What is the true nature of our quantum reality?

- In the classical Universe, objects exist with specific properties that they continue to possess regardless of whether or how recently they’ve been observed.

- In the quantum Universe, however, many properties remain in an indeterminate state until a critical measurement, observation, or interaction forces the issue.

- While many have argued over which interpretation best reflects reality, you can forget Copenhagen, Many-Worlds, Pilot Waves and all the others. What remains is what’s truly real.

When it comes to understanding the Universe, scientists have traditionally taken two approaches in tandem with one another. On the one hand, we perform experiments and make measurements and observations of what the results are; we obtain a suite of data. On the other hand, we construct theories and models to describe reality, where the predictions of those theories are only as good as the measurements and observations they match up with.

For centuries, theorists would tease novel predictions out of their models, ideas and frameworks, while experimentalists would probe uncharted waters, looking to validate or refute the leading theories of the day. With the advent of quantum physics, however, all of that began to change. Instead of specific answers, only probabilistic outcomes could be predicted. How we interpret this has been the subject of a debate that’s lasted nearly a century. But having this debate at all may be a fool’s errand; perhaps the very idea that we need an interpretation is itself the problem.

For thousands of years, if you wanted to investigate the Universe in a scientific fashion, all you had to do was figure out how to set up the right physical conditions, and then making the critical observations or measurements would give you the answer.

Projectiles, once launched, follow a specific trajectory, and Newton’s equations of motion enable you to predict that trajectory to arbitrary accuracy at any moment in time. Even in strong gravitational fields or close to the speed of light, Einstein’s extensions of Newton’s theories enabled the same outcome: provide the initial, physical conditions to arbitrary accuracy and you can know what the outcome, at any point in the future, is going to be.

Until the end of the 19th century, all of our best physical theories describing the Universe followed this path.

Why did nature appear to behave this way? Because the rules that governed it — our best theories that we had concocted to describe what we measure and observe — all obeyed the same sets of rules.

- The Universe is local, which means that an event or interaction can only affect its environment in a way that’s limited by the speed limit of anything propagating through the Universe: the speed of light.

- The Universe is real, which means that certain physical quantities and properties (of particles, systems, fields, etc.) exist independent of any observer or measurements.

- The Universe is deterministic, which means that if you set your system up in one particular configuration, and you know that configuration exactly, you can perfectly predict what the state of your system is going to be at an arbitrary amount of time into the future.

For more than a century, however, nature has shown us that the rules governing it aren’t local, real, and deterministic after all.

We learned what we know today about the Universe by asking the right questions, which means by setting up physical systems and then performing the necessary measurements and observations to determine what the Universe is doing. Despite what we might have intuited beforehand, the Universe showed us that the rules it obeys are bizarre, but consistent. The rules are just profoundly and fundamentally different from anything we’d ever seen before.

It wasn’t so surprising that the Universe was made of indivisible, fundamental units: quanta, like quarks, electrons, or photons. What was surprising is that these individual quanta didn’t behave like Newton’s particles: with well-defined positions, momenta, and angular momenta. Instead, these quanta behaved like waves — where you could compute probability distributions for their outcomes — but making a measurement would only ever give you one specific answer, and you can never predict which answer you’ll get for an individual measurement.

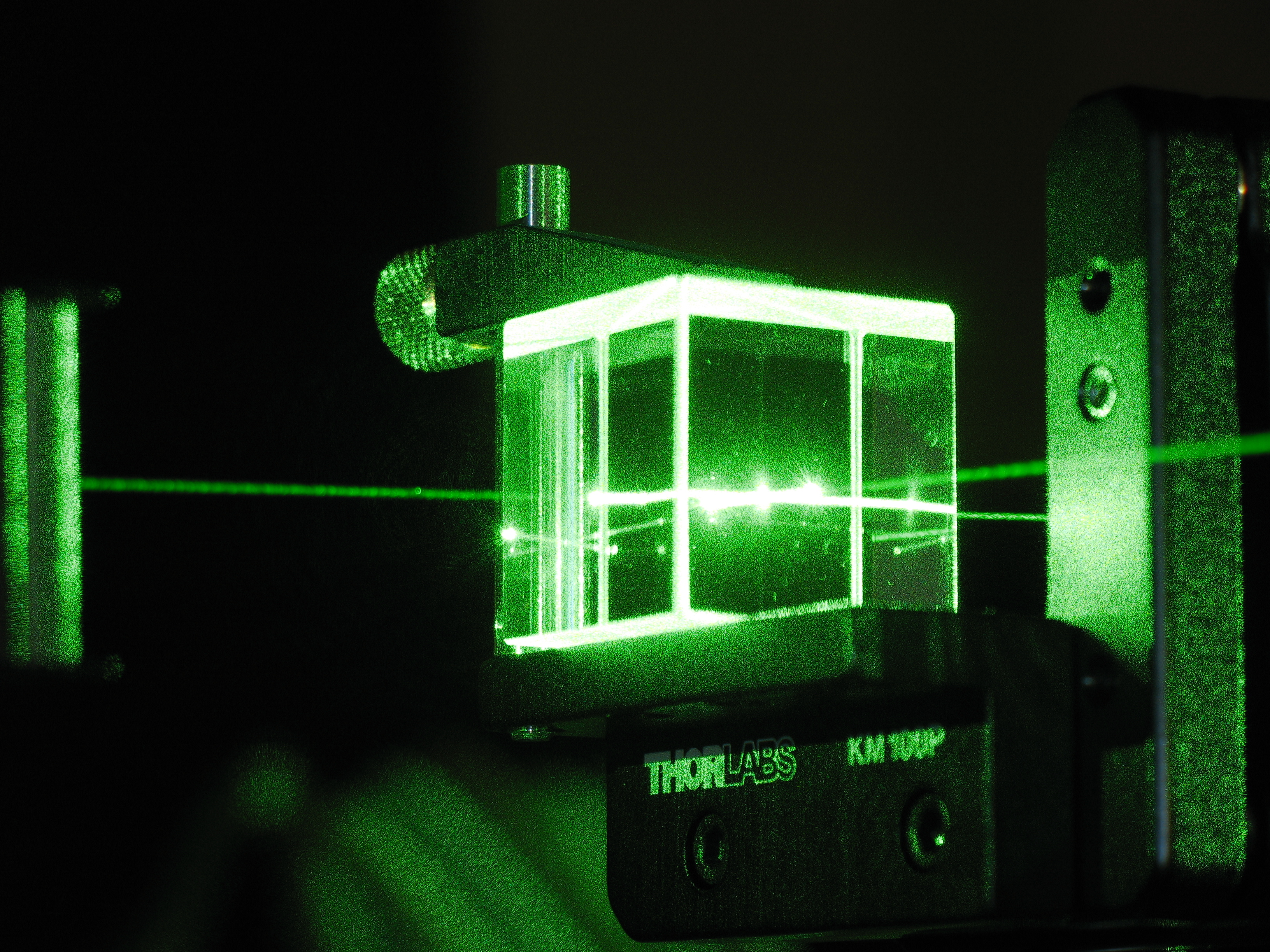

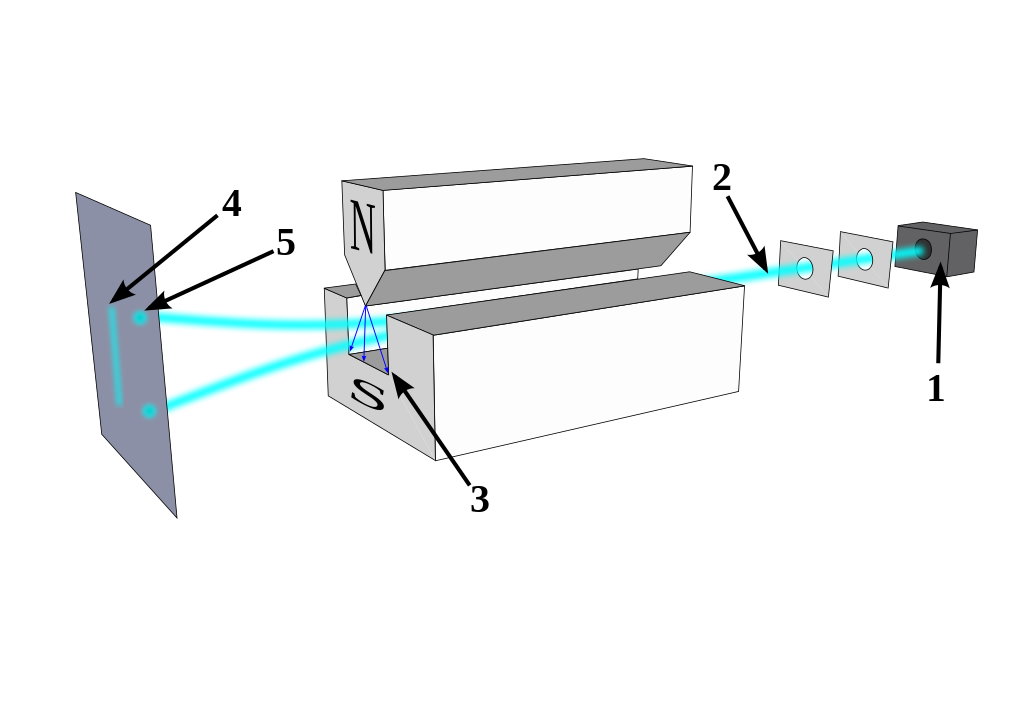

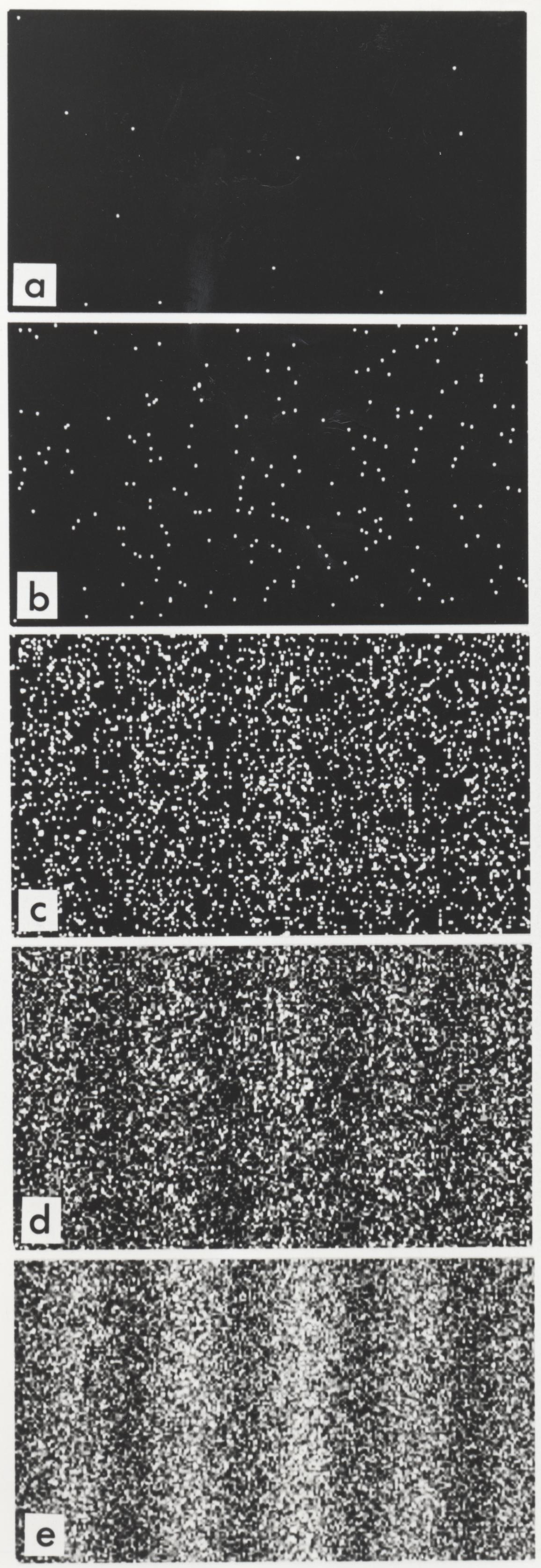

This has been borne out by a huge variety of experiments. A particle like an electron, for example, has an inherent spin (or angular momentum) to it of ±½. You cannot eliminate this intrinsic angular momentum; it is a property of this quantum of matter that cannot be extricated from this particle.

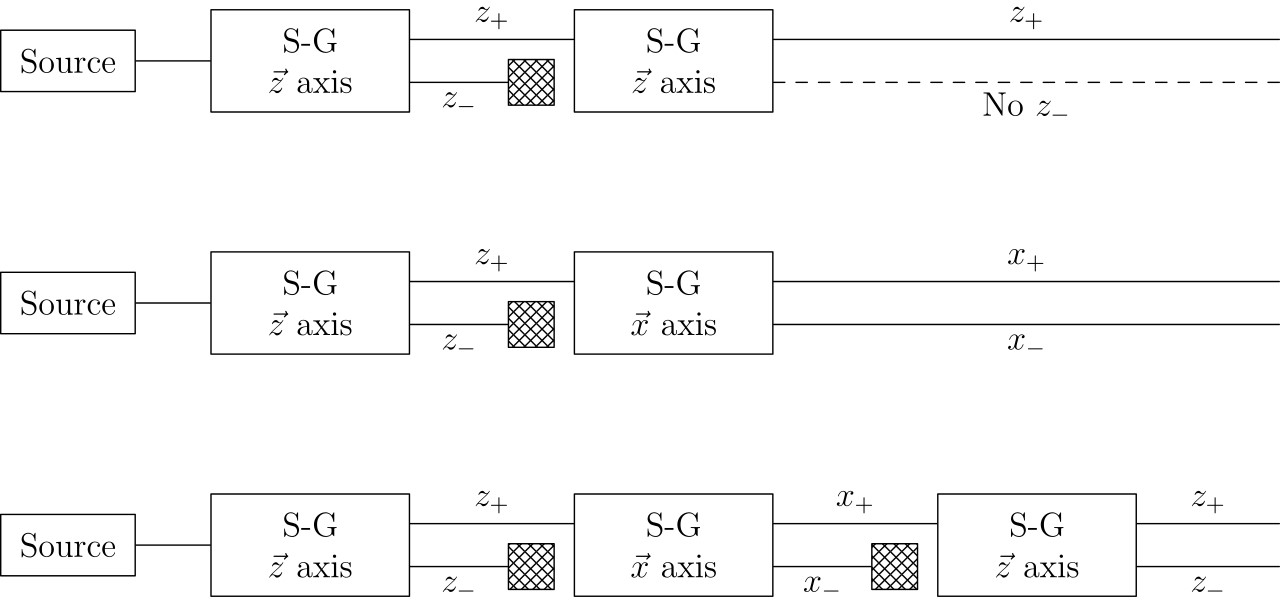

However, you can pass this particle through a magnetic field. If the field is aligned with the z-axis (using x, y, and z to represent our three spatial dimensions), some of the electrons will deflect in the positive direction (corresponding to +½) and others will deflect in the negative (corresponding to the -½) direction.

Now, what happens if you pass the electrons that deflected positively through another magnetic field? Well, if that field is:

- in the x-direction, the electrons will split again, some in the +½ (x-)direction and others in the -½ direction;

- in the y-direction, the electrons will deflect again, some in the +½ (y-)direction and others in the -½ direction;

- in the z-direction, there is no additional splitting; all the electrons are +½ (in the z-direction).

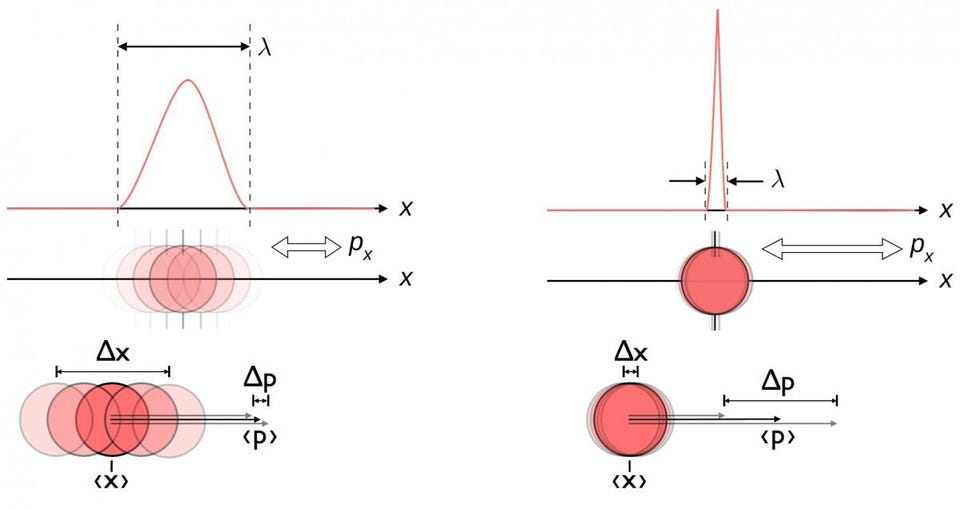

In other words, every individual electron has a finite probability of having its spin be either +½ or -½, and that making a measurement in one particular direction (x, y, or z) determines the electron’s angular momentum properties in that one dimension while simultaneously destroying any information about the other two directions.

This might sound counterintuitive, but it’s not only a property inherent to the quantum Universe, it’s also a property shared by any physical theory that obeys a specific mathematical structure: non-commutativity. (I.e., a * b ≠ b * a.) The three directions of angular momentum don’t commute with one another. Energy and time don’t commute, leading to inherent uncertainties in the masses of short-lived particles. And position and momentum don’t commute either, meaning you cannot measure both where a particle is and how fast it’s moving simultaneously to arbitrary accuracy.

These facts are weird, but they’re not the only weird behavior of quantum mechanics. Many other experimental setups lead to counterintuitively weird results, as in the case of Schrödinger’s cat. Place a cat into a sealed box with poisoned food and a radioactive atom. If the atom decays, the food is released and the cat will eat it and die. If the atom doesn’t decay, the cat cannot get the poisoned food, and remains alive.

You wait exactly one half-life of this atom, where it has a 50/50 shot of either decaying or remaining in its initial state. You open the box. Just before you make the measurement or observation, is the cat dead or alive? According to the rules of quantum mechanics, you cannot know the outcome before making the observation. There is a 50% chance of a dead cat and a 50% chance of an alive cat, and only by opening the box can you know the answer for certain.

For generations, this puzzle has stymied almost everyone who’s tried to make sense of it. Somehow, it seems like the outcome of a scientific experiment is fundamentally tied to whether we make a specific measurement or not. This has been called “the measurement problem” in quantum physics, and has been the subject of many essays, opinions, interpretations, and declarations from physicists and laypersons alike.

It seems only natural to ask what seems like a more fundamental question: what is really going on, objectively, behind-the-scenes, to explain what we observe in an observer-independent fashion?

This is a question many have asked over the past 90 years (or so), attempting to obtain a deeper view of what’s truly real. But despite many books and op-eds on the subject, from Lee Smolin to Sean Carroll to Adam Becker to Anil Ananthaswamy to many others, this might not even be a good question.

Smolin himself put it very bluntly during a public lecture he delivered in 2019, a stance he reiterated in an interview with me last year:

“A complete description should tell us what is happening in each individual process, independent of our knowledge, beliefs, or our interventions or interactions with the system.”

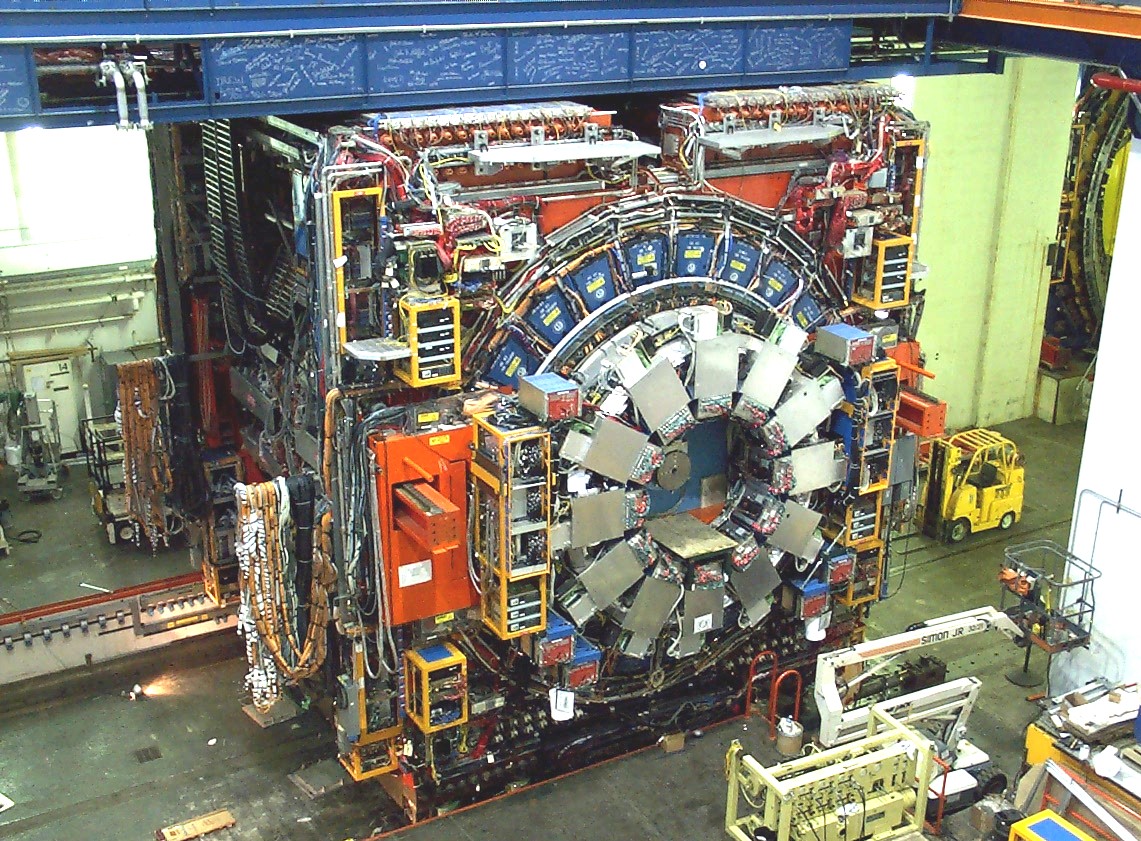

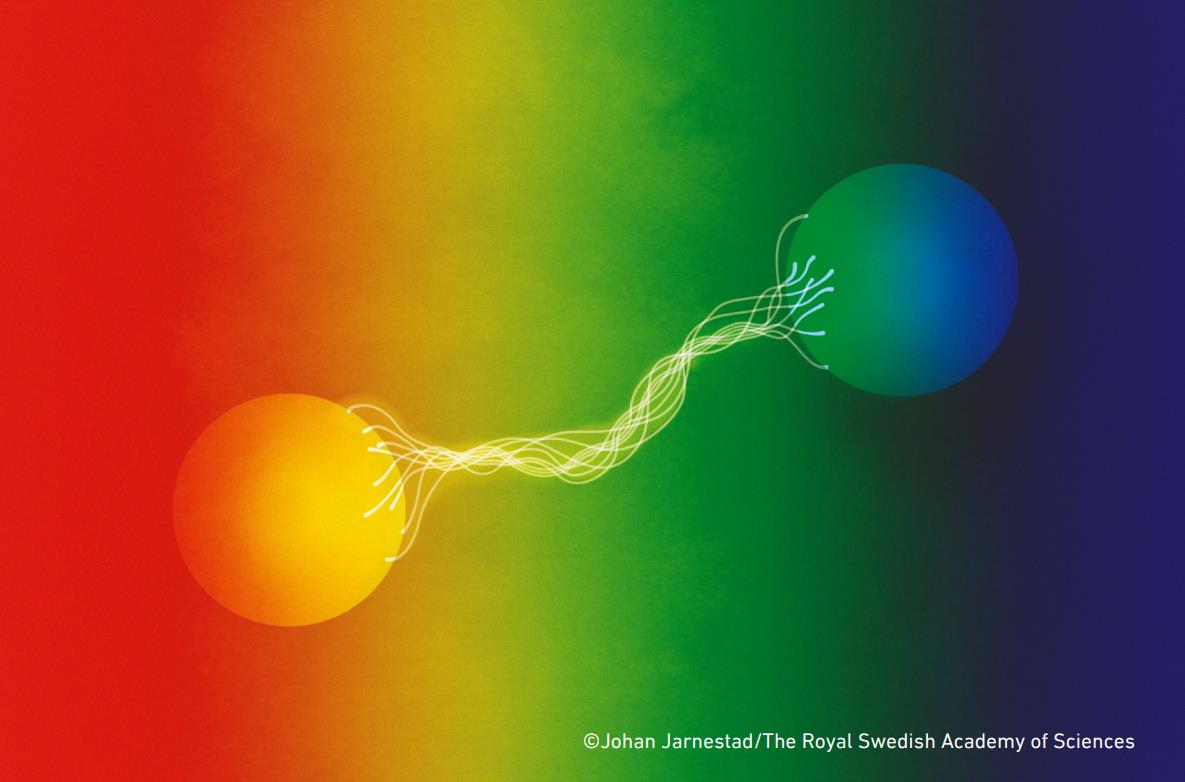

In science, this is what we call an assumption, a postulate, or an assertion. It sounds compelling, but it might not be true. The search for “a complete description” in this fashion assumes that nature can be described in an observer-independent or interaction-independent fashion, and this may not be the case. It’s easy to make an argument that physicists should care more about (and spend more time and energy studying) these quantum foundations, particularly in light of the fact that the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics was just awarded for it.

But pinning down the behavior of nature under all sorts of circumstances is very different than assuming there even is some sort of objective reality that exists, deterministically, independent of any observer or key interaction.

Reality, if you want to call it that, isn’t some objective existence that goes beyond what’s measurable or observable. In physics, as I’ve written before, describing what is observable and measurable in the most complete and accurate way possible is our loftiest aspiration. By devising a theory where quantum operators act on quantum wavefunctions, we gained the ability to accurately compute the probability distribution of whatever outcomes might possibly occur.

For most physicists, this is enough. But you can impose a set of assumptions atop these equations, and come up with a set of different interpretations of quantum mechanics:

- Is the quantum wavefunction defining these particles physically meaningless, until the moment you make a measurement? (Copenhagen interpretation.)

- Do all possible outcomes actually occur, requiring an infinite number of parallel Universes? (Many-worlds interpretation.)

- Can you imagine reality as an infinite number of identically prepared systems, and the act of measurement as the act of choosing which one represents our reality? (Ensemble interpretation.)

- Or do particles always exist as absolutes, with real and unambiguous positions, where deterministic “pilot waves” guide them in a non-local manner? (de Broglie-Bohm/Pilot wave interpretation.)

Sean Carroll has just devised a sort-of-new interpretation himself, which is arguably just as interesting as (or no more interesting than) any of the others. And oh, are there others.

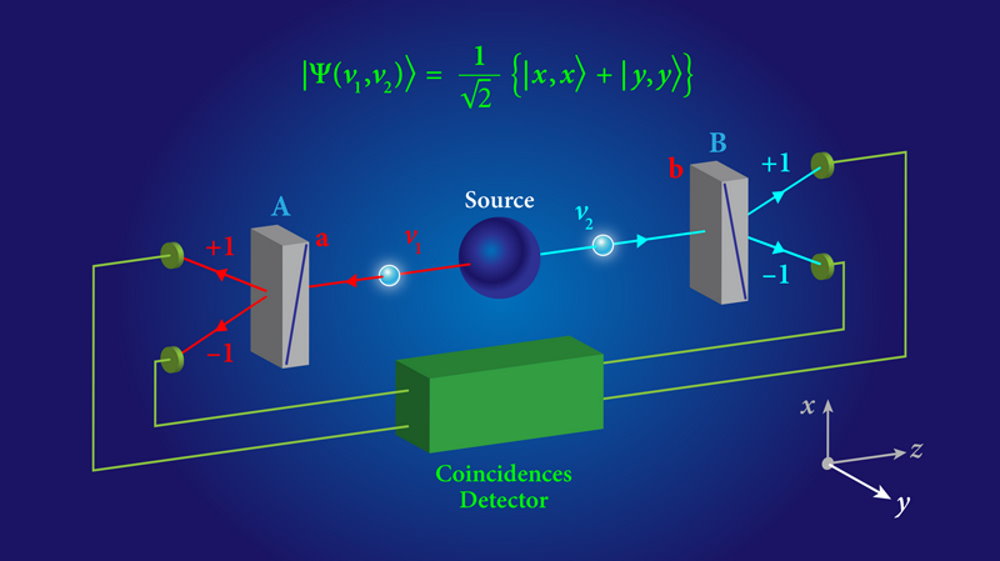

Frustratingly, all of these interpretations, plus others, are experimentally indistinguishable from one another. There is no experiment we have yet been able to design or perform that discerns one of these interpretations from another, and therefore they are physically identical. The idea that there is a fundamental, objective, observer-independent reality is an assumption with no evidence behind it, just thousands upon thousands of years of our intuition telling us “It should be so.”

But science does not exist to show that reality conforms to our biases and prejudices and opinions; it seeks to uncover the nature of reality irrespective of our biases. If we really want to understand quantum mechanics, the goal should be more about letting go of our biases and embracing, without additional assumptions, what the Universe tells us about itself.

Understanding the Universe isn’t about revealing a true reality, divorced from observers, measurements, and interactions. The Universe could exist in such a fashion where that’s a valid approach, but it could equally be the case that reality is inextricably interwoven with the act of measurement, observation, and interaction at a fundamental level.

The key, if you want to further your understanding of the Universe, is to find an experimental test that will discern one interpretation from another, thereby either ruling it out or elevating it above the others. Thus far, only interpretations that demand local realism (with some level of determinism thrown in there) have been ruled out, while the remainder are all untested; choosing between them is exclusively a matter of aesthetics.

In science, it is not up to us to declare what reality is and then contort our observations and measurements to conform to our assumptions. Instead, the theories and models that enable us to predict what we’ll observe and/or measure to the greatest accuracy, with the greatest predictive power, and zero unnecessary assumptions, are the ones that survive. It’s not a problem for physics that reality looks puzzling and bizarre; it’s only a problem if you demand that the Universe deliver something beyond what reality provides.

There is a strange and wonderful reality out there, but until we devise an experiment that teaches us more than we presently know, it’s better to embrace reality as we can measure it than to impose an additional structure driven by our own biases. Until we do that, we’re superficially philosophizing about a matter where scientific intervention is required. Until we devise that key experiment, we’ll all remain in the dark.