Earth’s magnetic field supports biblical stories of destruction of ancient cities

- The Earth’s magnetic field is far from constant. We can track its shifts in rocks that melt and then resolidify.

- Archaeological finds containing once-burned rocks can be precisely dated using this method.

- By utilizing the ancient orientation of the Earth’s magnetic field, scientists have been able to piece together the history of military conquests in ancient Judea.

A vast city of 10,000 once stood within the grounds of Tel Zafit National Park. Now it is an archaeological dig, nothing but burned mud bricks, a crumbling break in the city’s defenses, and weapons cobbled together at the last minute from animal bones. What happened here? What force brought this great city to its end?

According to the Bible, Gath was one of the main Philistine cities and the home of Goliath the Giant. Its destruction is glossed over, described in less than one verse of the Bible, in the book of 2 Kings.

Archaeologists have long worked to figure out what happened to the ancient city of Gath, and just as important, when it happened. But dating sites like this is no straightforward task. Recently, a team of scientists led by Yoav Vaknin of Tel Aviv University tried a new method to date archaeological digs like Gath: They used the Earth’s magnetic field. Their results recently appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Pole reversal

Deep within the Earth, thousands of miles below the crust, lies the boundary between the planet’s solid inner core and the molten outer core that surrounds it. That boundary burns at 6,000° C, hotter than the surface of the Sun. It is the hottest place on Earth.

In the outer core, massive currents of molten iron convect in giant cells around the inner core. Imagine water boiling on your stove — only on a much larger scale, and warmed by superheated liquid rock. This rock is made up of iron and nickel, and its motion creates the Earth’s protective magnetic field.

We can thank that magnetic field for a lot of things, including life. It helps shield the Earth, deflecting radiation up and around the planet. It protects our planet from solar winds and coronal mass ejections from our sun, as well as from cosmic rays.

But since motion within the core is chaotic, the magnetic field is dynamic, too. In fact, the magnetic field of the Earth completely reverses — the North and South take turns being the pole of attraction. Sometimes the switch happens after tens of thousands of years, sometimes after tens of millions, but even when it is not reversing, the magnetic field of the Earth is constantly in flux. The North Pole travels about 45 km per year, its intensity gradually varying.

The history of changes in the magnetic field is recorded in rock. Perhaps the most well-known record is etched in stone at the mid-Atlantic ridge. Here, new seafloor is constantly being created as the tectonic plates spread along fault lines as long as the ocean. As these molten rocks orient themselves, cool, and solidify, they record the direction and intensity of the magnetic field. A search of the seafloor allows us to read the history of the Earth’s magnetic field itself.

Surprisingly, this method can also be used for archaeological sites like the one at Gath. If rocks at these sites become hot enough, they too can align to show the intensity and direction of the magnetic field. Such heat can be generated during military actions, when widespread destruction is common.

A magnetic history of biblical brutality

If you were an Israelite around 2,800 years ago, the name Hazael probably struck fear into your heart. In the book of 2 Kings, city after city falls to King Hazael. This ruler of Damascus leveled many cities in Judah and Israel. The prophet Elisha addresses Hazael in 2 Kings 8:12:

“‘Why does my lord weep?’ asked Hazael. ‘Because I know,’ he [Elisha] replied, ‘what harm you will do to the Israelite people: You will set their fortresses on fire, put their young men to the sword, dash their little ones in pieces, and rip open their pregnant women.’”

Many archaeological sites illustrate the brutality of Hazael’s campaigns. They tell the stories of how entire cities were destroyed, and Gath was one of these. Massive destruction is evident at the site, showing a long siege trench, fallen buildings, and human remains.

Different approaches to date these sites lead to different conclusions. But one element in the destruction of these cities could help researchers. The battles were extensive and terrible, with widespread fires blazing at over 600° C. This heat baked the mud bricks in the cities, and aligned them with the Earth’s magnetic field.

Vaknin and his team realized this, and they knew something else about the Earth during this time. While the magnetic field is continually changing, there are periods during which it fluctuates more quickly. This period was one of them, with fluctuations measuring twice as strong as their current propensity. “The dating resolution depends on the rapid fluctuations, so I am lucky to work on this period,” Vaknin told Big Think.

In short, the scattered fragments of ruins held the information researchers needed to determine exactly when these cities were destroyed.

Anchoring results in time

To use this data, the team gathered the information the mud bricks held about the direction and intensity of the Earth’s magnetic field, and they combined it with knowledge of other events whose timing is precisely known. These events are known as chronological anchors, and unfortunately, Vaknin says, they are rare.

“The 701 [BCE] Assyrian campaign is my favorite example,” Vaknin says. “When the historical sources and the archaeological record match (more than 1000 arrowheads found in the destruction of Lachish, for example) — Bingo! We have an anchor.

“We then compare the magnetic results from these anchors to those from other finds whose dates that are not as well known but are roughly dated to the same periods, according to other dating methods.”

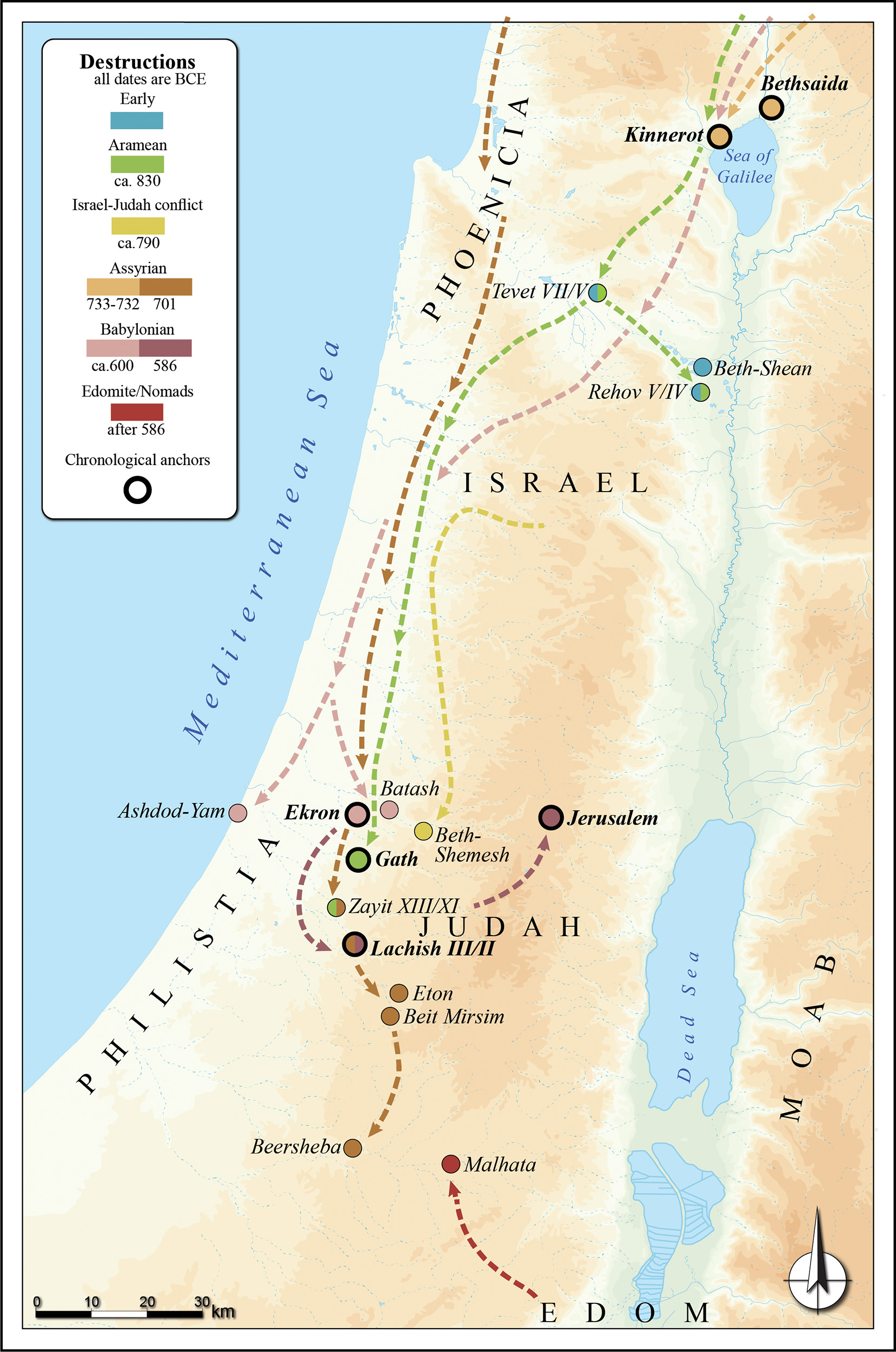

Using their chronological anchors, they could create a timeline. They recorded the intensity and direction shown in mud bricks from 21 archaeological layers at 17 sites to discover exactly when each of these cities was destroyed. The team showed that several cities were destroyed around the same time — Tel Rehov, Horvat Tevet, Tel Zayit, and Gath. They suggest that all of these cities were destroyed by Hazael.

The timing of the destruction of another city, Tel Beth-Shean, is often contested. Vaknin’s team studied this site and found that its bricks recorded a different magnetic field intensity and orientation than the other cities, suggesting that this Judean city was destroyed perhaps 70 to 100 years earlier, by Pharaoh Shoshenq I. The biblical account of still another ancient city, Tel Beth-Shemesh, suggests destruction at the hands of Jehoash, the King of Israel, and the team’s geomagnetic dating showed a timeline consistent with this interpretation. They also found that the Babylonian conquest of Judea was likely focused on Jerusalem.

Piece by piece, the destruction of other sites has come into focus — some were leveled by the Babylonians, others by the Assyrians. Their method has allowed the team to trace the contours of the region’s chronology, suggesting the timeline of the falls of various parts of Judah and Jerusalem.

Especially in this part of the world and for this period of ancient history, geomagnetic dating is more precise than radiocarbon dating. This is thanks to the number of archaeological sites paired with the swiftness and strength shifts in the magnetic field. But the method can be used anywhere rocks were heated enough to align with the Earth’s magnetic field.