Bacteria Can Collectively Resist Antibiotics Study Finds

Outlining the serious threat of antimicrobial resistance, a 2014 World Health Organization report states that “a post-antibiotic era – in which common infections and minor injuries can kill – far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st Century.” New findings on antibiotic resistance complicate the issue further.

A team of microbiologists from the University of Groningen have just published a study in which they reveal that the structure of bacterial communities can provide protection for non-antibiotic resistant members. This means that even without inherited antibiotic resistance, genetically susceptible bacteria can survive and even outgrow their resistant counterparts during antibiotic therapy.

The study found that collective resistance develops as certain resistant bacteria take up the antibiotic and deactivate it. As the concentration of the antibiotic drops below a critical level, passive resistance is provided for all bacteria in the environment.

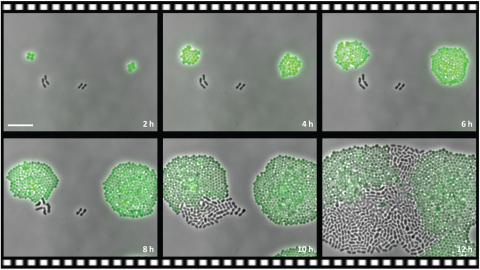

A video from the experiment shows two types of bacteria – one with an antibiotic resistance gene (Staphylococci bacteria) and one without the resistance gene (Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria) – put together in an antibiotic medium (chloramphenicol). While at first only the resistant bacteria grows and divides, after time the non-resistant starts to divide as well, eventually even outgrowing the resistant one.

The scientists hope to draw attention to less studied areas of antibiotic resistance, namely how the microbial context during infection is a potential complicating factor to antibiotic treatment outcomes.

Photo: PLOS