How Not To Evaluate a Teacher

In January, Andrew Cuomo, the governor of New York, threw down the gauntlet on education in his State of the State Address:

“Last year, less than 1 percent of teachers in New York State were rated ineffective; but state test results show that statewide only 35.8 percent of our students in third through eighth grades were proficient in math and 31.4 percent were proficient in English Language Arts. We must ask ourselves: How can so many of our students be failing if our teachers are all succeeding?”

The huge gap between teacher excellence and student success looks very fishy, the governor suggested. It’s implausible that 98.7 percent of teachers are truly “effective” or “highly effective” when so many of their students fail to show basic competence in reading and mathematics. “Who are we kidding, my friends?” Cuomo concluded. “The problem is clear and the solution is clear. We need real, accurate, fair teacher evaluations.”

Sounds logical, until you realize the governor is actually kidding himself. In August 2013, the New York State education commissioner noted that on the new Common Core-aligned tests, “the percentage of students deemed proficient is significantly lower” than it was the previous year and that this result was “expected.” The drop in scores, the commissioner emphasized, does “not reflect a decrease in performance for schools or students.” Now Gov. Cuomo is saying exactly the opposite. He is blaming teachers for lower test scores on a new battery of tests that everyone knew would be much harder to pass than the previous ones.

In the governor’s eyes, two main reforms are needed to make evaluations “real, accurate, and fair.” First, standardized test scores need to be weighted more heavily in teachers’ evaluations than the current rate of 20 percent; Gov. Cuomo wants to increase that share to 50 percent. Second, “local score inflation” — where milquetoast principals purportedly goose bad teachers’ scores to save their jobs — needs to be nipped in the bud. Principals’ assessments of their teachers, currently factored as 60 percent of teachers’ scores, shrink to a token 15 percent under Gov. Cuomo’s plan. The remaining 35 percent of the evaluation would be based on outside evaluators’ assessments.

I’m sympathetic to the governor’s view that teachers need to be held accountable, and I agree that testing data ought to play some role in the system of accountability. The question is what role that should be, and whether test results should be weighted so heavily. It is dismaying that after parents, students, and teachers demonstrated widely and vehemently against Gov. Cuomo’s education plan this week, the governor’s spokesman said, “[F]rankly, the louder special interests scream — and today they were screaming at the top of their lungs — the more we know we’re right.” Notice how the governor’s office somehow turns public school parents, teachers, administrators, and students into “special interests.” And note how this response fails to display the scholarly virtues of open-mindedness and critical reasoning that public schools aim to instill in their students.

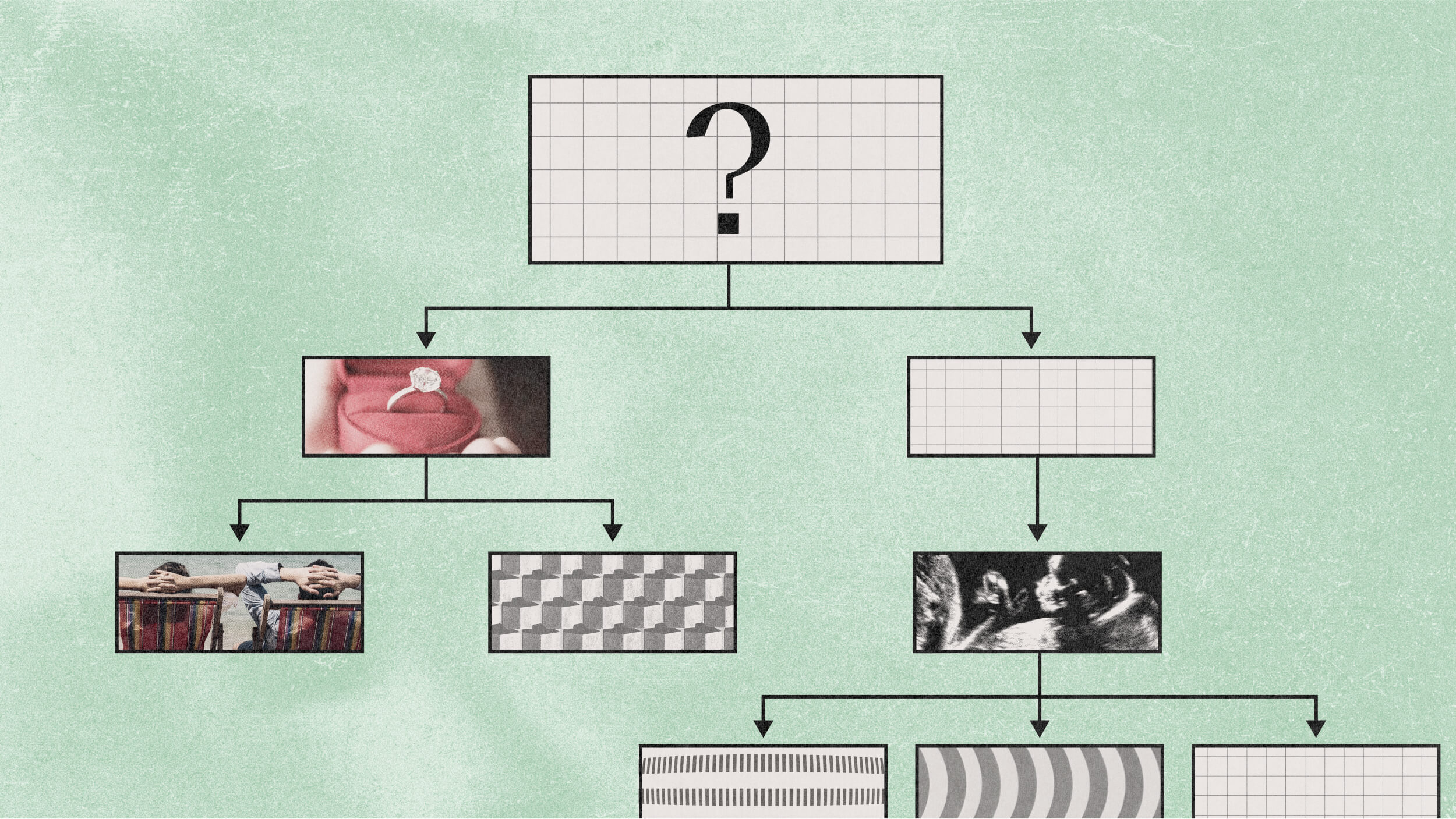

Many commentators have explained how damaging it can be to tie teacher evaluations to students’ test results. “With their livelihoods potentially in jeopardy over … minor variation[s]” in test scores, Rebecca Mead writes at The New Yorker, “teachers will be obliged to teach to the test” rather than, as New York City’s Mayor Bill de Blasio says, “teaching for learning.” And the increasingly popular “value-added assessment models,” which purport to measure teacher effectiveness based on how their students’ test scores change over time, have been condemned by the American Statistical Association. The models “measure correlation, not causation” and “foster a competitive environment, discouraging collaboration and efforts to improve the educational system as a whole.” To add to the absurdity, up to 50,000 teachers in New York City (75 percent of the total) will be evaluated based on how students they have never met perform on tests in subject matters they do not teach. Why? Many faculty, including kindergarten through second grade teachers and music and art teachers, teach subjects or grades that are not linked to a standardized state test. In order to provide the state with missing data points to evaluate those educators, students’ scores for their fellow teachers serve as proxies. It’s conceivable that thousands of teachers could lose their jobs based on declining test scores for students who never show up in their classrooms.

There has been less commentary on the second prong of Gov. Cuomo’s proposed reforms: bringing in outside evaluators to rate teachers while largely roping local school administrative staff out of the process. This idea threatens schools more glaringly still. For me, as a teacher at a public New York City secondary school, the recently expanded procedure whereby principals and assistant principals visit teachers’ classrooms has had a notable silver lining. School administrators may be overburdened by hundreds of class visits and incessant logging of data points, and the rubric by which teachers are evaluated may be from ideal, but there is a very bright spot in the system that has been in place since 2013: frequent, formal, reflective conversations between faculty and administration about teaching.

This dialogue — which includes goal-setting and frank discussions following formal observations — is just the kind of exchange that keeps teachers on their toes and keeps principals in the loop about their faculty. Done right, the dialogue promotes collegiality and enhances morale. It encourages teachers to be more thoughtful about their teaching, and gives teachers opportunities to discuss their craft with their school leader.

Few of these benefits would be possible with occasional visits from a random outside observer. An outsider does not know the culture of the school. He does not know each teacher’s story, or how teachers may be developing in their careers from year to year — working on designing a better math assessment, say, or teaching the Federalist Papers more lucidly. He would not notice if a teacher managed to draw out a notoriously quiet student in a class discussion or if he aided a student who has trouble paying attention in other classes to focus on a task. An outside “expert” would, in short, be clueless as to the daily nuances of life in a particular school, in a particular classroom, in an interaction between a teacher and student. And the ratings and feedback he would offer would be lacking in the context that educators desperately need to hone their skills.

I don’t doubt that Gov. Cuomo’s reforms stem from a genuine concern for the thousands of young New Yorkers who are being dealt a disservice by their schools. He is right that the current teacher-evaluation system could be better: It should be more streamlined and less punitive, with more opportunities for thoughtful collaboration and professional development. But the way to evaluate a teacher is not by making him fear for his job lest some of his, or his colleagues’ students (whether high-achieving or not) drop a few points on state exams. And assessing an educator is not best accomplished by subjecting him to qualitative evaluations by people who have no idea who he is or what he is trying to do.

Image credit: Shutterstock.com