Few of us desire true equality. It’s time to own up to it

- Democratic values, especially equality before the law and equality of opportunity, are complex and often contradictory.

- Many pleasures of modern life are intertwined with the suffering of others, casting into doubt the morality of our daily choices.

- Authenticity and understanding demand facing the uncomfortable truths about the state of our society.

“Please God, make me good, but not just yet.”

The plea by Augustine of Hippo — later, St. Augustine — was probably an ironic quip; translational accuracy has his seeking to be made chaste and celibate. His words come to mind when I hear declarations of allegiance to democratic values of justice, liberty, and equality of opportunity. Whether the plea be to God or gods — to Humanity, the State, or Law — “not just yet,” as we shall see, applies to those allegiances; to think otherwise is a self-deception. We should own up.

The “not just yet” is sometimes a “not at all.” It is not at all possible to become celibate after years of marriage; and it is not at all possible to secure some of the values just mentioned. That is not because the securing would be “too late,” as it is in the case of celibacy, but because it is nonsense to think we have any clear idea of what constitutes those values in application.

I tiptoe, gradually approaching that nonsense and more.

(In)equality before the law

Democratic values are praised by “the great and the good,” by political, corporate, and religious leaders, by citizens and humble thinkers. (I include myself qua the humble.) They appear in constitutions, amendments, and declarations: witness those of the U.S. and United Nations. One example is “All are equal before the law.” It is false.

Equality before the law would require equality of representation, but certain defendants engage lawyers with expensive and erudite silver tongues whereas others, impoverished, defend themselves with stumbling incoherence. Equality before the law is also undermined by whims, prejudices, and legal interpretations, differing from judge to judge, jury to jury. It loses further credibility once we remember that many people lack resources to gain access to the law.

The above defects relate to how things are. Maybe genuine equality before the law could in principle be instituted, with everyone having equal access and equally good representation, judges, and juries. Were that possible, beneficiaries of current inequalities, whatever their lip-service to equality, would, I am sure, urge “not just yet.”

Access is important for other democratic values. Consider the right to vote. Exercising that right is easy for many but for others, burdensome — for those overwhelmed or juggling poorly paid jobs, large families, ill health, and voter registration requirements. Related deceits are the claims of “free and fair elections,” “the people” having spoken, and senators insisting they had been elected to do this or that. On what bases could such claims be properly justified?

The Land of Justice

Tiptoeing further into unclarity, consider the much-loved mantra of promoting “equality of opportunity.” I present the Land of Justice.

The Land was once akin to the U.S. and Great Britain with extremes of poverty and wealth. Children from deprived homes effectively lacked opportunities available to the well-to-do. To correct for that, the Land enabled all children to receive appropriate attention to their diverse needs, such as education, housing, and healthcare. No longer were the wealthy to secure competitive advantage for their offspring via additional tuition, serene study spaces, and cultural exchanges. Discrepancies, of course, remained in home life, so, with Plato in mind, the Land developed community upbringing, ensuring fair conditions for all.

Now, those who wave the flag of equal opportunities would not, I am sure, want equality of opportunity to go so far. The Land, though, dissatisfied with the focus solely on nurturing and environmental impingings, went further. Eyes could not be closed to nature’s unfairness in the distribution of talents.

Some children were naturally mathematically inclined, others not; some naturally driven, others easy-going. The mantra “all fetuses are equal” led to genetic manipulations of embryos such that children developed into adults with the same high level and spread of abilities, motivations, and desires to satisfy society’s needs. That uniformity was necessary, otherwise unfairness in opportunities would have arisen: some could have been lucky, wanting and being allocated flute playing, whereas others unlucky, ending up as sewage workers. (I pass over the Land’s handling of sexual inequalities whereby currently, for example, male average longevity is lower than that of females.)

No longer are job interviews required; lotteries determine who does what with suitable rotations between jobs. No one suffers unfairly. They recognize that they are equally talented, doing what they want. None expects to be paid more than others; none disparages the work of others.

The Land of Justice has expelled much sheer luck — good and bad — that currently exists through nature and nurture, violating fairness. True, some good fortunes and misfortunes remain — lightning strikes one, not another — and while chess games usually end in draws, distractions sometimes affect only one player, leading to exciting non-draws.

With the Land’s “equality” application so comprehensive, the individuality of individuals, the foothold, is largely lost. Providing equal opportunities requires differences in people and treatments, but also differences to remain. Which differences to erase, which to endorse? Those are grey areas. We should own up: The best we do is muddle through. Muddle also arises when I ask what sort of person I could have been — while maintaining the foothold of remaining “me.”

The Land of Justice has cast asunder values conflicting with fairness — values grounded in attachments to my loves, friends, family. Ethnicity, pronoun preferences, and linguistic infelicities ought typically to be irrelevant when the law assesses a case; matters are otherwise when romance is in the air. The Land’s justice offends a basic feature of human life, highlighted in Friedrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil:

“Isn’t living assessing, preferring, being unfair, being limited, wanting to be different?”

The answer is “yes,” but only so far. We should take ownership of bafflement in determining “how far” as also when values of autonomy, liberty, and authenticity are in play.

We are surrounded by a cacophony of opinions, discussions, and advertisements. The observations here may be benignly thought-provoking in contrast to shrieking newspaper headlines, but what constitutes readers’ resultant “authentic” beliefs and desires? Corporate promotions, teasing us into unhealthy foods, drinks, and gambling ways, are often welcomed — part of a “free society” in which people (with money) are at liberty to buy as they choose — yet governmental urgings for healthier living are condemned as the “nanny state” undermining free choice.

Joy entails suffering

Allow me to widen the need to “own up.” Here is Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra:

“Have you ever said Yes to a single joy? O my friends, then you said Yes too to all woe. All things are entangled, ensnared, enamored.”

Much of what we enjoy is delivered courtesy of considerable suffering: children in the Congo scraping cobalt for lithium-ion batteries; seamstresses in squalid sweatshops producing fashionable clothing; animals caged in awful conditions. That goes on right now. We try to forget. For some, the focus is past injustices; hence, I add: It is all very well to pull down statues and rename buildings, showing outrage at earlier racisms, horrors, and slavery, but far more owning-up is needed. Today’s outraged cannot escape the benefits of infrastructures, institutions, and wealth derived from man’s past inhumanity. Protestors march on highways of exploitation.

How are we to live with ourselves, redeem ourselves, entangled as we are in the world’s history? Nietzsche wrote of the greatest burden, the “eternal recurrence,” of our lives being repeated eternally as they are, no déjà vu even. That repetition is a nonsense — any repeat “exactly the same” collapses into the original — but curiously the idea may highlight a question: How well disposed can we be to our lives, affirming them unconditionally, despite the surrounding horrors?

Simone de Beauvoir, in conversation with Simone Weil, emphasized the quest for meaning in one’s existence. Weil responded, “It’s easy to see that you’ve never gone hungry.” That should bring us up sharp. Philosophical reflection can distance us from feeling the plight of others.

Muddling through

I risk owning up to a deeper muddle.

If we accept current understanding of our biology, then every thought, every reading of words — every smile, vibration of vocal cords, or keyboard tappings by way of response — all result from neurological changes, whimsical-like electrical impulses and chemical signals. Have we any idea how those neurological events give rise to thoughts that express sense (when they do) and not just sense but also (one hopes) sometimes truth? That baffling reflection itself is open to the same challenge — as is this expression of it.

I can offer again only that we muddle through. We should do our best, despite not knowing what in the end constitutes the best. At the very least, we should embrace humility — and own up. Karl Marx wrote:

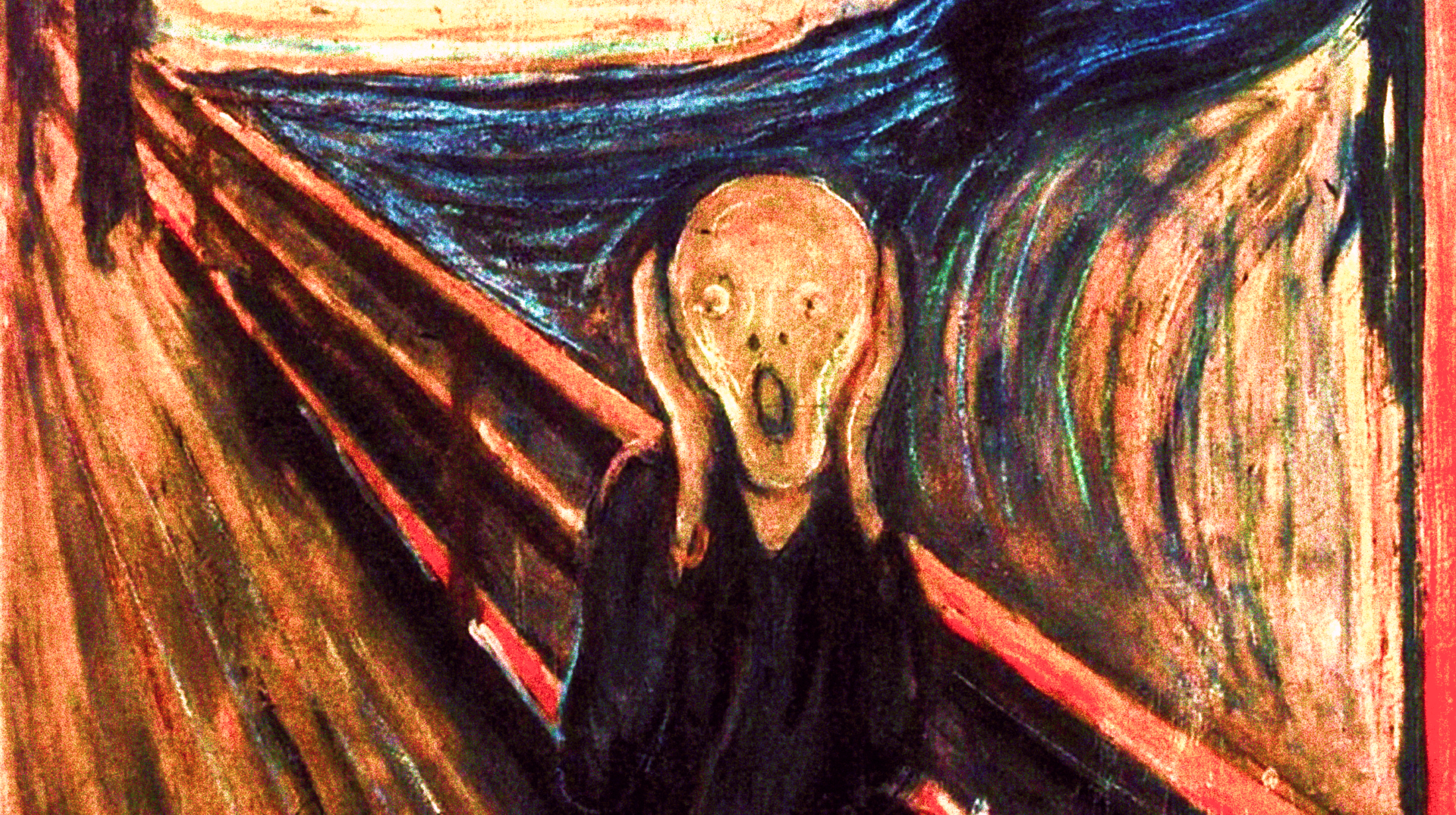

“Perseus wore a magic cap that the monsters he hunted down might not see him. We draw the magic cap down over eyes and ears as a make-believe that there are no monsters.”

Whether it be metaphysics or morality, the political or social, we should certainly remove the cap and confront the monstrous bafflements outlined above. Whether nonsense or not, whether our beliefs, values, and actions are determined by biology or not, as dinner approaches, we still have to choose — the red dress or blue? — and act as if we are making free choices.

And, as darkness descends and our lives meet with reflection, is it not also an act, a pretense, a deception, if we view them with satisfaction, happiness even, despite knowing of our inescapable entanglements in the horrors of the world, past, present and, no doubt, future? Can we ever be well disposed, truly so, to the world and how we live? Ought we not to own up and answer that question with a despairing “no”? Or…

Do we now pull down the cap all the more firmly, persuading ourselves that the monsters outlined in the thoughts above are all make-believe — and no “owning up” is required?

Peter Cave is a popular philosophy writer and speaker. His new book, How to Think Like a Philosopher: Scholars, Dreamers and Sages Who Can Teach Us How to Live, is now available from Bloomsbury.