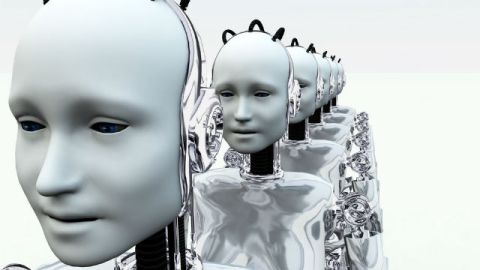

Are We Teaching Citizens or Automatons?

Since the standards-based model of education overtook American public schools a generation ago, the answer to this question has been simple: prepare students for college and get them ready to be productive participants in the workforce. The new Common Core Standards Initiative— already adopted by 46 states and the District of Columbia to guide curricula in their public schools — is no exception:

The standards are designed to be robust and relevant to the real world, reflecting the knowledge and skills that our young people need for success in college and careers. With American students fully prepared for the future, our communities will be best positioned to compete successfully in the global economy.

College and careers. Careers and college. The Common Core communicates its consequentialist mission consistently throughout its materials, and, truth be told, there is something to admire in its standards’ relatively open approach in contrast to the byzantine pedagogical straight jackets they are replacing. The new standards constitute a well-intended attempt to address an inequity-laden public educational system. They seem to stem from sound, research-based analyses of what it takes to build academic skills in young people.

There are a couple of “c”s missing, however, and their absence brings me, as an educator, some discontent. Of course we want to prepare our children for college and we want to give them tools for successful careers. But it isn’t clear that the Common Core is adequately ambitious or forward thinking, and there is little in the standards to prepare students for citizenship, for creative interactions with ideas, or for contemplating the conundrums of life in the 21st century.

To be fair, when I say little, I don’t mean nothing. The English Language Arts standards, for example, cite works by Thoreau, Paine, and Orwell as examples of 11th and 12th grade texts. That’s encouraging. And they prescribe student debates and discussions under the “Speaking and Listening” standards. More good news. That said, though, the Common Core puts an orientation toward good citizenship and life-navigation skills on the rear burner, well behind lessons preparing students for assessments testing discrete, discipline-based skills.

What is the impact of the standards movement on the soul of the learner? A friend of mine who teaches art at an elementary school in Brooklyn has noticed her students request permission and seek validation before making any move. Here is what she told me:

They’re always asking every step of the way if what they’re doing is OK. “Can my dog have two legs?” “Could I paint a panda that is purple?” Of course you can! They’re so trained to think that there is only one right answer. I have to tell them it would be very uninteresting to me if you all made the exact same thing.

Old school public education reformers put creativity, citizenship and habits of social interaction front and center. For John Dewey, “the development within the young of the attitudes and dispositions necessary to the continuous and progressive life of a society cannot take place by direct conveyance of beliefs, emotions, and knowledge.” Fostering the skills of young citizens in a democracy doesn’t happen by accident. This process, Dewey writes in Democracy and Education (1916),

takes place through the intermediary of the environment…It is truly educative in its effect in the degree in which an individual shares or participates in some conjoint activity. By doing his share in the associated activity, the individual appropriates the purpose which actuates it, becomes familiar with its methods and subject matters, acquires needed skill, and is saturated with its emotional spirit.

This spirit is what I find to be missing from the Common Core, and what makes me melancholy about the whole enterprise. With its individualistic emphasis and results-oriented approach, students will work their way from Kindergarten through high school graduation with plenty of practice finding evidence in “information-based texts,” and preparing for standardized assessments (still in the works) to identify which students are learning and which teachers are teaching. But I worry the rising generations will have precious little experience creating knowledge in concert with others in creative and interactive projects, testing their intuitions against challenging new theories, exploring the peripheries rather than just the core. I worry they won’t have much fun. I worry they won’t have fully developed civic tools and temperaments to interact productively and meaningfully with others once they have won those coveted spots in colleges and careers.

Nothing in the new standards precludes, exactly, the richer, deeper, more interactive and more progressive teaching techniques and curricula that many educators favor. But with data-driven teacher evaluations forming the basis of the recent push for greater corporate-style accountability, it is easy to predict how this will go. More time and energy devoted to test prep, less and less to cultivating the emotional spirit that comes when students are actively engaged in communities of inquiry. “A progressive society counts individual variations as precious,” Dewey writes, “since it finds in them the means of its own growth. Hence a democratic society must, in consistency with its ideal, allow for intellectual freedom and the play of diverse gifts and interests in its educational measures.”

Those gifts and interests bring more benefits: intellectual resources to help navigate life’s difficult moments. In an amiable ramble in the Stone earlier this month, “Stormy Weather: Blues in Winter,” Avital Ronnell presents a lovely response to her friends who “used to say to me that it was the study itself of philosophy that brought me down”:

[U]pon reflection, I have to think it’s the other way round. I consider philosophy my survival kit. In any case philosophy does the groundwork and comes face to face with my basic repertory of distress: forlornness, the shakes, and other signs of world-weary discomfort.

One shouldn’t have to have Jacques Derrida as a teacher (as Ronnell did) to develop a minimal survival kit to navigate life’s inevitable complexities, disappointments and crises. This too, along with a full-bodied civic education, belongs in the core. As long as our public schools see children only as pre-collegiate, proto-capitalist participants in the global economy, there is little hope the Common Core will have much to say about the core problems of human existence.

Image credit: Shutterstock.com

Related Content

Testing, K…1…2…3…: Parents’ Options in the Age of the Bubble Sheet

Holding Their Tongues? Public Employees’ Rights and the Testing Debate

Love in the Schoolyard: A Flash Mob in Brooklyn