You can respond to verbal instructions in your sleep

- We can process information and learn in our sleep.

- New research shows that we also can respond to verbal instructions.

- The findings could offer new ways of studying sleep-related mental problems.

It is generally assumed that sleep is a state of unconsciousness, during which we disconnect from, and become completely unresponsive to, our surroundings. Recent research shows, however, that we can process information while we sleep, and that this sleep-learning can exert implicit influences on our behavior when we are awake.

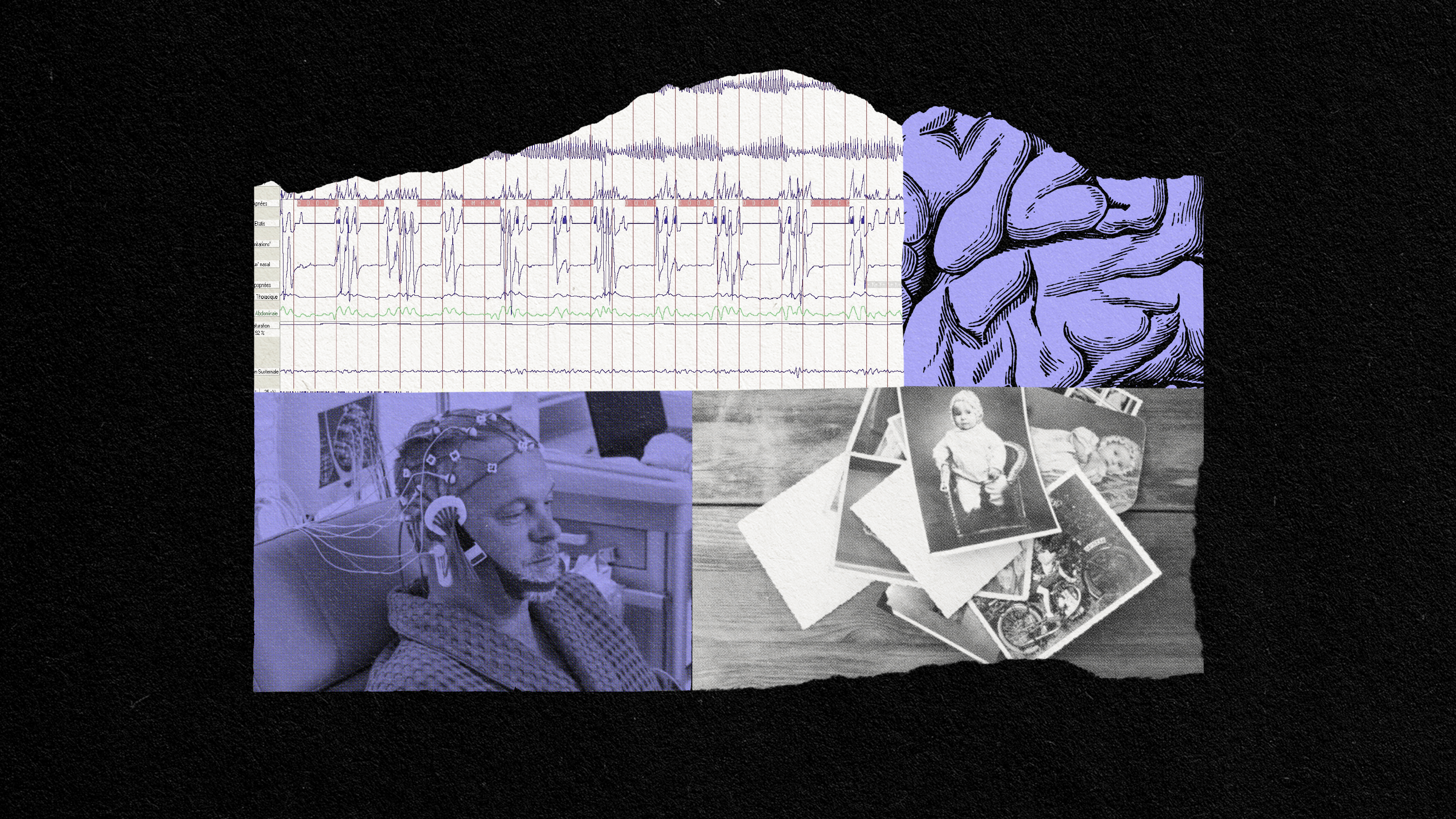

Most of this research demonstrates that the processing of sensory information during sleep occurs automatically and unconsciously. Several years ago, however, Başak Türker of the Paris Brain Institute and her colleagues showed that they could initiate two-way communication with lucid dreamers. Their findings, published in 2021, showed that lucid dreamers were able to answer yes-or-no questions, discriminate between sights, sounds and textures, and perform mathematical calculations during the rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleep.

The same research team now shows that their earlier findings extend not only to non-lucid dreamers, but also to other sleep stages. In a new study published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, they report that people can also perceive and respond to verbal instructions while they sleep.

You are getting sleepy

For this latest study, Türker and her colleagues recruited 49 participants, 27 of whom have narcolepsy, and played them a series of words and “pseudo-words,” presented in semi-random order, while they napped in a sound-proof room. The participants were required to decide if each word was real or made up, and respond with facial expressions: smile if the word was real one, frown if it was made up. During the experiment, the researchers used electrodes to measure the electrical activity of each participant’s brain, heart, and facial muscles.

The electrode recordings showed that all the participants were significantly more responsive during those periods in which they heard words and pseudo-words than during the “off” periods when they heard nothing. They responded to the verbal stimuli during all sleep stages, with their responsiveness increasing with the depth of sleep.

Responsiveness was also associated with, and preceded by, increased neural activity in regions of the brain linked to high cognitive states, such that the researchers could predict when the participants would respond to the verbal stimuli by surges in brain activity.

After waking from each nap, the participants were asked to describe any mental content they experienced while they slept, whether they had a lucid dream, and whether they recalled performing the task. Only those participants with narcolepsy, which is characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and increased lucid dreaming, reported having lucid dreams. Interestingly, lucid dreaming was associated with an increase in the neural activity associated with cognition, above and beyond that seen with the responses that occurred during non-lucid dreaming.

Talking to sleepers

The researchers conclude that “transient windows of reactivity to external stimuli exist during bona fide sleep,” and that lucid dreamers may have “privileged access to their inner world,” with “heightened awareness… to the outside world.” They also suggest that these windows could offer a way of communicating with sleepers to study sleep-related mental problems.