The 13th-century nun whose heart was dissected in search of a crucifix

In an abbey in a small Italian town, a fresco shows a haggard Christ shoving the end of his cross into a woman’s chest. Perhaps half the cross has been mysteriously absorbed into her body; she calmly gazes upward, guiding it inward with gentle hands. This is Saint Clare (Santa Chiara) of Montefalco, abbess in the late thirteenth century. The painting depicts a vision she had, one she recounted so often that, upon her death, her fellow nuns decided to actually cut open her heart in search of the cross of which she had spoken so frequently.

This dissection represents an early entry in what would become a tradition of performing autopsies to consider an individual’s sanctity, according to historian Simon Ditchfield. The stones formed inside organs, revealed after death, served as “potential markers of sanctity in early modern Italy,” explains historian Jetze Touber.

Inside Clare, examiners found not only a tiny crucifix, but an array of the instruments of the passion: “a shroud, a crown of thorns, three nails, a lance, a sponge, a whip and a column,” all formed out of the flesh of her heart. On top of that, three stones were discovered in her gallbladder. According to Isidoro Mosonio, then Vicar General of Bologna, the stones were

colored like ashes, equal in appearance, color, and weight, and laid out in the gallbladder in such a way that a triangular form resulted, by which the secrets of the Very Holy Trinity were represented.

At least, that’s the story told at Clare’s canonization trial, a few years after her death. The case was controversial, notes historian of religion and science Bradford Bouley. The nuns were suspected of planting the relics, and it was rumored that in life, Clare had consorted with heretics. Although the nuns were ultimately judged innocent of subterfuge, Clare would not be officially declared a saint until centuries later.

Saint Clare was not the only holy woman whose innards were ransacked for hidden symbols of saintliness. Saint Margarita of Città di Castello similarly was discovered to have three stones in her heart, each ornamented with scenes, “representing the birth of Christ, the Virgin Mary, Joseph and a white dove.”

As historian of science Katharine Park writes, even before the examination of Clare, it was thought that

the saint’s body differed from that of other people, in the way that the victim of plague or poisoning was recognizable by certain unmistakable signs. These differences were not confined to incorruptibility and the odor of sanctity but also included external and internal marks, such as stigmata and the alien structures found in Chiara’s and Margarita’s hearts.

Conversely, a criminal’s body might contain indications of a malevolent nature—like a hairy heart or a mysterious extra rib. In sin, as in sanctity, the physical and spiritual were deeply intertwined.

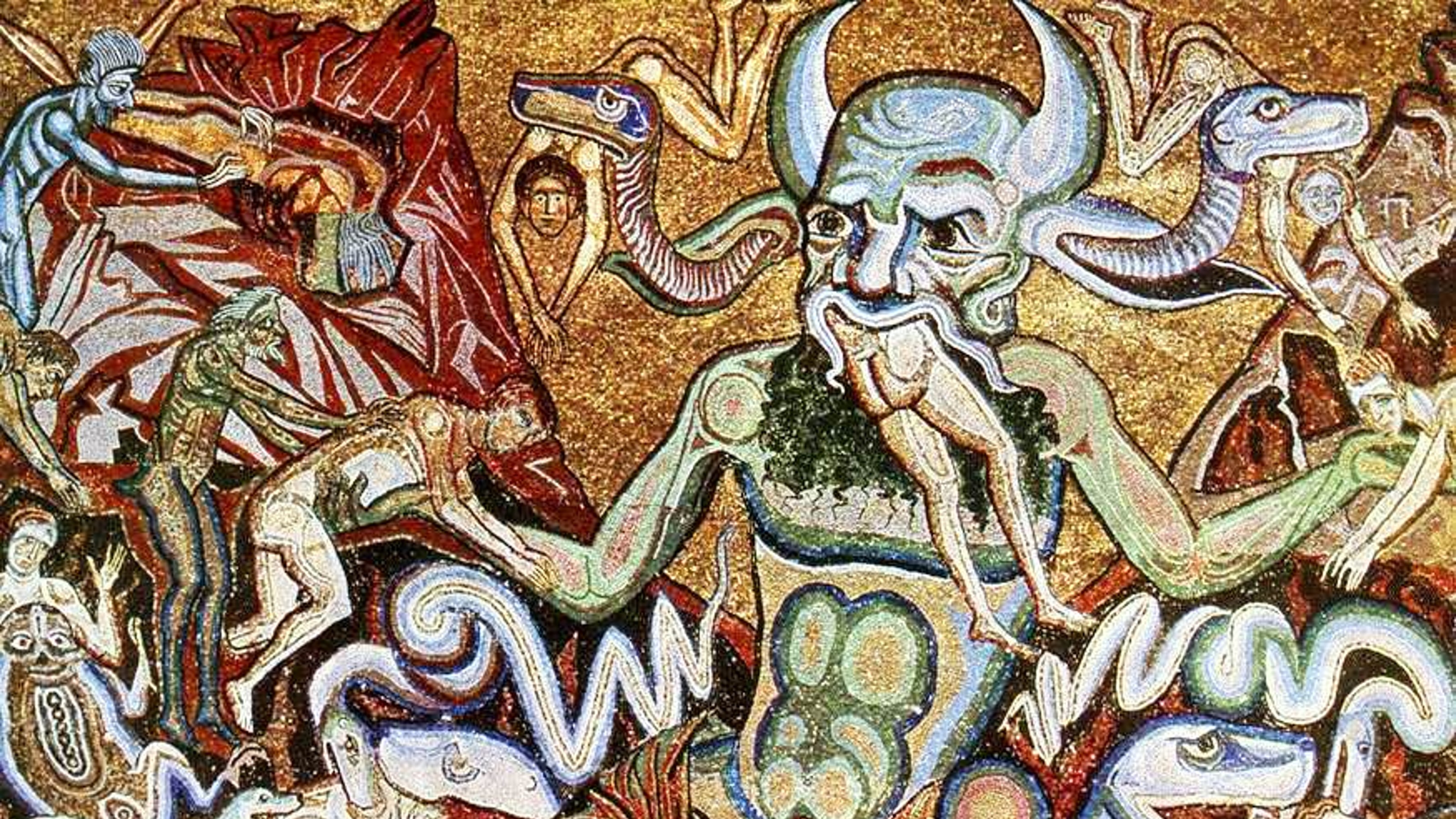

Similarly, there was a mysterious correspondence between the presence of the divine and the presence of the demonic. The signs of possession were strangely similar to the signs of holiness: possessed people and holy people both were known to go into trances, to levitate, to have a mysterious grasp of foreign languages, to utter strange prophecies, and to survive long periods without eating. As Nancy Caciola and Moshe Sluhovsky describe, treatises on witchcraft warned of “a demonic hierarchy of ‘anti-saints’ modeled on the divine” and characterized by “anti-miracles.” The holy spirit, like evil spirits, could inhabit the body; but while the divine would make itself known inside the heart, demons were obliged to lurk in the digestive system. And women, believed to be more physically porous than men, were held to be correspondingly more liable to be possessed.

At the same time, the culture of piety among female mystics was shockingly, even graphically visceral, notes historian Susan Juster. Blood poured from the mouths and nostrils of religious women, and their bodies contorted as they were carried away by mystical visions. Frenzies of ecstasy and torments of suffering mingled together, merging into a single holy fervor.

Church authorities tended towards suspicion: was a given holy woman a vessel of the divine, as she claimed to be, or were her seeming visions simply a reflection of some kind of pathology—a demon, a disease? As Caciola and Sluhovsky argue, this attitude was a common—and growing one—in the Middle Ages. Though it was a time marked with “the rise of the female saint,” that rise

was neither linear nor uncontested. Indeed, at the same moment that more and more women began to gain attention for their claims to celestial visions, suspicions concerning women’s reliability when describing their supernatural experiences grew.

At the same time, write Caciola and Sluhovsky, “there also was a sharp increase in reports of women being defined as demoniacs—that is, as possessed by demons.” In the historical record, they note, the difference between a report of a twisted demoniac and a hagiography of a blessed saint could be simply a matter of who’s telling the story.

Perhaps the future St. Clare’s sisters were aware of the fine line walked by their abbess, and that’s why they felt so strongly about proving that she had consorted with the holy spirit. Their convictions were firm enough that they were willing to slice her heart open and take a look inside.

This article appeared on JSTOR Daily, where news meets its scholarly match.