Knowingly Taking a Placebo Still Reduces Pain, Studies Find

Imagine going to the doctor complaining of pain. The physician writes you a prescription. But instead of medication, you knowingly receive a placebo. How would you feel? This is a vitally important question, as the US is going through a chronic pain epidemic right now, with 100 million adults feeling significant pain on a consistent basis. As a consequence, we have the opioid epidemic.

A lot of patients in pain develop a tolerance to opioid pain relievers too quickly, and begin taking more than prescribed to kill bleed-through pain. But the relief only lasts for a time, causing a vicious cycle, forcing the patient to take more, and pushing them ever closer to addiction and overdose. Unfortunately, there are few long-term options, besides alternative medicine, when it comes to chronic pain. Now, imagine receiving effective pain relief without the risk of addiction, overdose, or even side effects?

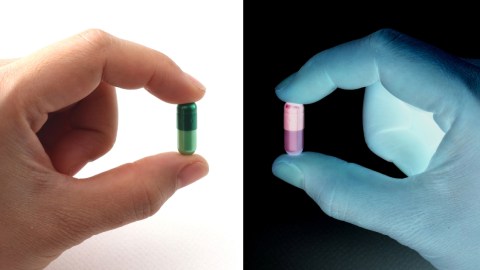

One way to do that might be to instigate the placebo effect. Usually, we think of a placebo as a “fake” pill, sometimes called a sugar pill. They’re used in clinical trials, made to look just like the medication they are mimicking, but without any active ingredients. Researchers in two important studies found the results of using the placebo effect for medical aims was anything but fake. Today, knowledge of the effect is widespread. It’s so much a part of our consciousness that Harvard University researchers found that knowingly giving patients a placebo reduced their pain.

All medications come with the risk of side effects. What if we could induce the placebo effect for symptom relief?

Though we’ve known about the placebo effect for a long time, medical science still doesn’t know exactly how it works. In this study, researchers at Harvard Medical School wanted to know what impact, if any, the placebo effect would have, if participants knew up-front they were getting one. Dr. Ted J. Kaptchuk led the study on what are being called “open-label placebos.”

Professor Kaptchuk is the director of the Harvard-wide Program in Placebo Studies and the Therapeutic Encounter (PiPS) at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He’s been studying the placebo effect for over 20 years. In one of his previous studies, he and colleagues recruited irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients. Each suffered from abdominal cramps, and either constipation or diarrhea. Half of participants received an “open-label” placebo. The other got no medical intervention. Those who received a sugar pill saw their symptoms improve dramatically.

In a second and more recent study, Prof. Kaptchuk looked at using the placebo effect to treat lower back pain, something every adult in the world will confront at one time or another. Globally, chronic lower back pain is the number one cause for disability. He and colleagues concluded that those patients who took a placebo knowingly, in addition to a traditional pain reliever, experienced more pain relief than those who took medication alone.

“This new research demonstrates that the placebo effect is not necessarily elicited by patients’ conscious expectation that they are getting an active medicine, as long thought,” the researcher said. “Taking a pill in the context of a patient-clinician relationship — even if you know it’s a placebo — is a ritual that changes symptoms and probably activates regions of the brain that modulate symptoms.”

The ritual and expectations surrounding medical care may engage the brain in a way that can bring us relief.

97 patients with chronic lower back pain took part. Each was then given a one-on-one, 15-minute session outlining the placebo effect. Then, they were put randomly into one of two groups. The first received the usual treatment, while the second also received an open-label placebo. 85-88% of patients were already on pain medication. None were taking opioids. They were on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) such as ibuprofen (Advil, Bayer), aspirin, or acetaminophen (Tylenol).

Those taking these drugs could continue to do so, but weren’t allowed to take part in any dramatic lifestyle changes. After three weeks, those in the placebo group reported a 9% reduction in usual pain, a 16% reduction in maximum pain, and a 29% reduction in disability related to pain. Kaptchuk said the body responds to the rituals we associate with medical care. But how did the patients feel about knowingly taking a placebo? Lead author on this study, Claudia Carvalho, PhD, said that rather than feeling lied to, the patients felt empowered, as they felt like they were taking part in a cutting-edge approach.

Kaptchuk says that placebos can’t replace every medication. It can help with symptom control for things like nausea, pain, or fatigue. But it won’t help with cancer, atherosclerosis (clogged arteries), or high cholesterol, among other maladies. More studies are being conducted by Kaptchuk to help us further understand how the placebo effect might be used in palliative care—to treat symptoms.

Kaptchuk said, “Our hope is that in conditions where the open-label placebo might be valuable, instead of putting people on drugs immediately — for depression, chronic pain, fatigue — that people would be put on placebo.” He added, “If it works, great. If not, then go on to drugs.”

To learn about the genetic component of the placebo effect, click here: