Homicidal mice and 4 other strange origin stories of royal families

- Myths often walk a line between religion, entertainment, and history. The legends we tell often hark back to some distant truth.

- Almost all royal lineages will have a legend about their origin. They are used to legitimize their rule and add authority to their demands.

- Here are five of the most peculiar examples of these stories.

Sociologists and anthropologists often debate to what extent people “actually” believed myths. Did the Vikings genuinely think thunder was caused by Thor? Do the Māori really suppose that the goddess Pani gave birth to the first yam? Do the Choctaw actually believe solar eclipses are caused by a black squirrel? Myths always have walked a line somewhere between religion, history, and entertainment. A great example of this is in the origin stories of royal lineages.

Almost all the pre-modern monarchies of the world have a mythological story at their source. For a few dynasties, these stories are vitally important in establishing legitimacy. For others, they were just a good laugh that no one really took seriously. Most lay in between. Here we have gathered five of the best origin stories.

King Arthur

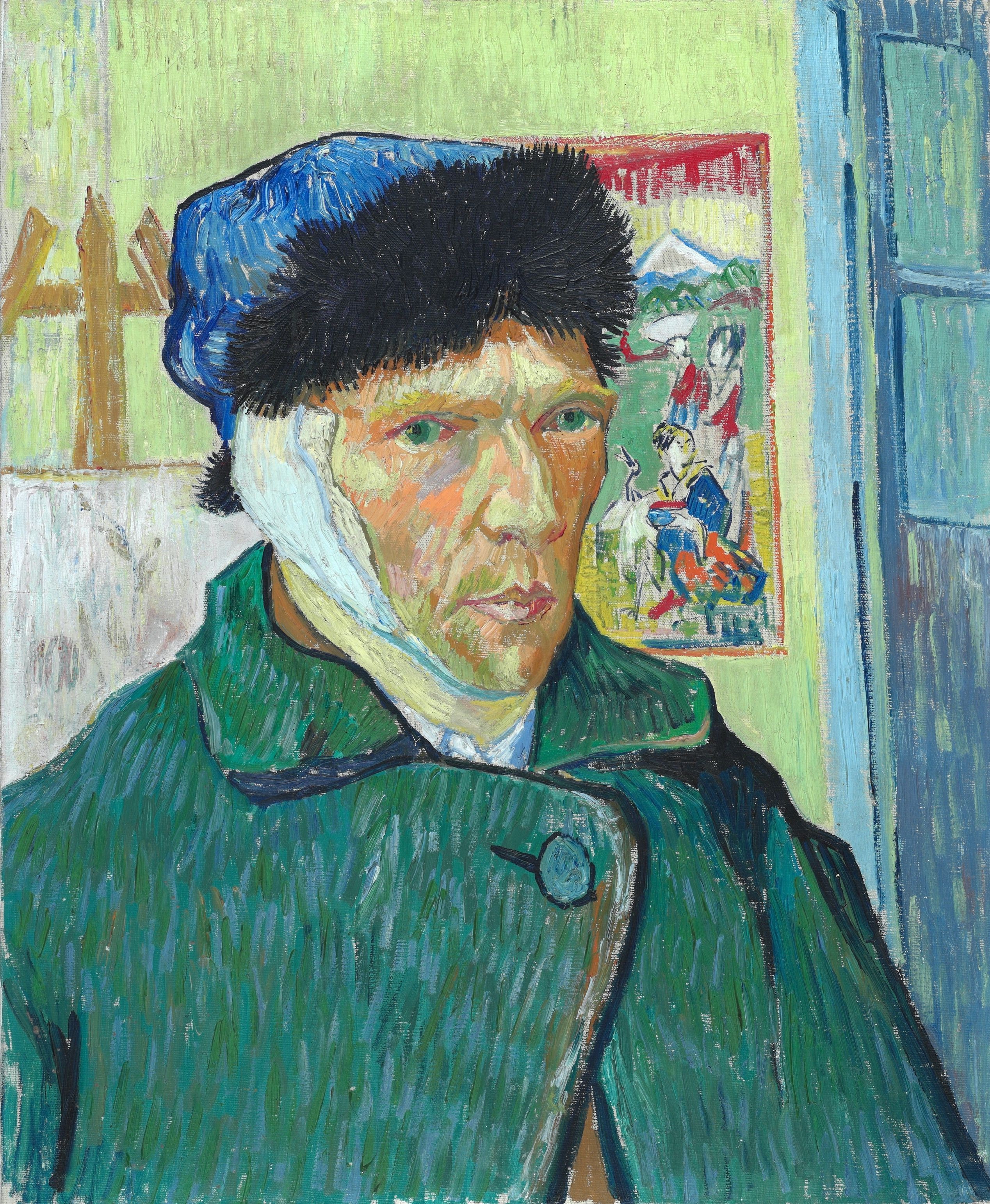

When William the Bastard, a Norman, marched his victorious and blood-splattered army through the streets of Winchester, he knew that he had a problem on his hands: One does not simply take the English throne. It wasn’t enough to stab and trample anyone stupid enough to stand in front of an armored cavalry charge; you had to prove you were the real deal. So, the first thing needed was a name change: “Guys, call me William the Conqueror,” he said, and everyone nodded. “Oh, and tell everyone I’m the great-great-grandson of that Arthur bloke.”

Most English monarchs since William have claimed to be descended from King Arthur. The Normans were French and had good reason to be worried about the Anglo-Saxons not taking their rule kindly. The story of King Arthur, though, was as Briton as Briton can be (never mind that most other European nations claimed him, as well). So, it was a great PR stunt on behalf of the Norman kings to tell everyone that they were the true Britons. They were Arthur’s children, returned to their rightful place. “We’re not invaders,” they said, “but your saviors.”

The mouse tower and the wheelwright

Popiel was the ruler of Poland. He had a lovely castle overlooking Lake Gopło, and he married a German princess who was famed for her beauty. Unfortunately for everyone, though, Popiel was an utter git. He was cruel, greedy, and unjust. He poisoned an entire council of the tribes’ elders and murdered the sons from his previous marriage.

Everyone was fed up with him. But what could they do? Popiel had surrounded himself with square-jawed mercenary henchmen. He was holed up in a fortress that touched the sky. So, the people had only one hope: the Holy Mice of Kruszwica. They prayed to the Slavic gods, and the gods sent them help. Hordes of mice, with huge teeth and a penchant for blood, stormed Popiel’s castle. His guards tried desperately to kill them, but from every cut, another regicidal mouse spawned. The mice chomped through the castle walls, found Popiel on his throne, and gave him his long overdue, rodent-style justice.

Meanwhile, down the road, the poor, gentle, and all-round good egg, Piast the Wheelwright, was busy wrighting wheels. One day, two wizards in disguise asked for his hospitality and Piast, although humble, gave as much as he could. Miraculously, his cellars and his house overflowed with plenty — wine, bread, and gold. So blessed by the gods, Piast inherited Popiel’s throne and thus began the Polish royal dynasty.

The dragon rider

The Han ethnic group makes up 92% of all China, which means they make up about one-fifth of the entire world. And they all are said to be descended from the “Yellow Emperor,” Huang-di. Huang-di is the oldest of the legendary Chinese emperors, five rulers who unified China and gave it prosperity, innovation, and (temporary) security.

The Yellow Emperor gave the Chinese medicine and a written language. His wife taught everyone how to weave silk from silkworms. (Silk has been, for millennia, one of China’s key industries.) When Huang-di went touring over his empire, he rode a chariot pulled by dragons and an elephant. Tigers, wolves, phoenixes, and snakes followed behind. When he died, Huang-di turned into a dragon and flew up to the gods — and remains there today, in many places seen as a kind of demi-god.

The sons of Sheba

In 1 Kings chapter 10, we are introduced to the Queen of Sheba. According to this account, she came to visit the wise and brilliant King Solomon at the head of a caravan “with camels that bore spices, very much gold, and precious stones.” In poems, literature, and popular culture, Sheba has now come to describe anything rich or decadent. But where was Sheba? Most likely, in or around Ethiopia. Sheba is usually identified as “Saba,” an empire that ranged from the southern Arabian peninsula to East Africa. This is why Ethiopian dynasties claim to descend from Solomon.

According to a 14th century text, Kebra Negast, Solomon seduced the Queen of Sheba (Makeda), who returned home (to what is modern-day Ethiopia) pregnant with his baby. This child, called Menelik I, eventually would become the first of the Ethiopian royal line. It was even said that Menelik then found and took the Ark of the Covenant (now lost) back to his palace.

For centuries, Ethiopian rulers could say they were of the same line as King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Thus, they were the offspring of wisdom and wealth, combined.

The five-toed chicken

A long time ago, when the wind was young, the world was nothing more than a great ocean. There were no trees, no rocks, and no life — just a great, roiling sea. Then, from out of the heavens, there appeared a long chain. Scaling down this chain, with the skill and alacrity of Tom Cruise, came Oduduwa. Oduduwa held in his celestial backpack three things: a handful of dirt, a palm nut, and a five-toed chicken. He threw the dirt into the ancient waters and put the chicken on the dirt. As it scratched and fidgeted about, the chicken scattered out all the lands of the world. Where the chicken stood — what is now modern-day Nigeria — marked the center of the world.

Oduduwa was supposed to return home to the heavens. Olorun, the great sky god, called him back like a dad at dinner time. But Oduduwa liked the world, and he liked his chicken, so he decided to stay. Oduduwa planted his palm nut which produced a tree of 16 branches, each of which became his sons and grandsons. With divine blood in their veins, Oduduwa and his children became the Yoruba rulers.