4 practical life lessons from Taoism

- Taoism is an ancient Chinese philosophy and religion founded by the legendary sage Lao Tzu.

- While the philosophy can be paradoxical and abstract, it also has many practical life lessons to offer.

- Such lessons include engaging meaningfully with the world and learning the path toward “effortless action.”

Taoism (also written Daoism) is a religion, philosophy, and set of practices that arose in ancient China. Established by the semi-legendary Lao Tzu, and the slightly better accounted for Zhuangzi, its various forms can lay claim to millions of followers around the world.

Yet, many aspects of Taoism remain poorly understood. While most philosophies can become watered down as they are popularly dispersed, Taoism gets the worst of it. This ancient school of thought is often reduced to little more than “go with the flow, bro.” It can even be treated as so abstract that there’s nothing practical to be gleaned from it. Here, we’ll go over four life lessons from Taoism that you can use every day.

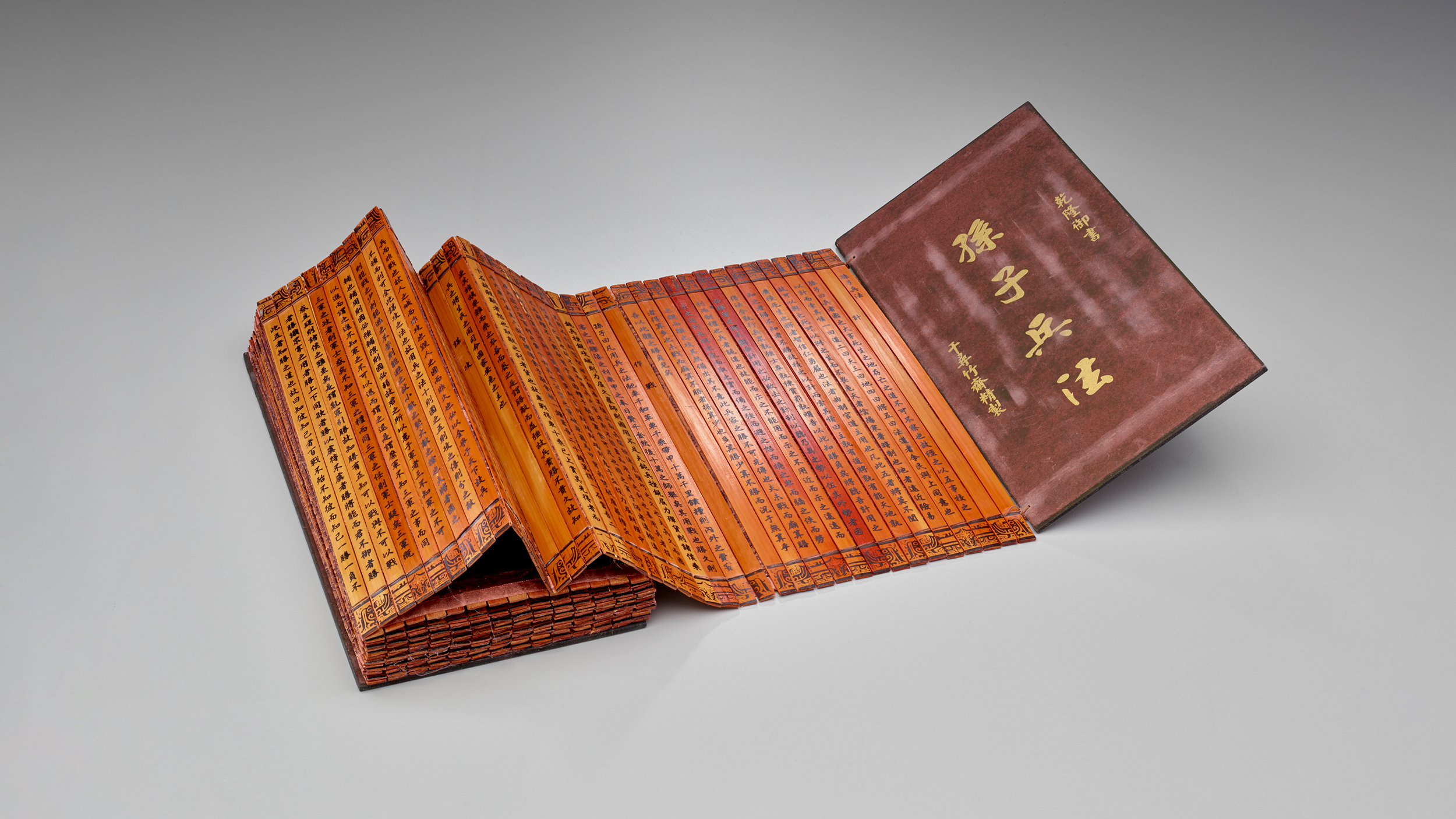

Before we begin, a word of warning about, well, words. As a philosophy, Taoism is extremely skeptical of language. The first line in the Tao Te Ching is “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao. / The name that can be named is not the eternal name.” As such, anything written here will be a little bit wrong because it is written. (Sorry about that.)

The Way is right in front of you

As mentioned, philosophical Taoism can seem terribly abstract. The Tao Te Ching contains paradoxical and seemingly contradictory lines that can baffle even careful readers. It is easy to suppose that this is a philosophy for hermits living on mountains or, at the very least, those who can afford long sabbaticals from society.

Not so. Understanding how the world works is a key part of Taoism, and that requires engaging with it. Large parts of the Tao Te Ching are specifically concerned with how to govern societies in accordance with the Tao — something that is difficult to do if you’ve abandoned civilization.

The Tao, in its purest form, is the unifying, all-pervasive essence of reality. Situations evolve following the Tao. The more you understand it, the more you can understand the cause-and-effect relationships that connect everything, as well as how your actions factor in.

Even if you aren’t the ruler of an ancient Chinese state, there is still practical advice to be had here. For instance, suppose you’re going into an important meeting. How you interact with others will have major effects on whether it is successful. If you go in and express anger, frustration, and rage, you’re probably going to wreck the meeting. On the other hand, if you take the Taoist view that flexibility is strength and act justly, mildly, and compassionately, you create the atmosphere necessary to facilitate more favorable outcomes.

While it would seem like you didn’t do as much in the second story, your understanding of the connections between actions, people, and effects allowed you to act with the Tao, which is to the benefit of everyone.

Be spontaneous

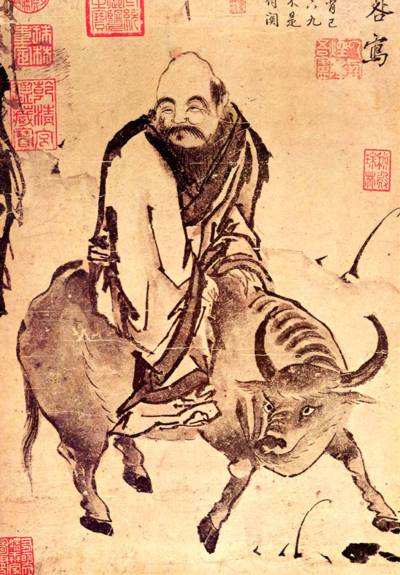

Zhuangzi, the second most important thinker in Taoism after Lao Tzu, explains that the path to “spontaneity” is to be found in rigorous practice and study.

Consider, Zhuangzi asks, the allegory of the butcher. The butcher has been working in his trade for decades and can now cut meat perfectly without thinking about it. In fact, he handles the meat with such skill that he has not had to sharpen his knife for years. How did he reach this level? Simple, he spent decades honing his craft.

For Zhuangzi, “spontaneous” does not mean “random.” It instead refers to how the butcher has come to understand his craft so well that he instinctively grasps what must be done. He can act without conscious effort and still finds himself following the Tao.

This ability is not limited to sages or professionals. Most people are familiar with the sensation of not having to think about what they are doing as they practice their hobbies, play sports, or drive along a familiar road. Zhuangzi points to this as a source of joy and a way of enjoying even the most mundane parts of life.

See simplicity in the complicated.

Lao Tzu

Achieve greatness in small things.

Take a broad perspective

Many philosophies encourage people to see beyond themselves. Taoism agrees but adds that the human perspective is fairly limited. After all, if the Tao is everything, why would the human perspective have a monopoly on truth?

Zhuangzi explains this again through allegory. Many of his stories take the point-of-views of animals and use the same language used to tell stories about humans. In his famous butterfly dream, the Chinese philosopher dreams he is a butterfly without any awareness that he is human. He flutters about from flower to flower until he awakens and realizes he is in reality a man who dreamed himself to be a butterfly. The tale is meant to explore the subjectivity and elusiveness of reality.

While other stories are more obviously metaphorical, the choice of using animal protagonists is deliberate. Zhuangzi is making the important point that breaking out of your limited perspective can provide new insights and a better understanding of the world around you.

This idea can be viewed in contrast to Confucian beliefs, which firmly place humans in the center of the material world. This strikes Taoist thinkers as misguided. Instead, Taoist thought provides a way to understand your place in a larger whole that goes far beyond human society.

Practice wu-wei (by not practicing it)

Wu-wei roughly means “inaction” or “effortless action.” It is one of the better-known aspects of Taoism, but not always the best understood.

The idea, according to philosopher Edward Slingerland, is to “try not to try.” It is being able to intuitively know what to do in a situation and to do it without spending cognitive energy (much like Zhuangzi’s butcher). In many ways, it can be thought of as a flow state for things we don’t often associate with flow states.

But it also goes beyond that. A person acting with wu-wei would be acting in harmony with the Tao. Action that seems “natural” but that goes against the cycles of the universe would not count.

There are several proposals on how to do this. The earliest Taoists suggested dropping out and returning to a simple life. The philosopher Mencius hybridized Confucian ideas with Taoist ones and argued that wu-wei existed but needed a little encouragement.

So don’t worry if you have to try at these lessons before they become more effortless. It’s not easy.