Ask Ethan: Will dark energy cause the Big Bang to disappear?

- Dark energy is causing the universe’s expansion to accelerate, driving galaxies and light farther away from us.

- In the far future, no signals beyond our Local Group will remain visible, eliminating the evidence we used to discover the Big Bang.

- But a series of very clever measurements, if we’re savvy enough to make them, could still reveal our cosmic history to us.

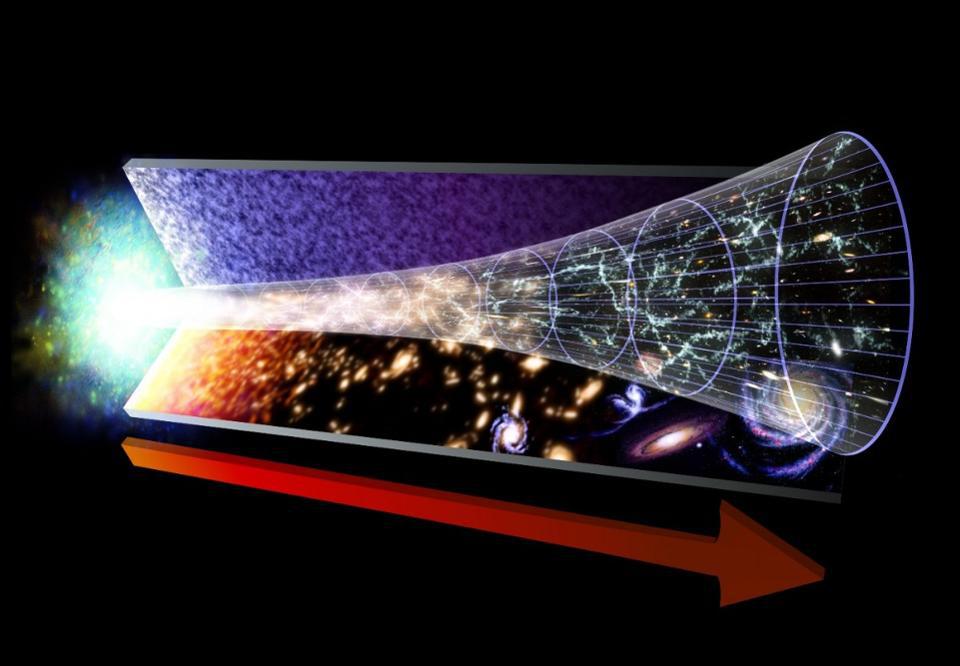

13.8 billion years ago, the universe as we know it — full of matter and radiation, expanding and cooling and gravitating — came into existence with the onset of the hot Big Bang. Today, we can see and measure the signals that travel to us from enormous cosmic distances, enabling us to successfully reconstruct the universe’s history and how we came to be. But as time passes, a novel form of energy in our universe — dark energy — increasingly dominates the expansion of space. As dark energy takes over, it accelerates the universe’s expansion, which gradually removes the key information needed to draw the conclusions we’ve reached today.

It’s enough to make one wonder: If we were born in the far future instead of today, would we be able to learn about the Big Bang at all? That’s what Patreon supporter Aaron Weiss wanted to know, asking:

“[A]t some point in the future, all objects not gravitationally bound to us will recede away. [T]he only points of light in the night sky will be objects in our Local Group. At that point in time, will there be any evidence of the universe’s expansion that might suggest to future astronomers that there are/were stars and galaxies beyond what would be visible to them? Would they have lines-of-site that lead to nothing but the CMB?”

Does our ability to answer fundamental questions about the universe hinge upon when and where we happen to exist in cosmic history? Let’s look to the far future to find out.

Today, there are four major pieces of evidence that we typically consider as the cornerstones of the hot Big Bang. The whole reason we consider the Big Bang as the unchallenged scientific consensus is because it’s the only framework, consistent with the laws of physics (like Einstein’s General Relativity), that explains the following four observations:

- the expanding universe, discovered through the redshift-distance relation for galaxies

- the abundance of the light elements, as measured through various gas clouds, nebulae, and stellar populations across the universe

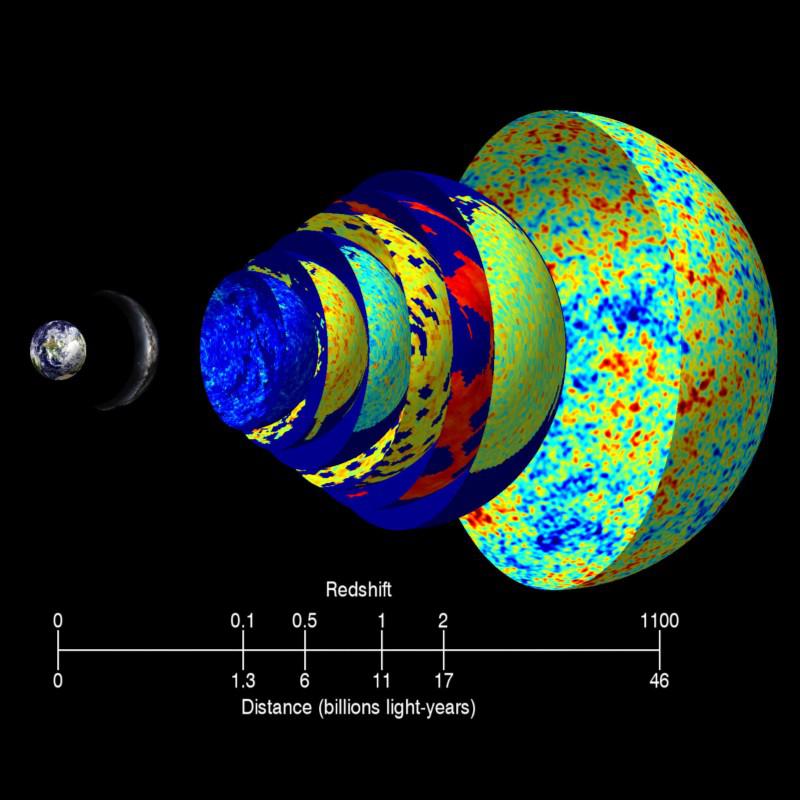

- the leftover glow from the Big Bang, which is today’s cosmic microwave background, as directly detected via microwave and radio observatories

- the growth of large-scale structure in the universe, as revealed by galaxy evolution and their clumping and clustering patterns seen across cosmic time

It’s important to remember that cosmology, like all branches of the astronomical sciences, is fundamentally driven by observations. Whatever our theories predict, we can only compare them to observations in the universe. The way we discovered each of these phenomena in our universe has its own remarkable story, but it’s a story that won’t be around permanently for us to always observe.

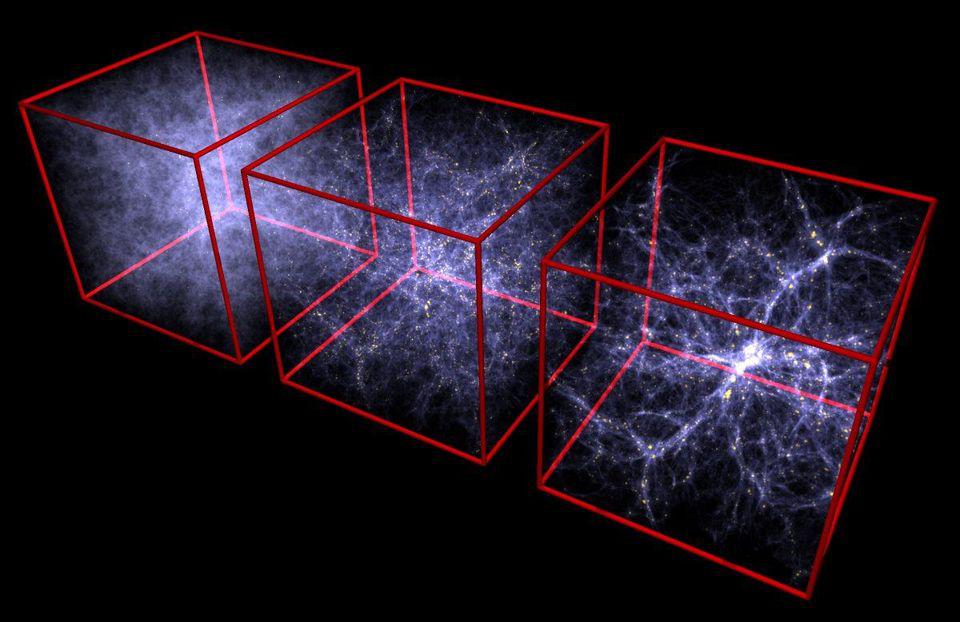

Credit: Volker Springel/MPE

The reason is straightforward: the conclusions that we draw are informed by the light that we can observe. When we look out at the universe with our best modern tools, we see lots of objects within our own galaxy — the Milky Way — as well as many objects whose light originates from far beyond our own cosmic backyard. Although this is something we take for granted, perhaps we shouldn’t. After all, the conditions in our universe today won’t be the same as those in the distant future.

Our home galaxy currently extends a little over 100,000 light-years in diameter, and it contains roughly ~400 billion stars, as well as copious amounts of gas, dust, and dark matter, with a wide variety of stellar populations: old and young, red and blue, low-mass and high-mass, and containing both small and large fractions of heavy elements. Beyond that, we have perhaps 60 other galaxies within the Local Group (within about ~3 million light-years), and somewhere around 2 trillion galaxies littered throughout the visible universe. By looking at objects farther away in space, we’re actually measuring them over cosmic time, which enables us to reconstruct the history of the universe.

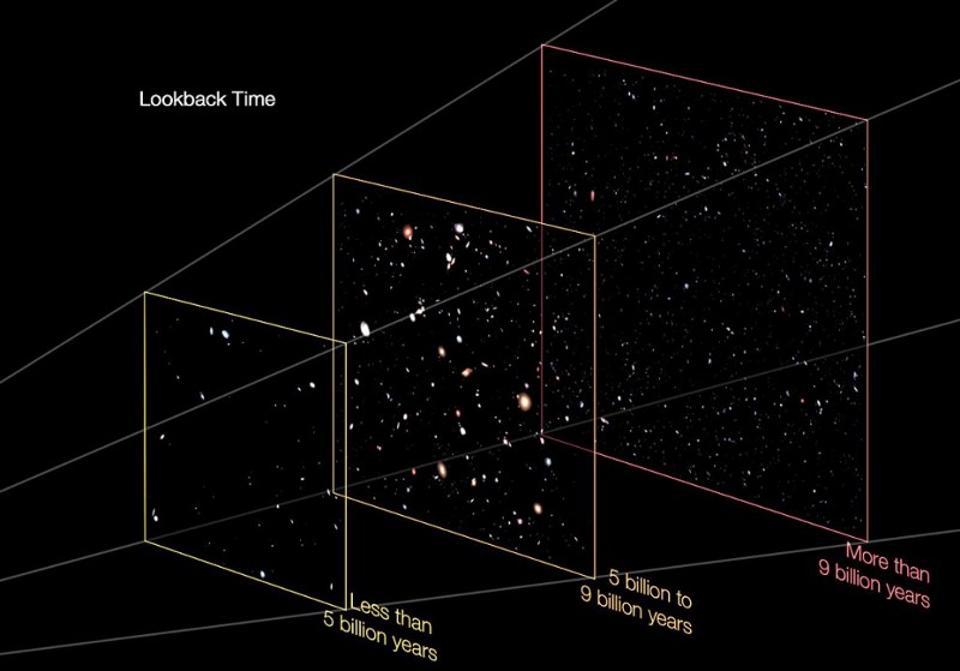

Credit: NASA, ESA and Z. Levay, F. Summers (STScI)

The problem, however, is that the universe isn’t merely expanding, but that the expansion is accelerating due to the existence and properties of dark energy. We understand that the universe is a struggle — a race, of sorts — between two main players:

- the initial expansion rate that the universe was “born” with at the onset of the hot Big Bang

- the sum total of all the various forms of matter and energy within the universe

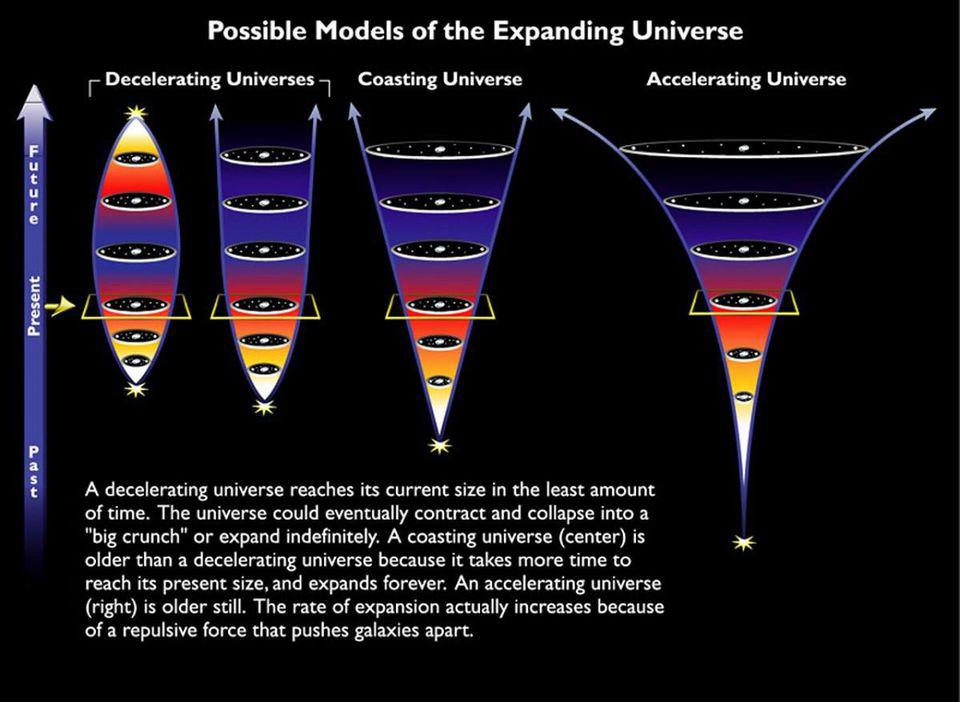

The initial expansion compels the fabric of space to expand, stretching all unbound objects farther and farther away from one another. Based on the total energy density of the universe, gravitation works to counteract that expansion. As a result, you can imagine three possible fates for the universe:

- expansion wins, and there isn’t enough gravitation in all the existing “stuff” to counteract the initial large expansion, and everything expands forever

- gravitation wins, and the universe expands to a maximum size and then recollapses

- a situation between the two, where the expansion rate asymptotes to zero, but never reverses itself

That was what we expected. But it turns out that the universe is doing a fourth, and rather unexpected, thing.

Credit: NASA & ESA

For the first few billion years of our cosmic history, it appeared as though we were right on the border between eternal expansion and an eventual recontraction. If you were to observe distant galaxies over time, each would have continued to recede from us. However, their inferred recession speed — as determined from their measured redshifts — appeared to slow down over time. That’s just what you’d expect for a matter-rich universe that was expanding.

But about six billion years ago, those same galaxies suddenly started to recede from us more quickly. In fact, the inferred recession speed of every object that isn’t already gravitationally bound to us — i.e., that’s outside of our Local Group — has been increasing over time, a finding that’s been confirmed by a wide suite of independent observations.

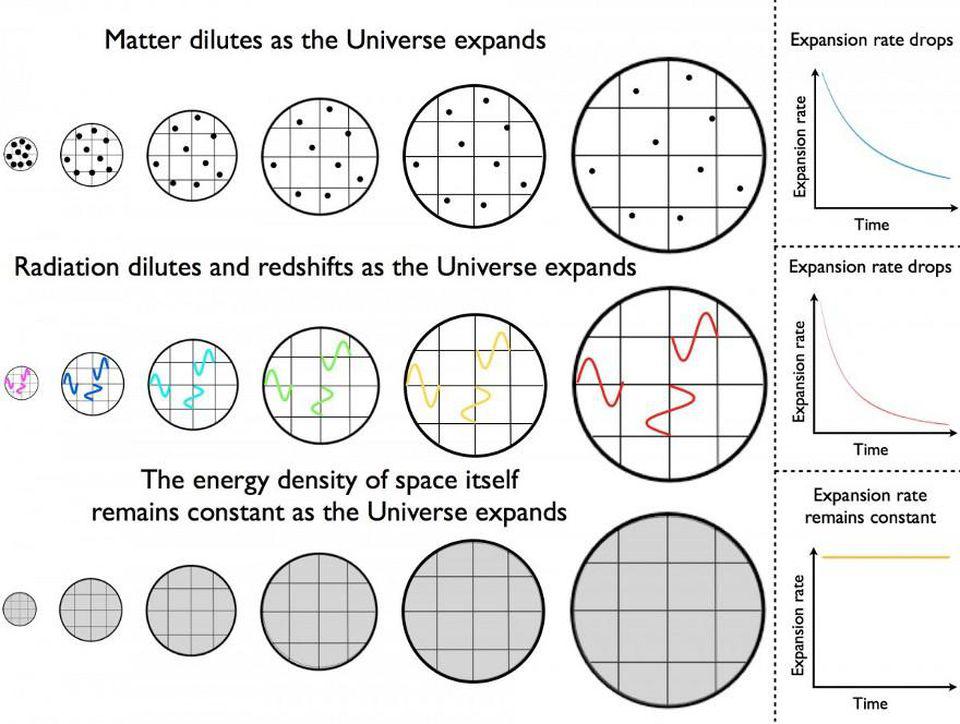

The culprit? There must be a new form of energy permeating the universe that’s inherent to the fabric of space, which doesn’t dilute but rather maintains a constant energy density as time goes on. This dark energy has come to dominate the energy budget of the universe, and will take over entirely in the far future. As the universe continues to expand, matter and radiation get less dense, but dark energy’s density remains constant.

This will have many effects, but one of the more fascinating things that will occur is that our Local Group will remain gravitationally bound together. Meanwhile, all of the other galaxies, galaxy groups, galaxy clusters, and any larger structures will all accelerate away from us. If we had come into existence at a later date after the Big Bang — 100 billion or even a few trillion years after the Big Bang, as opposed to 13.8 billion years — most of the evidence we presently use to infer the Big Bang would, by then, be completely removed from our view of the universe.

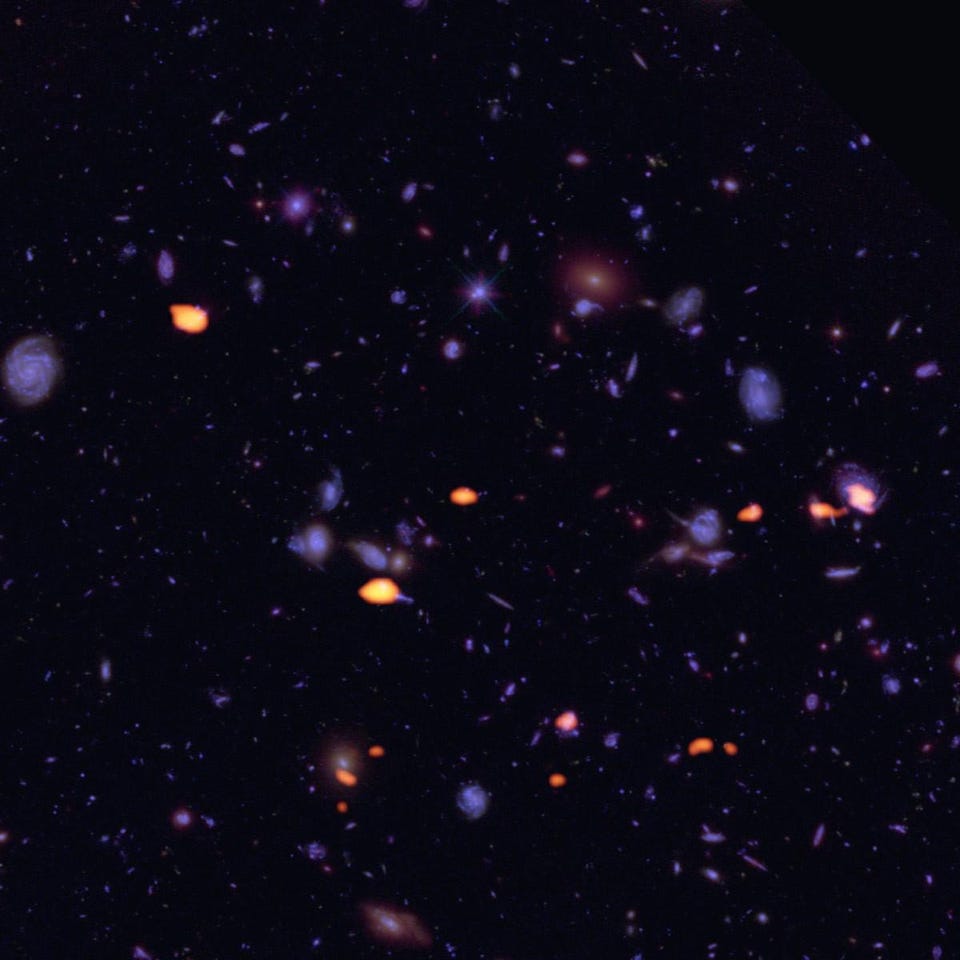

Our first hint of the expanding universe came from measuring the distance to, and the redshifts of, the nearest galaxies beyond our own. Today, those galaxies are only a few million, to a few tens of millions, light-years away from us. They’re bright and luminous, easily revealed with the smallest telescopes or even a pair of binoculars. But in the far future, the galaxies of the Local Group will all merge together, and even the closest galaxies beyond our Local Group will have receded away to tremendously large distances and incredible faintnesses. Once enough time passes, even today’s most powerful telescopes, would reveal not a single galaxy beyond our own, even if they were to observe the abyss of empty space for weeks on end.

This accelerated expansion, brought on by the dominance of dark energy, would also steal from us critical information about the other cornerstones of the Big Bang.

- Without any other galaxies or clusters/groups of galaxies to observe beyond our own, there’s no way to measure the large-scale structure of the universe, and infer how matter clumped, clustered, and evolved throughout it.

- Without populations of gas and dust outside of our own galaxy, particularly with different abundances of heavy elements, there’s no way to reconstruct the early, initial abundance of the lightest elements before the formation of stars.

- After a tremendous amount of time, there will be no cosmic microwave background anymore, as that leftover radiation from the Big Bang will become so sparse and low-energy, stretched and rarified by the expansion of the universe, that it will no longer be detectable.

On the surface, it appears that with all four of today’s cornerstones gone, we’d be completely unable to learn about our true cosmic history and the early, hot, dense stage that gave rise to the universe as we know it. Instead, we’d see that whatever our Local Group becomes — likely an evolved, gas-free, and potentially elliptical galaxy — it would appear that we were all alone in an otherwise empty universe.

(Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA and N. Gorin (STScI); Acknowledgment: Judy Schmidt)

But that doesn’t mean we’ll have no signals at all that could lead us to conclusions concerning our cosmic origins. Many clues would still remain, both theoretically and observationally. With a clever enough species investigating them, they might be able to draw correct inferences about the hot Big Bang, which could then be borne out through the process of scientific investigation.

Here’s how a species from the far future could figure it all out.

Theoretically, once we discovered the present law of gravity — Einstein’s general relativity — we could apply it to the entire universe, arriving at the same early solutions that we discovered here on Earth during the 1910s and the 1920s, including the solution for an isotropic and homogeneous universe. We would discover that a static universe that was filled with “stuff” was unstable, and therefore must be expanding or contracting. Mathematically, we would work out the consequences of an expanding universe as a toy model. But on the surface, the universe would appear to be exhibiting a steady-state solution. However, observational clues would still exist.

(Credit: NASA/ESA/Hubble/F. Ferraro)

First off, stellar populations within our own galaxy would still come in tremendous varieties. The longest-lived stars in the universe can persist for many trillions of years. New episodes of star formation, although they’d become somewhat rare, should still occur, as long as our Local Group’s gas doesn’t become totally depleted. Through the science of stellar astronomy, this means we’d still be able to determine not only the age of various stars, but their metallicities: the abundances of the heavy elements with which they were born. Just as we do today, we’d be able to extrapolate back to “before the first stars formed, how abundant were the various elements,” and we would find the same abundances of helium-3, helium-4, and deuterium that the science of Big Bang nucleosynthesis yields today.

We could then look for three specific signals:

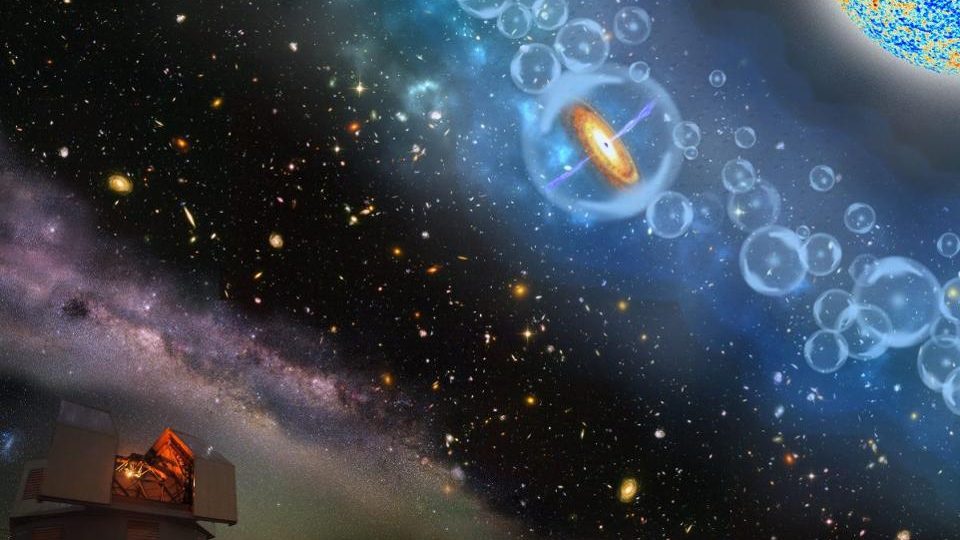

- The severely redshifted leftover glow from the Big Bang, with just a few extremely long-wavelength radio-frequency photons arriving from all over the sky. A large, ultra-cool radio observatory in space could find it, but we’d have to know how to build it.

- An even more severe and obscure signal would arise from very early times: the 21-cm spin-flip transition of hydrogen. When you form a hydrogen atom from protons and electrons, 50% of the atoms have aligned spins and 50% have anti-aligned spins. Over timescales of around ~10 million years, the aligned atoms will “flip” their spins, emitting radiation of a very specific wavelength that gets redshifted. If we knew the wavelength and sensitivity ranges in which we needed to look, we could detect this background.

- The ultra-distant, ultra-faint galaxies that lie at the edge of the universe but never fully disappear from our view. This would require building a telescope large enough and in the proper wavelength band. We’d just have to know enough to justify building something so resource-intensive to look to such great distances, despite not having any direct evidence of such objects nearby.

Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

It’s an incredibly tall order to imagine the universe as it will be in the far future, when all of the evidence that led us to our present conclusions is no longer accessible to us. Instead, we have to think about what will be present and observable — both obviously and only if you figure out how to search for it — and then imagine a path towards discovery. Even though the task will be more difficult hundreds of billions, or even trillions, of years from now, a civilization smart and savvy enough would be able to create their own “four cornerstones” of cosmology that led them to the Big Bang.

The strongest clues would come from the same theoretical considerations we applied back in the early days of Einstein’s general relativity and the observational science of stellar astronomy, in particular an extrapolation to the primordial abundances of the light elements. From those pieces of evidence, we could figure out how to predict the existence and properties of the leftover glow from the Big Bang, the spin-flip transition of neutral hydrogen, and eventually the ultra-distant, ultra-faint galaxies that can still be observed. It won’t be an easy task. But if uncovering the nature of reality is at all important to a far-future civilization, it can be done. Whether they succeed, however, is entirely up to how much they’re willing to invest.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!