The German election was boring, which is good news for Europe

- Germans do not like surprises, and the recent national election met expectations.

- Europe, and Chancellor Angela Merkel in particular, became famous for “muddling through” the continent’s multiple crises.

- While Germany’s political future is unknown, the nation will continue to dominate Europe.

As goes Germany, so goes Europe. Now, at the end of the Angela Merkel era, that statement is as true as ever. The German election sent voters to the polls to elect a new chancellor after 16 years. The whole continent watched, and it cared — something that is rarely the case for other European nations.

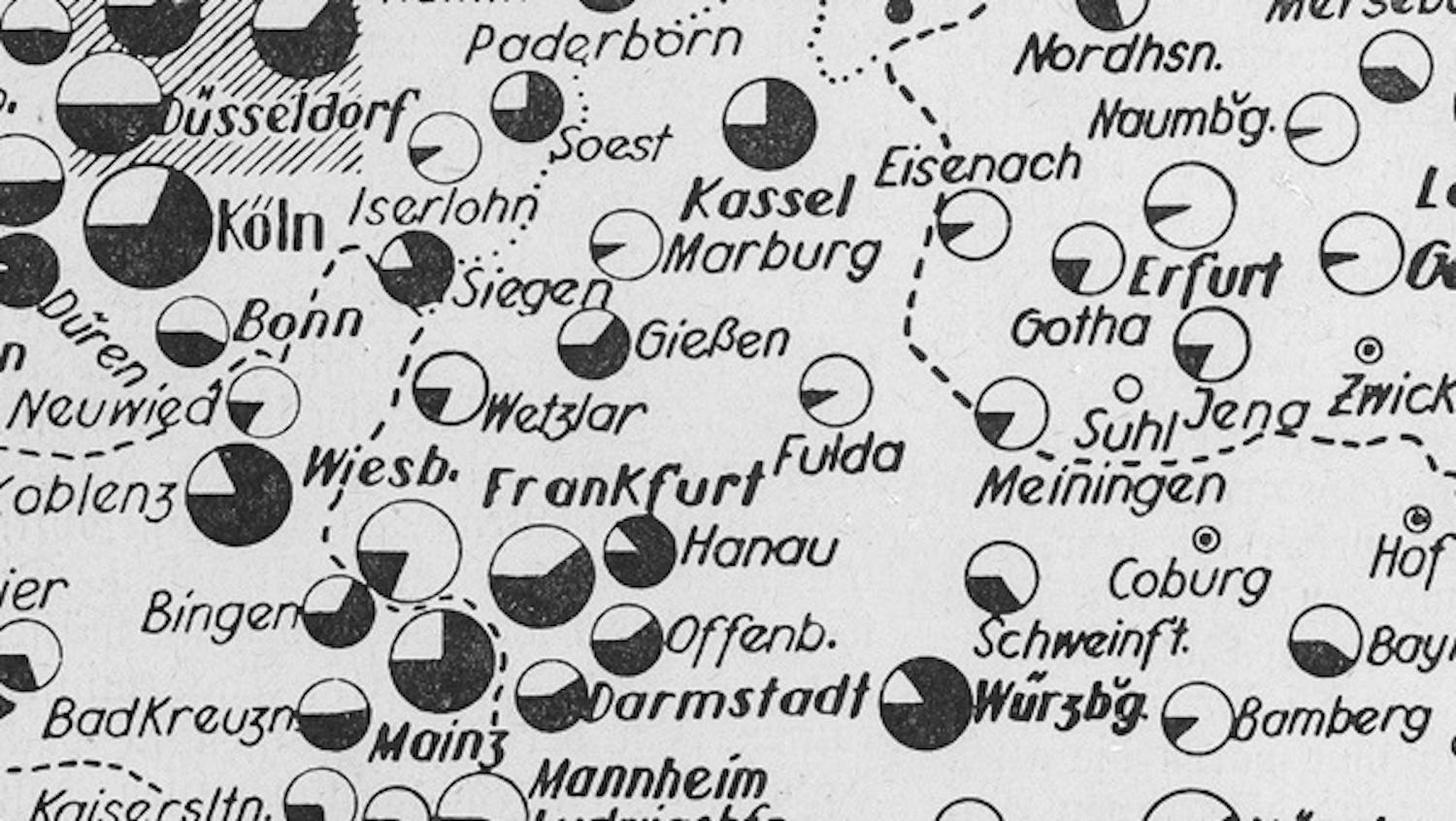

The results were mixed, and no party got anywhere close to an outright majority. The center-left SPD barely edged out Merkel’s center-right CDU, and Germany is now in for a (perhaps lengthy) period of coalition-building. Based on the vote’s results, the country likely will see a coalition that pairs one of the two historically dominant parties — the CDU or, far likelier, the SPD — at the helm of a grouping that probably will include the ascendant Greens and the classically liberal FDP.

Other variations are possible but would be a surprise, and a major hallmark of the Merkel era is a palpable German distaste for surprises. Thus, even though an agreement will be tough to reach between the two potential junior coalition partners, there is little reason to speculate otherwise at this point.

German election yields stability with a dash of uncertainty

Still, some of the reactions from observers outside of Germany show the regard with which German power is held in Europe broadly. Scanning the broadsheets in Italy, for example, readers might find this election characterized as a “double revolution,” referring to the revival of the moribund SPD alongside the fall of the post-Merkel CDU. More dramatically, there is talk of the “end of the first republic,” one founded and operated upon the surety of the two dominant centrist parties, which are now reduced to splitting about half of the votes between them.

A sense of trepidation is felt for EU institutions, where the short-term fear is that delays in forming a new German administration will lead to delays in important negotiations on matters such as Europe’s outdated Stability Pact (an agreement on fiscal rules) or cooperation on European defense.

Greater nervousness is reserved for the bigger question: Is Germany entering an era of more political fragmentation? (As Hans Kundnani points out, the likely three-party coalition would be the first of its kind in Germany since 1957.) And if that is indeed the case, how could it impact Berlin’s leadership at the EU level?

Muddling through to success

Geopolitics teaches us that individual leaders make much less of a difference than is supposed because they are greatly limited by the constraints that they face. Even so, a leader like Angela Merkel succeeds best when she becomes the expression of her people’s will, and in Germany’s case, that will remains in position to guide Europe to a large extent, for better or for worse.

Merkel succeeded, whether or not one likes her policies, because she understood this. As George Friedman points out, she was there as the idea of the EU took full effect, and she was there for the string of crises that threatened to break it apart immediately. She understood how crucial the Union is for the survival of her own country’s export-dominated economy. She rarely needed to say that out loud, instead being malleable enough to give ground on the international stage when necessary — but always in the German interest. She also understood the importance for the whole continent of maintaining at least some form of unity and the reliance of that unity on some basic level of standard-keeping. So, her administration was rigid enough and even ruthless with countries like Greece and Italy when it was possible and the situation called for it.

The EU lost Britain in the process. But in the run of history, that is not much of a surprise. Amid the many following tremors of Grexits, Frexits, Nexits, and Italexits, Europe, for a time, stood firm. “Muddling through” became the definitive description of the age and Merkel its icon, and while it was never a complimentary quip, it described a real achievement. (Just look at the sociopolitical chaos that has unfurled in so many parts of the globe over the same period.)

For those of us watching German politics from the outside, we will wonder what comes next, even if, as Kundnani emphasizes, the September vote was not a change election. Only Germany will carry German-sized sway on the European stage at any time in the foreseeable future. Only Germany is capable of producing leaders that can offer singular guidance outside of their own borders and serve as lightning rods to absorb criticism and protect the European house. Talented leaders can emerge elsewhere, of course, but they face too many constraints to be a true substitute.

Many questions for post-Merkel Germany

While this may have not been a change election, it nevertheless marked the end of the Merkel era. As such, what becomes interesting isn’t this German election but the next. Will German leadership maintain the qualities that allow it to avoid fragmentation? Looking at the likeliest coalition, with the SPD as the major party, we have seen elsewhere in Europe that center-left governments with a classically and economically liberal component tend to alienate their voters. Can this coalition avoid that?

For the ascendant Greens, will their rise to power be the source of their own downfall in the next election if compromising with the FDP means that they cannot deliver on their new supporters’ expectations? With Merkel gone, will the incoming leaders be talented enough to manage the continuing political divide between East and West Germany? Will her successors manage the country’s growing emphasis on addressing climate change and housing issues, without alienating average citizens? In sum, will German voters continue to value a strong center in their national politics, or will they peel off more and more to the benefit of future fringe parties?

These are questions of domestic interest looking forward, but they interest Europe as well. And the very last thing Europe wants is an interesting election in Germany.