Ask Ethan: How Can You Be So Sure That COVID-19 Didn’t Happen From A Lab Leak?

The only doubts are completely unreasonable.

Where did the virus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, come from? Over the past few weeks, there’s been a tremendous push — largely among politicians but also among a small number of scientists — to bring an idea that’s largely been circulating among conspiracy theorists, the idea of a lab leak origin for the virus, into the mainstream. Numerous doctors, scientists, and intelligence officials have come forth, touting various reasons to believe that this virus, which has to date infected over 175 million people and killed nearly a confirmed 4 million worldwide, may not have originated in animals and spilled over, naturally, into the human population. Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of virologists in the world have derided every such scenario as implausible, leading to the “nightmare scenario” that scientists often face when it comes to contrarians: they’ve taken their case to the general public, who simply sees a two-sided issue where some scientists believe one thing and others believe the opposite. So what does the science actually say about this issue? That’s what Ahmed Hassan wants to know, asking:

“how is it that this Coronavirus strain… just so happens to have developed and jumped from animal to human in the same district as China’s national virology lab? What are the chances?”

This is a question that lots of people have been asking, and while a number of strong assertions have been made, a lot of them completely ignore the science of modern virology. Here’s what is actually known.

It’s very hard to call the lab leak conspiracy an actual hypothesis, because there are so many versions of it floating around out there, rather than a conspiracy theory. For example:

- some assert that SARS-CoV-2 was created in a lab as part of a bioweapon program, and that China is covering it up,

- some assert that Dr. Fauci is directly involved, funding the program that funded the lab that created the virus,

- some assert that it was Dr. Zhengli Shi, the chief scientist for emerging disease at the Wuhan Institute of Virology and the world’s pre-eminent bat research, whose lab is responsible for the virus,

- some assert that it was a specific kind of banned and/or under-regulated research — gain-of-function research — that led to the laboratory modification of a pre-existing virus to bring about the origin of this disease,

- and others, still in support of the lab leak idea, claim that all of the above are conspiratorial nonsense, but that the virus — perhaps uncatalogued, unsequenced, or unreleased by researchers — was brought into the lab, infected one or more of the workers there, and then made it out into the general public.

Yet no matter which parts of this you do or do not subscribe to, it turns out that all of these components are extraordinarily unlikely when compared to what we call the “null hypothesis” of zoonotic spillover: that it naturally leapt from animals to humans.

I’ve already addressed many of the earlier objections here and here, but what about the gain-of-function option? How can we be certain that the virus wasn’t created in a lab? After all, we have genome editing tools, the CRISPR technique, and a recent piece in the Wall Street Journal — full of allegations that various aspects of this virus show that it was genetically engineered — laying out precisely how this could have happened.

Unfortunately for those of us who’d otherwise be curious about the idea of a lab leak, this story is full of holes, and cannot be how the virus was made. Here’s why.

All organisms have some sort of string of nucleic acids, like RNA or DNA, that encode their genome. An organism’s genome is sometimes referred to as its “genetic fingerprint,” where each unique species and each organism within the same species will have a genome that’s specific to that species and that organism. Despite the efficiency of tools that help organisms replicate, mutations still frequently occur, allowing subsequent generations to be different from the organism that originally replicated.

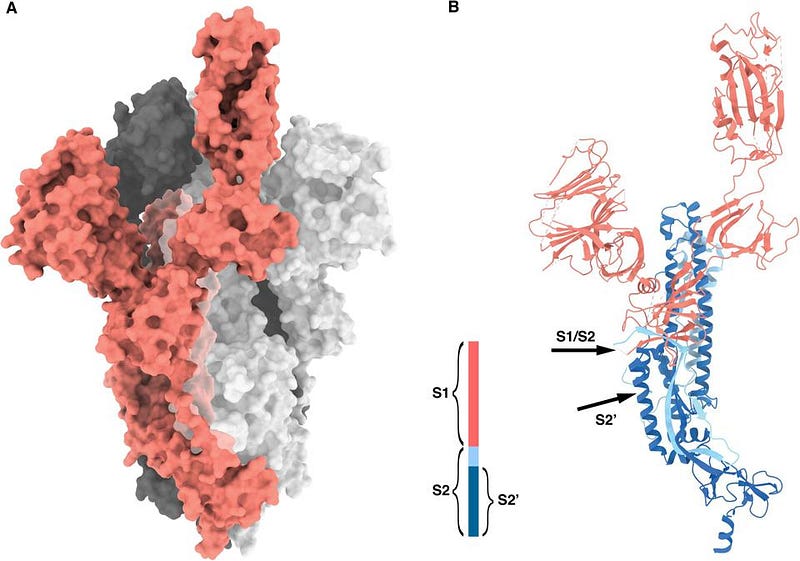

SARS-CoV-2, like all coronaviruses, is a virus with a crown-like shape to it, with various “spikes” on its surface. Those spikes are proteins, that the shape of those proteins enable the virus to bind to various cells. What’s being touted as a novel development is called the furin-cleavage site: the part of the spike protein that connects the bottom of the protein to the top of the protein, and controls how the tip of the spike can move around and bind to cells. The claims that have led some to believe it was manipulated by humans are:

- that furin-cleavage sites aren’t found in any other betacoronaviruses besides SARS-CoV-2,

- and that there are two arginine amino acids in that site, back-to-back, encoded with codons which are CGG-CGG.

Of the 64 possible combinations of codons in every three-nucleotide sequence, there are six possible codons that encode arginine. CGG is rarely found in coronaviruses, and back-to-back CGG-CGG codons have never been seen in other betacoronaviruses. The assertion is that the very existence of this furin-cleavage site is suggestive of a lab origin for the virus, and that the back-to-back CGG-CGG codons are the smoking gun.

Unfortunately, the only way one could reach this conclusion is if one deliberately, willfully misunderstand how viruses, evolution, and genetics all work. When you see a codon in a virus that differs from the more common codons, there are typically two things that could have occurred.

- You got a random mutation, and this mutation did not ruin the virus’s ability to replicate in the host creature that it was created in. This option is basically the same thing as finding a shiny pokémon in the wild: they’re rare, and they may even stand out as targets among their normal bretheren, but the mutation wasn’t disastrous to the virus’s survival capabilities.

- You got a mutation that made the virus more successful in, or more well-adapted to, the host creature.

That’s right: preferences for which codons encode an amino acid are a function not only of the pathogenic organism itself, but of the host organism that the pathogen is well-adapted to. You can, for example, go to this interactive tool that shows which codons are frequently used for encoding various amino acids in a variety of organisms, and you’ll find that each organism has its own unique set of codons that it prefers.

For a virus in an organism, therefore, you have to consider three things.

- How stable is this virus’s RNA? Anytime you alter a virus’s genetic sequence, because viruses are complex, highly evolved organism, there’s a good chance that the virus will no longer be able to replicate, to encode proteins, or to function the way an unaltered virus would; most changes you could make would make the virus less efficient at doing what it does than natural evolution did.

- How successful with this virus be in this particular host with this particular genetic sequence? If you were an E. Coli organism making a protein for use in a bacterium, for example, it would make no sense to choose CGG as a codon for arginine. That codon is disfavored by the host organism, and again introduces inefficiencies. CGG is just fine in human hosts, by the way; approximately 20% of our arginine codons are CGG.

- And finally, how well does the virus evade the host’s immune system? The most important function of the immune system is to recognize pathogens, and molecules known as pattern recognition receptors are how we do it. In particular, there’s a specific class of these known as TLRs (for Toll-like receptors), which function as pathogenic booby traps by looking for patterns that the host organism does not possess.

In other words, seeing CGG-CGG in your virus tells you almost nothing about the likelihood of the virus being engineered, but instead gives you information about the adaptations the virus has successfully made to a particular host or set of hosts.

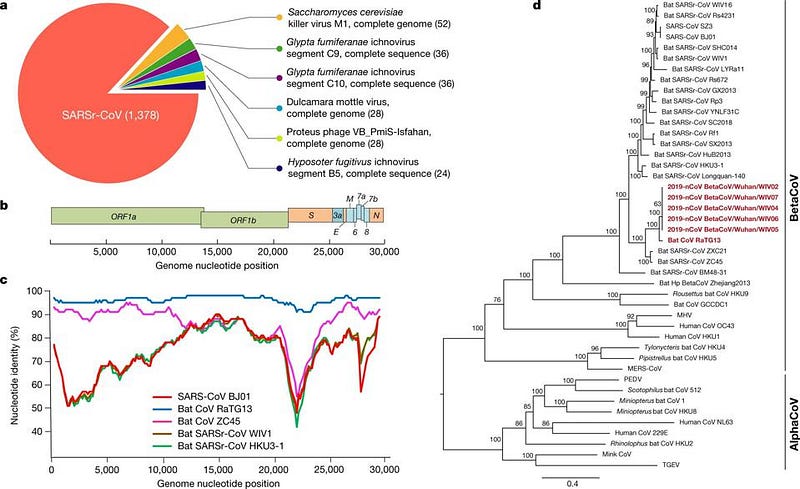

The assertion that furin-cleavage sites are rare in betacoronaviruses is patently untrue; in fact, a mapping of the genetic family tree of betacoronaviruses shows that they evolved multiple times, independently, in the evolution of the coronavirus family. Even more specifically, in detail, the genetic sequences at this site are completely consistent with natural evolution. Not only is there no smoking gun for genetic modification here, but these details, when you bother to learn them correctly, support the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 arose naturally.

So if it wasn’t created in a lab, does that mean the idea of a “lab leak origin” for this virus can be ruled out? Only one scenario remains: that the virus occurred naturally, was brought into the lab, and through a failure of containment through some sort of incredibly negligent procedure, one or more of the workers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology accidentally infected themselves, began infecting others in Wuhan, and then a superspreader event occurred at the infamous wet market, triggering the pandemic as we then became familiar with.

There is, of course, absolutely no evidence in support of this scenario. What’s often cited as circumstantial evidence for a lab leak is, in fact, not evidence at all. For example, many point to the fact that it’s been ~18 months, and no intermediary animal host for SARS-CoV-2 has been found. While it’s true that the intermediary for the original SARS was found after 4 months and the intermediary for MERS was found after 9, most intermediary hosts remain elusive for far longer. Ebola’s intermediary has remained elusive after 6 years; it took approximately 2 decades to find HIV’s intermediary. In fact, the exact origin of many viral diseases have never been determined. At the same time, we are certain there are viruses out there with the potential to leap from animals to humans that remain undiscovered in the wild.

Are we even looking in the right place? Wuhan is the largest city not only in its province, Hubei, but in all of central China. If we look at how pandemics have arisen in the past, and how they continue to arise today, it’s almost always due to contact between humans and animals. This can arise because of encroachment of humans onto wild animal populations, but it can also arise due to agricultural concerns, like farming and ranching.

You have to remember that the potential of a virus to jump to humans relies on chances: the more lottery tickets you buy, the greater the odds that you’ll eventually win. (Or, in the case of a “pandemic” lottery, for your species to lose.) For example, no one, in the history of HIV research, has ever become infected from an SIV (Simian immunodeficiency virus) in the lab. In the wild, SIVs are known to infect at least 45 different non-human primate species, and has jumped from animals to humans numerous times; that’s how we got HIV. In nature, chance events occur all the time.

But in the lab, it would take a catastrophic accident. While these do happen — someone shatters a test tube and cuts themselves with it, someone slips and accidentally stabs themselves with a syringe that contains a pathogen, etc. — they are incredibly rare. For this to have been a likely, reasonable source of the origin of SARS-CoV-2 in humans, there would have to be virtually no risk of zoonotic spillover from an animal population into humans. In a world where humans are:

- increasing their population,

- increasing the land areas that they occupy,

- taking away the natural wilderness habitats of wild animals,

- and engaging in large-scale animal farming and agriculture,

this simply isn’t true. A cursory look at previous pandemics shows how this plays out.

Pig farming is what has led and continues to lead to swine flus in humans.

Poultry farming is what has led and continues to lead to bird/avian flus in humans.

Civets, which were farmed in China and sold in animal markets, brought SARS-1 into humans (as the intermediary from bats).

Even though the closest naturally occurring virus to SARS-CoV-2 is a species of coronavirus found in horseshoe bats in a cave in Yunnan province — three provinces away from Hubei — bats probably aren’t the species we should be examining. Instead, as perhaps the top world expert on coronaviruses, Germany’s Christian Drosten, has stated, it’s incredibly plausible that carnivore breeding and the fur industry are responsible. In this (translated from German) interview, he explains why this is so probable:

“Viruses of the same species do the same things and often come from the same source. In Sars-1, this is scientifically documented, the transitional hosts were raccoon dogs and crawling cats. That’s assured. It is also certain that raccoon dogs are used extensively in the fur industry in China. If you buy a jacket with a fur collar anywhere, it is the Chinese raccoon dog, almost without exception. And now I can tell you that there are no studies in the scientific literature — none at all — that shed light on the question of whether raccoon dog breeding stocks or other carnivore breeding stocks, for example minks, carry this virus, Sars-2, in China.”

The fur industry itself is a $61 billion enterprise in China alone; perhaps the reason we haven’t found the intermediary host is because we’ve simply failed to look in the most likely place.

It is true that you cannot dismiss or rule out the possibility that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, originated in a lab and that’s how it came to humans. But the receptor binding domain, the furin cleavage site, and the specific genome of the virus support a natural, not a laboratory, origin. Based on the techniques claimed, it could not have been engineered in a lab.

The two possible origins, then, are from a naturally occurring virus that either arose from an extremely rare, and then covered-up, laboratory accident, or from animal agriculture, the latter of which has been responsible for the overwhelming majority of recent pandemics.

So feel free to ask yourself: what’s more likely? That an accidental event from a lab, where only a handful of workers have access to viruses that were collected from caves all around China, arose due to a rare and spectacular leak? Or that a prominent and popular industry, where workers are butchering animals that naturally eat bats day in and day out for decades, led a virus to jump from animals to humans?

The natural explanation isn’t just overwhelmingly likely in this instance, but is likely to be the cause of most, if not all, future pandemics. Baseless accusations are being levied here, similar to ones that have had catastrophic consequences in the past. Worst of all, these evidence-free allegations are intensifying bigotry and violence against Asian-Americans. In science, we are interested in what is true, not what makes us feel better about the world. Until and unless that evidence arises, the zoonotic hypothesis is the only one backed by a solid scientific foundation, while the lab leak idea remains firmly in the realm of conspiracy.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Starts With A Bang is written by Ethan Siegel, Ph.D., author of Beyond The Galaxy, and Treknology: The Science of Star Trek from Tricorders to Warp Drive.