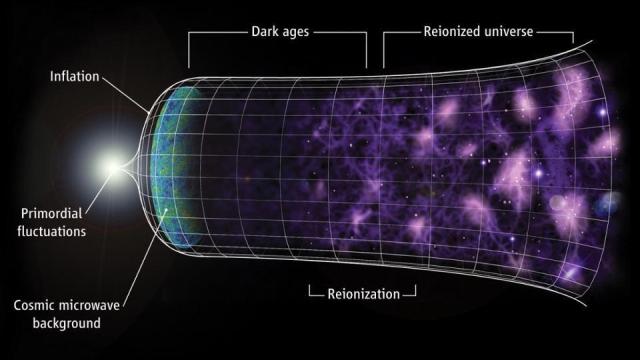

The hypothesis that Wood tested was initially put forward by her father, who cross-referenced his prototypical Global Jukebox with the Ethnographic Atlas to find no less than five different correlations between the style of a song and the level of social complexity exhibited by the people that made it. He wrote:

“Song style tends to grow more articulated, ornamented, heavily orchestrated, and exclusive as societies grow bigger, more productive, more urbanized, and more stratified. Specifically, (1) the level of text repetition decreases directly as productivity increases, (2) the level of precision of enunciation increases as states grow in size, (3) the prominence of small intervals and embellishments indicates the level of stratification, (4) orchestral complexity symbolizes state power, and (5) melodic form and complexity reflect the size and subsistence base of a community.”

Critics of Lomax wondered whether these correlations reflected a causal relationship, or simply existed due to similarities between cultures and shared ancestry. To investigate, Wood analyzed the updated, cross-referenced Global Jukebox.

How society influences music

Wood’s team specifically found that:

- Musical organization increases with more jurisdictional hierarchy;

- Text repetition declines with more productive subsistence technologies;

- Embellishment increases with stratification;

- Melodic intervals decline with larger community size; and

- Enunciation becomes more precise with higher levels of jurisdictional hierarchy

“These results,” the article states, “suggest that the way we make music is guided by the musical traditions of our ancestors and our neighbors, and is also related to societal structure.”

But while the authors have ruled out the possibility that the correlations arise due to shared ancestry, they cannot yet prove whether the relationship is causal. “We do not believe,” they continue, “that social factors directly produce effects upon music… However, the probability that certain social and musical traits and configurations will consistently co-occur raises questions about what drives aesthetic preferences. For example, are aesthetic preferences embodied in vocal representations of emotions and / or physical states that may arise under certain persistent conditions?”

Maybe, with help from Global Jukebox, another team of researchers will be able to answer that question in the future. The database will only become more comprehensive as time goes on and more sound files are added. Up next, its caretakers plan to upload song recordings for underrepresented regions, such as Polynesia.