7 philosophers who were exiled from their societies

- Many thinkers have been killed for their ideas. Some got away with exile.

- Most of the ones we’ll look at here were driven out by the government, but others fled for their own safety.

- The fact that some of these thinkers are still famous centuries after their exile suggests they might have been on to something, even if their countrymen disagreed.

It’s no secret that people often have a difficult time allowing radical thinkers to live in peace. History is full of examples of philosophers who died for the crime of thinking differently. It is also full of stories of people who were sent packing by the societies they tried to help. Here, we’ll look at seven philosophers who were either forcibly or voluntarily exiled for a variety of reasons. Most of all, they were punished for the crime of thinking.

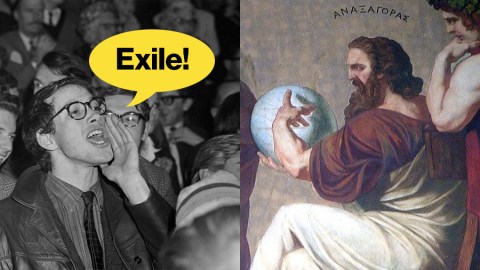

Anaxagoras

A pre-Socratic Greek philosopher, Anaxagoras was driven from Athens for the crime of realizing the moon is made of rock.

A scientifically minded thinker, he spent a great deal of time devising models to explain cosmology. He was one of the first people to understand how the moon reflects light from the sun and how this creates the phases we see in the moon. He was the first to explain solar and lunar eclipses accurately, suggested that the moon has mountains, and argued that the sun was a burning mass “larger than the Peloponnese.”

At the time, these ideas were utterly radical. Many Greek city-states treated the sun and moon as divine entities or gods. He was tried for impiety, as Socrates would later be, and sentenced to death in a trial that was as much concerned with his philosophy as it was with his political circle.

His friend Pericles, the leading citizen of Athens, was able to convince the voters to reduce the penalty down to exile. Anaxagoras moved to Lampsacus in what is now Turkey, where he quietly continued to work.

Diogenes

One of the most brilliant and eccentric philosophers of all time, Diogenes is well remembered for his bizarre lifestyle and educational antics.

Less often recalled is that he got his start in philosophy after being kicked out of his hometown. His father, Hicesias, was a banker, and it is likely that Diogenes was at least somewhat involved in his business. While the details are fuzzy, it appears that they were engaged in a scheme to debase the currency. For this, we have some corroborating archaeological evidence, as a large number of coins from the time in the area around Sinope have been found to be adulterated.

They were caught, and Diogenes was stripped of his citizenship and sent into exile.

After this setback, he moved to Athens. He took a visit to the Oracle at Delphi, who encouraged him to “deface the currency” yet again. However, knowing that the Oracle was famously cryptic, he took the suggestion to mean that he should strive to change accepted norms, customs, and values rather than ruin coins.

He took the message to heart and spent his life living in a barrel, walking backward, begging from statues, and searching for an honest man in the marketplace. The people of the cities he lived in were utterly baffled.

Confucius

The undeniable heavyweight champion of Chinese philosophy, Confucius spent much of his working life in exile.

His career began not in philosophy, but government, where he was a well-known minister to the Duke of Lu. The neighboring state of Qi, fearful at the potential of the reforms Confucius was trying to implement and wary of Lu’s increasing power, sent the Duke of Lu a gift of 100 excellent horses and 80 dancing girls.

He promptly spent most of his time with these gifts and forgot to run the country for a few days.

Confucius, disappointed in the Duke’s behavior, took the next chance to resign, waiting until a good excuse came up so everybody could save face over the incident. He spent the next 13 years on the road visiting the courts of several states and trying to find one which would implement his reforms for good governance. None of them would.

Somewhat discouraged, he returned home where he spent his final years teaching his 70 odd disciples his philosophy. After his death, his disciples collected his works and continued teaching them. In the end, his philosophy would be adopted by several Chinese dynasties and continue to influence Chinese society to this day.

Aristotle

Aristotle is one of the most famous philosophers in world history. He functionally invented logic, wrote on every subject imaginable, and devised a system of ethics that still holds up pretty well. However, his tutoring of and continued association with Alexander the Great would cause him to die in exile.

Aristotle was made the head of the Macedonian Royal Academy by King Phillip II and tutored his son Alexander alongside several others who would later become kings and leading generals of the ancient world. How long this arrangement lasted is a subject of continued debate, but it was at least a few years.

Years later, after Alexander had consolidated his power over Greece, Aristotle moved back to Athens, where he opened his school, taught many students, and wrote some of his most famous works.

After the death of Alexander, there was widespread anti-Macedonian sentiment throughout Greece. In Athens, leading citizens accused Aristotle of “impiety,” one of the crimes that got Socrates the death penalty.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Aristotle declared that Athens “would not sin twice against philosophy” and fled the city. He spent his final year in exile on the island of Euboea at an estate owned by his mother’s family.

Jean Jacques Rousseau

A Swiss philosopher working during the Enlightenment, Rousseau was a well-known radical who was always aware of how close to the line he was playing it. While working in pre-revolutionary France, he often chose to live very near the Swiss border just in case the need to flee came up.

In 1762, his radical ideas caught up with him. He published Emile, or On Education, a book that focused primarily on how to educate children in a way that will not cause their innate human nature, which Rousseau thought to be good, to become corrupted. These parts of the book would go on to inspire both the educational system of France during the revolution and the Montessori method. His simultaneously radical and reactionary ideas on women’s education would also earn tremendous attention.

It was a section on religion that would get the book banned, Rousseau exiled, and the bonfires lit, however. In this section, a catholic priest is depicted as suggesting that the real benefit of any religion is its ability to instill virtue in a person and that the particular religion it is doesn’t matter. This character also espoused unitarianism, rejected original sin, and thought little of revelation.

After reading the book, the French government issued a warrant for Rousseau’s arrest, causing him to flee to Switzerland. However, the Swiss had read the book too and told him he could not remain in Bern. After rejecting an offer to live with Voltaire, he fled to Môtiers, which was governed by Prussia at the time. This arrangement only lasted two years, however, as local priests decided he was the Anti-Christ and drove him from town.

He continued to move frequently for the next few years. His reputation later improved, and he ultimately moved back to France, though his experiences instilled paranoia in him that never entirely went away.

Karl Marx

Admit it; this one doesn’t surprise you.

Marx is well known as the father of modern communism and one of the few modern philosophers who can be said to have created an entire philosophy, Marxism, largely by himself.

After the closure of his radical newspaper by Prussian authorities in 1843, Marx moved to Paris to continue writing. It was there that he met several people who would be significant partners and rivals in his life, including Fredrick Engels and Mikhail Bakunin. It was at this time that the philosophy that we now call “Marxism” began to take shape. In 1845, at the request of the Prussian government, the French closed down his paper there and threw him out of the country. Marx moved to Brussels. He also lost his Prussian citizenship at this time and would be stateless for the rest of his life.

After promising the Belgian government he wouldn’t write on contemporary politics, he returned to more abstract philosophy while also keeping contacts with radical organizations. It was here that he wrote The Communist Manifesto in 1848. Later that year, as riots and revolutions spread across Europe, the Belgian government accused Marx of being part of a plot to launch a revolution in Belgium. The evidence for either side of the argument is thin, but he was arrested nonetheless. He subsequently fled to newly Republican France after getting out of jail.

After a brief stay in France, he returned to Cologne, where he continued to agitate for a full communist uprising in the aftermath of the German Revolution. This failed to materialize, and Marx was again thrown out of his homeland.

He returned to Paris, but they didn’t want him either. He moved to London, where he would remain for the remainder of his life.

Hannah Arendt

A German-American philosopher who wrote on the banality of evil and the methods of totalitarian regimes, Arendt is one of the greatest political philosophers of the 20th century.

Born into a Jewish family in Germany, Arendt came of age just before the rise of Nazism. A bold writer, she wrote numerous essays attacking the Nazi party both before and after they came to power. She associated with many leading Zionists and used her access to state resources to study anti-Semitism in hopes of an announcement to the world on how bad things were in Germany.

She was turned in by a librarian for “anti-state” propaganda. Arendt and her mother were both arrested by the Gestapo and held for several days. As their journals were in code, the police were unable to determine precisely what they had written, and they were released to await trial.

They fled immediately. Crossing a mountainous path by night from Saxony to Bohemia, they worked their way to France. Hannah lost her citizenship and made due as she could in Paris. Just before the German Invasion of France in 1940, she was arrested by the French as an “enemy alien” and detained. After the fall of France, she and her family again fled the Nazis, this time to America, by way of Portugal.

It is little wonder that her greatest works focus on totalitarianism. In her masterpiece, The Origins of Totalitarianism, she devotes a lengthy chapter to the issue of human rights and refugees undoubtedly inspired, at least in part, by her time as one.