More than half of us are prone to “remembering” false memories

Do you remember where you were on 9/11? While most Americans immediately explain the details of the moment they found out about the attack on the World Trade Center, 40 percent of them are wrong.

Mere days after the attack, over 2,000 Americans were questioned about their experiences. Researchers followed up a year later, three years later, and a decade later. Nearly half of respondents reminisced inaccurately.

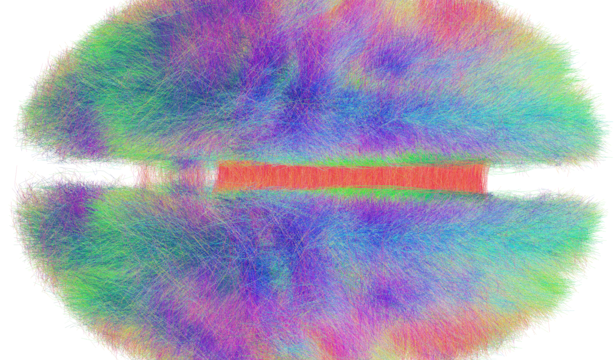

Humans have terrible memories. Part of the reason is the way we remember. When an event happens we file it via our brain’s weigh station, the hippocampus. When we recall the event it returns piecemeal, influenced by everything that’s occurred since. The more we retell a story the stronger the recall—and the more likely it will be revised.

“Memory is a poet,” Marie Howe once remarked, “not an historian.”

Like all verse, we can wax poetic over golden ages or reconstruct nightmares. Memory informs our identity. How we move forward in life depends on how we remember our past. Not only do we poorly reconstruct our experiences, we’re also susceptible to false memories. Tell yourself a lie often and it becomes truth.

A recent study published in Memory confirms this. A team of researchers from three separate countries assessed over 400 memory-report transcripts to better understand the mechanisms behind false beliefs. Pulled from eight different reports with no clear set of shared criteria, the researchers settled on seven concepts they felt adequate for describing the characteristics of autobiographical memories. This study reveals startling evidence regarding just how gullible humans are.

Take subjects implanted with false memories. Participants that reject the supposed event outright are unlikely to develop one. Yet others are more suggestible. If there is even an iota of doubt (or belief) regarding the imagined event, a process of questioning the possibility begins. A narrative arc is constructed. Eventually the event is taken as historical fact even though invented.

We think in narrative; we construct our lives as stories. Events barely noticed become foundational creation myths down the road. Worse, false events influence and shape the future.

Like Pizzagate.

One of the more disturbing drivers and consequences of the recent election is the proliferation of fake news, such as the absurd notion of a reported pedophilia dungeon turning into real gunfire at a D.C. pizza shop. Fake news is nothing new, though part of what makes it so difficult to discern involves agreeing as to what it is.

Satire? Propaganda? Advertising ploy? A little bit of all, depending on who’s writing it and the willingness of the believer. Gullibility is a neurological quirk: we’re more likely to believe what we are predisposed to, regardless of evidence against it.

Enter vaccines. To better understand the anti-vaccination movement, a research team based at Dartmouth mailed four separate types of pro-vaccination literature to nearly 2,000 parents. One stated there has been no scientific evidence relating vaccines to autism; another highlighted the dangers of the diseases vaccines prevent; the third featured photos of children suffering from said diseases; the final was a story about an infant who almost died from measles.

The team spent three years only to discover it didn’t matter which leaflet each parent received. Those predisposed to believing vaccines are evil did not change their mind. The neural connection, the memory they bought into—vaccines are bad—was so wired that no amount of contradictory evidence sufficed. Opposing literature sometimes fueled resistance in what is known as the backfire effect: you say do this, I do that instead.

How we’ve wired dictates what we believe, altering our memories to sync with the narrative inside of our heads. The researchers from Memory found that imagery and emotion are especially important markers for false memories. Returning to Pizzagate, there was a physical image—Comet Ping Pong Pizzeria—and an emotion to attach: namely, distrust and hatred of Hillary Clinton.

This leads to the second aspect of implanting false memories. Remember, only those at least somewhat willing to accept the possibility of the fake event will eventually formulate a false memory. The next cognitive leap occurs when they “remember” it. The imagination takes hold. Stories grow elaborate as the participant embellishes details that never occurred about an experience that never happened.

Researchers discovered that sprinkling in actual names and places makes the participant more susceptible. Doctored photographs are useful tools. Still, imagination reigns supreme. When false imagery was present the false memory rate was 37.3 percent, compared to 19 percent when it was not.

That only gets the ball rolling. Once the memory is implanted recollection is no longer as important. As the authors state:

Belief in the occurrence of an event may be sufficient to influence behaviour, whether or not there is also an accompanying episodic recollection.

Of the over 400 reports studied, 30.4 percent of participants had false memories, while 53.3 percent accepted the fake event to some degree. When factoring in previously stated conditions—doctored photographs, idiosyncratic information, and imagination procedures—rates were even higher: 46.1 percent had a false memory; 69.7 percent displayed at least some acceptance. The researchers state:

One conclusion that can be made based on this study and on similar work is that it can be difficult to objectively determine when someone is recollecting the past, versus reporting other forms of knowledge or belief or describing mental representations that have originated in other sources of experience.

There is a lot of discussion about how to combat fake news and debate over how much influence invented stories have on our political and social landscapes. The ease of sharing news has merely exploited a longstanding neurological feature: memories are highly susceptible to alterations. As this electoral season has shown, those who understand how to manipulate facts are experiencing unprecedented power at the expense of our faulty memory machines. We might not remember, but they do.

—

Derek’s next book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health, will be published on 7/4/17 by Carrel/Skyhorse Publishing. He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.