System 1 vs. System 2 thinking: Why it isn’t strategic to always be rational

- It is true that the unique human ability to reason is what allows for science, technology, and advanced problem-solving.

- But there are limitations to reason. Highly deliberative people tend to be less empathetic, are often perceived as less trustworthy and authentic, and can undermine their own influence.

- Ultimately, the supposed battle between head and heart is overblown. Instead, we require a synthesis of both to make good decisions and live happy lives.

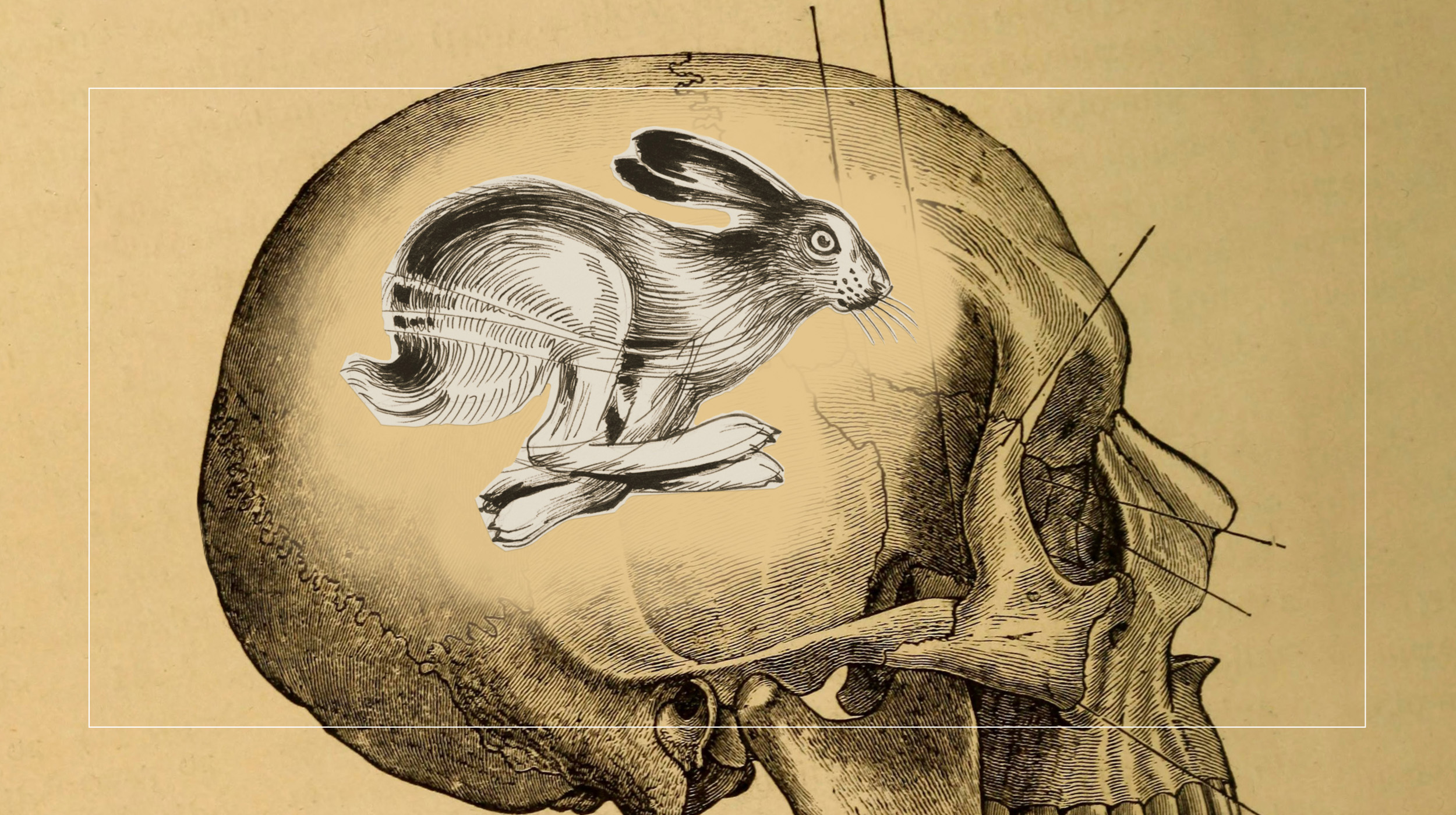

Daniel Kahneman’s bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow brought decades of research in judgment and decision-making to the popular consciousness. The key insight from Kahneman’s book is that people have, in essence, two minds: one that allows for rapid intuitive responses and one that allows for slower and more reflective deliberation. Furthermore, it is broadly thought that these two ways of thinking, often referred to as “System 1” and “System 2,” are entrenched in conflict, with our emotional intuitions often winning over our cold, calculating deliberations.

Indeed, the uniquely human ability to reason has seemingly had a tough go, recently. Misinformation is spreading on social media, political polarization is rising, science is being ignored. The much lauded ability for humans to stop and reflect does not seem to be winning in the battle against the very human tendency to rely on our gut feelings and intuitions.

Fortunately, human intuitions are often amazing things. We can immediately recognize the face of someone whom we have not seen in years. Chess grandmasters can intuitively identify thousands of unique potential configurations of chess pieces simply by looking at the board.

It’s not head vs. heart

It’s time to reframe the classic battle between our heads and our hearts, between our reason and our intuition. These faculties aren’t in a fight for your mind; rather, they are simply for different things. They facilitate different types of human success. “Reason” is often viewed as an unambiguous positive, but the reality is not so straightforward.

Consider the following problem, adapted from the (now classic) Cognitive Reflection Test:

A bat and a ball cost $110 in total. The bat costs $100 more than the ball. What does the ball cost?

Did you say $10? Most do, as this is the response that pops into our minds intuitively.

But the correct answer is $5. (If the ball costs $10, then the bat would need to cost $110, since it is $100 more than the ball. In total, that is $120.)

What this problem illustrates is the strength of our ability to reason (and the potential pitfalls of our intuition). To get the answer correct when first encountering this problem, one generally has to spend some time and effort thinking about it. Intuition isn’t good enough.

And, indeed, research has shown that people who do better on tests like this — that is, people who are more prone to engage in analytic or deliberative reasoning processes — differ in meaningful ways from people who tend to rely more on their intuitions. For example, people who are more deliberative are less likely to hold religious beliefs and are more likely to identify as atheists. They are also better able to distinguish between “fake news” and real news and are less prone to seeing profundity in pseudo-profound bullshit, to holding beliefs that are counter to the scientific consensus on several issues, to believing falsehoods about COVID, and to believing false conspiracies.

Of course, being a more deliberative thinker is associated with better academic performance, financial literacy, higher income, better job performance, and (more generally) better basic decision-making skills. It often pays to deliberate.

The downside of deliberation

This, however, is not the whole picture. People who are more analytic are also less empathetic. Reason may help you win a debate, but empathy is more useful for mending fences and maintaining relationships. Indeed, holding religious beliefs is associated with greater happiness and stronger moral concern. People who are more analytic are also less romantic and, in some contexts, may be more argumentative.

Deliberation may also influence how people look at you. Individuals who are more calculating in how they cooperate are seen as less trustworthy. Furthermore, spending too much time deliberating could be seen as a sign of low confidence or low capacity, which may undermine influence. Choices under deliberation are also seen as less authentic. These intuitions about deliberation aren’t completely unfounded because deliberation facilitates strategic thinking, which can make people less cooperative and less charitable in some contexts.

Our intuitions are also important for creativity. Although deliberation does facilitate some forms of creativity, continued deliberation can undermine important “Aha!” moments (relative to using unconscious incubation).

Deliberation can also hurt performance when doing highly trained tasks, for example, when making decisions in expert contexts. One would not want a firefighter who runs into a burning building to second-guess themselves. They are good at their job precisely because they have trained their intuitions to be smart. Deliberation also can lead to overthinking, which can hurt the reliability of eyewitness testimony and can inhibit statistical learning (that is, our ability to implicitly pick up on regularities in our everyday lives). While spending more time thinking can increase confidence, that may not always be justified.

The limits of reason

What this illustrates is that there is a general misunderstanding of what our ability to reason actually does or what it is for.

Reason allows us to gain a more accurate understanding of the world, and it can facilitate goal pursuit. That is very important. It helps us make better decisions in some contexts. It also allows us to develop new technologies and solve significant puzzles in our lives. But, at the same time, reason is not necessarily the path to happiness. There is value in our intuitions and gut feelings. They represent an important aspect of what it means to be human and should not be ignored.

The take-away is that we should be more mindful of what we expect from our own cognition. The question is not whether we should trust our reason or our intuition; rather, we can find agreement between what our heart wants and what our reason says.

Galileo once noted that “where the senses fail us, reason must step in,” a conclusion very much consistent with that of Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. Galileo and Kahneman are correct, of course, but this is not the whole picture. Perhaps we should add, “Where reason fails us, our intuitions must step in.” And this happens more than we might think.