What classic Russian literature can tell us about Putin’s war on Ukraine

- For centuries, Russian writers have struggled to define the country’s national identity.

- Some argued that Russia should Westernize; others believed Russia should form an anti-Western allegiance with other Slavic countries.

- One of the most influential supporters of Pan-Slavism was Fyodor Dostoevsky, who may have actually been rather sympathetic toward Putin’s cause.

In order to understand Russian history and culture, you must first understand Russian literature. Russia’s greatest novels — War and Peace, The Brothers Karamazov, and Fathers and Sons to name a few — were designed for purposes other than entertainment. They probe the human psyche and analyze socioeconomic issues to figure out how people are supposed to live their lives.

To say Russian literature had a profound effect on the structure of Russian society would be an understatement. Today, Russian school children are introduced to their country’s literary canon as early as the fifth grade, where texts are studied for their universal wisdom as well as their contributions to the current understanding of Russia’s national identity.

While Russia’s most influential writers have been dead for centuries, their contemporary readers do not treat them as relics of a bygone era. According to Nina Khrushcheva, granddaughter of communist leader Nikita Khrushchev and professor of international affairs at the New School in New York City, the Russian people are “used to living in fiction rather than reality.”

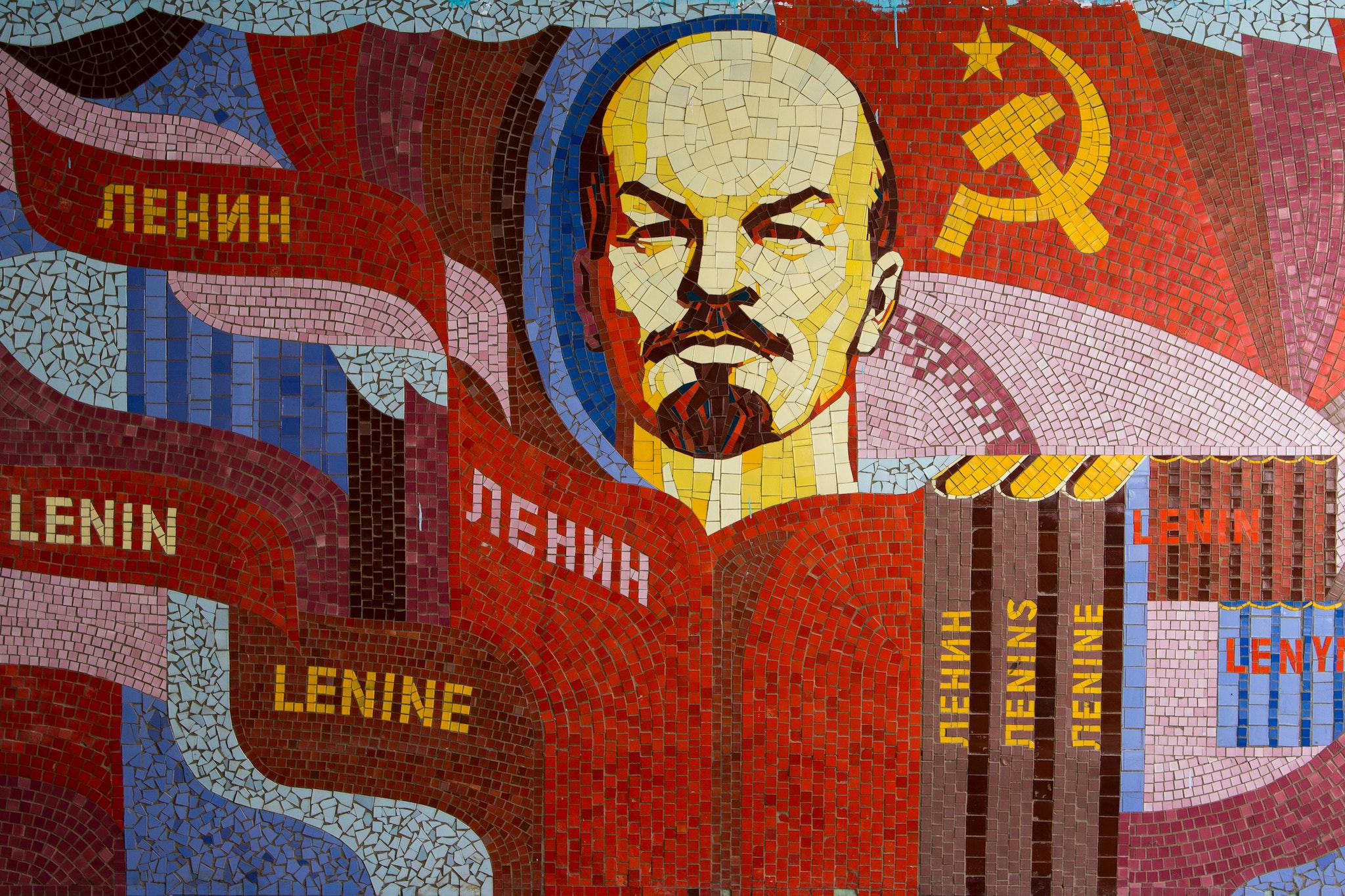

Just as Russian literature guides the daily lives of ordinary citizens, so too has it informed the worldview of Russian leaders. Vladimir Lenin, an avid reader who was well-versed in both Russian and Western literary history, once proclaimed that Tolstoy was “the mirror of the Russian Revolution,” arguing that his distaste of exploitation predicted and inspired Russia’s political transformations.

Putin also has professed an appreciation for Russian literature. In various interviews, he has listed Tolstoy and Dostoevsky as some of his favorite authors. To this list Putin would occasionally add: Ivan Turgenev, author of Fathers and Sons; Mikhail Lermontov, who also had a prolific career in the army; and Sergei Yesenin, an uncontroversial poet known for his idyllic verses about the countryside.

Suspicious of Putin’s cultural literacy, scholars have long noted the contradictions between the actions undertaken by his administration and the ideas presented in the books he claims to admire. This question has been around since Soviet times, but it acquired new significance following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last week.

Upon closer inspection, it seems that the relationship between Russia’s literature and its politics is not as simple as many had previously assumed. At its zenith, Russian literature was the literature of rebels and dissenters: well-intentioned intellectuals who condemned authoritarian regimes and envisioned societies that were founded on compassion rather than coercion.

Yet this describes only one aspect of Russian literature. Aside from capturing universal human experiences, Russian writers were also concerned with defining the overarching character of their country — a country scattered across both space and time — and its relationship to the Western world and its place in history. To those who are following the news right now, this should already sound familiar.

Tolstoy’s non-violent resistance to evil

It is important that we give credit where credit is due. Leo Tolstoy and Dostoevsky — Putin’s two favorite writers — each have created some of the most convincing arguments in favor of non-violent resistance to evil in the history of the human race. In a time when religious morality was decaying, these two revitalized faith in the goodness of God and, by extension, man.

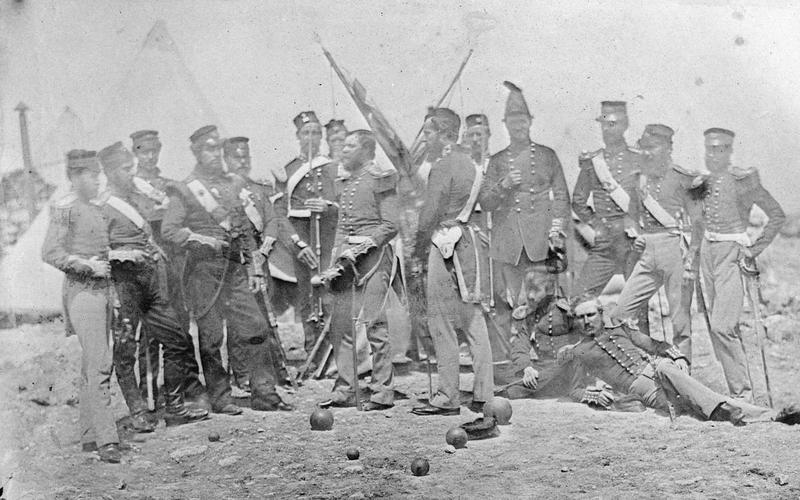

When Leo Tolstoy was 26 years old, he briefly fought in the Crimean War — a conflict which, much like today, Russia entered under the questionable premise that it was protecting Russian subjects residing in a neighboring state. The horrors of war deeply affected Tolstoy, leading him to adopt a pacifist attitude that he maintained for the rest of his life.

Like many of his fellow soldiers, Tolstoy arrived in the Crimean city of Sevastopol without fully understanding why he was there or what he was doing. Nor did he feel particularly compelled to find out, for the reality of war — carefully concealed from heroic myths and romanticized paintings — was so shocking, so inhumane, that any attempt at justifying it would turn out insufficient.

Tolstoy’s Sevastopol Sketches, a largely autobiographical recounting of the war, came out in 1855, and it is one of the first books to describe the devastating consequences of battle. Soldiers resemble skeletons with a “dull, corpse-like gaze.” Tolstoy even describes how the “sharp, curved knife” of a military doctor pierces the skin of wounded soldiers, causing them to regain consciousness.

“You behold the frightful, soul-stirring scenes,” Tolstoy wrote, setting the stage for a scene that he would return to many times over the course of his career. “You behold war, not from its conventional, beautiful, and brilliant side, with music and drum-beat, with fluttering flags and galloping generals, but you behold war in its real phase — in blood, in suffering, in death.”

In the trenches, Tolstoy came to the conclusion that our political justifications for war are mere propaganda stories, designed to raise the fighting spirits of foot soldiers. The hero of his writing, he declares, is neither the Ottoman nor the Russian Empire, but the truth — or the belief that, in war, everyone loses.

This belief was reinforced with each novel he wrote. Building on top of ideas that were introduced in War and Peace, Tolstoy’s novel Resurrection argues that people do not have the right to punish each other because the world is complex to the point that nobody is personally responsible and everybody ought to be held accountable for everybody.

Toward the end of his life, Tolstoy’s pacifism became inseparable from his religious convictions. Following his excommunication from the Orthodox Church, the author proclaimed unconditional love was the one and only rule that man should live by. This was the reason Lenin saw socialism reflected in Tolstoy, and the reason Tolstoy would protest Russia’s deadly invasion of Ukraine.

Russia’s national identity

In the early morning hours of February 24, 2022, Putin delivered a televised address in which he discussed the reasons for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The address, which sought to deny Ukraine’s independent statehood and highlight Russia’s historic struggle against Western powers, contained little to no hint of Tolstoy’s humanitarianism.

Putin did, however, echo another hallmark of classic Russian literature: the search for national identity. Critics have traced this search all the way back to Alexander Pushkin and Nikolay Karamazin, two of the literary canon’s founding fathers who, to quote one article, “strove to identify what it meant to be Russian, to belong in one way or another to the Russian imperial enterprise.”

Their striving was not unwarranted. Russia has always been a large, multicultural, multilingual, and multiethnic civilization, lacking a common history to unite its people. With one foot in Europe and another in Asia, Russians considered themselves to be neither fully European nor Asian, and constantly debated which direction the country should be facing.

Some were of the opinion that Russia should be Westernized: Peter the Great designed Saint Petersburg following a historic trip to Amsterdam, while writers incorporated Western art and ideas into their own work. Lenin, an internationalist, believed the October Revolution would ignite a global workers’ revolt that would conclude in industrialized Europe.

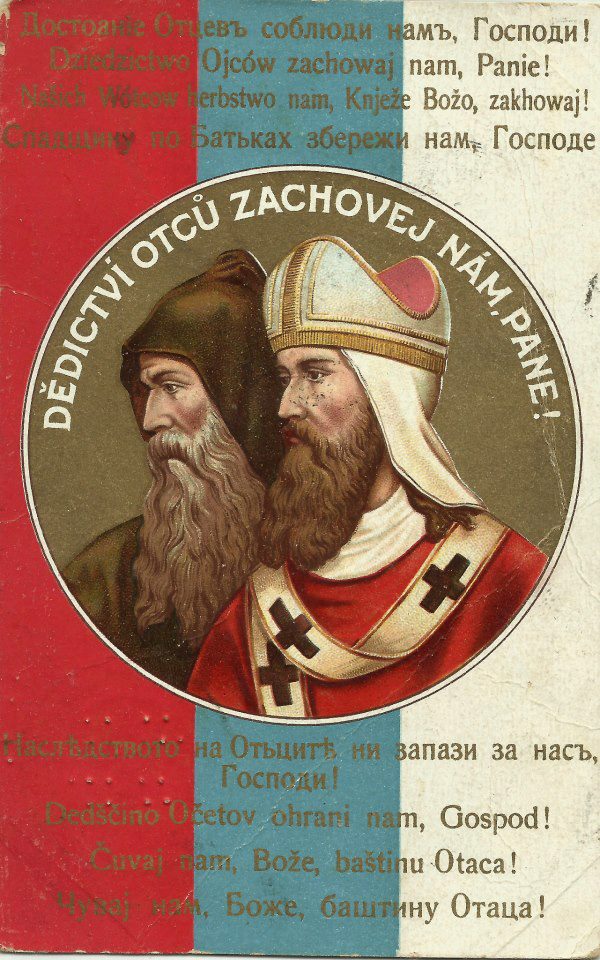

Attempts at Westernizing Russia sparked a countermovement calling for the country to distance itself from its neighbors. Followers of this movement believed that the Russian character, however elusive, was incompatible with Western values. Rather than joining Europe, they thought Russia should join forces with other Slavic countries to form a superpower capable of checking Western expansion.

This countermovement, also known as Pan-Slavism, is key to understanding Putin’s popularity in Russia, not to mention his attitude toward Ukraine. His speeches and essays reveal that Russia bases its claim to Ukraine not on the country’s former membership of the USSR but on its cultural heritage, which like Russia’s, can be traced back to the medieval Slavic federation of Kievan Rus’.

Pan-Slavism, which rose to prominence during the days of the Russian Empire, was staunchly suppressed by the Bolsheviks when they came to power in 1917. The idea that all the Slavic nations were connected across history contradicted Karl Marx, who emphatically stated that, eventually, the concept of states would wither away as the workers of the world united.

Although Pan-Slavism was briefly rejected, it was not forgotten. Like any ideology founded on chauvinism, it left a deep impact on the Russian people, who found in Putin someone that wanted them to express rather than repress their national pride. For better or worse, few people understood the source of this pride better than Russia’s premier psychologist: Dostoevsky.

Dostoevsky’s Pan-Slavism

Like Tolstoy, Dostoevsky believed in the inherent value of every human life. And, like Tolstoy, Dostoevsky had arrived at this conclusion via personal experience. In his youth, the author was arrested for discussing socialist literature and sentenced to die by firing squad. Fortunately, he was spared by a last minute pardon from the tsar himself.

The author’s brief encounter with death launched his religious reawakening, turning him from a pragmatist into a spiritualist. In his fiction, Dostoevsky would often recount the terror and despair he had felt while attending his own execution, and posited that the existential dread of this situation alone was more than enough to justify abolishing the death penalty.

As Dostoevsky’s faith in socialism dwindled, his devotion to Russia — its people, its culture, and its history — increased. After serving years of hard labor in Siberia, Dostoevsky returned to Saint Petersburg to found a literary journal with brother Mikhail. Its writers called themselves pochvenniki, men who advocated a common allegiance to and respect for Russia’s soil and natural resources.

Devotion to Russia was accompanied by antipathy, even hostility, toward European countries. Later in life, Dostoevsky traveled through Europe to seek treatment for his epilepsy and to escape creditors. In letters, he expressed a deeply rooted longing to return home while simultaneously reflecting on the many ways in which European people were spiritually inferior to Russians.

He daydreamed of a war between Europe and Russia and felt certain that Russia would win. The Russian spirit, Dostoevsky wrote in Dresden, will have “such sacredness that even we are impotent to fathom the whole depth of that force… nine-tenths of our strength consists just in the fact that foreigners do not understand and never will understand the depth and power of our unity.”

As Hans Kohn mentions in an article from 1945 titled “Dostoevsky’s Nationalism,” the author’s philosophy of humility and compassion is at odds with the enthusiasm he showed whenever the Russian Empire waged war to expand its territory. Dostoevsky waited for the moment when, in Kohn’s terms, “the Slav world under Russia’s leadership would fulfill its destiny.”

Dostoevsky used even stronger terms. “The present peace,” he wrote in his diary, “is always and everywhere much worse than war, so incomparably worse that it finally becomes outright immoral to maintain it… War develops in [man] for love of his fellow men and brings nations together by teaching them esteem for each other. War rejuvenates men.”

As early as 2018, Andrew Kaufman, a professor of Slavic languages at the University of Virginia, concluded that Putin had chosen Dostoevsky’s faith in Russian exceptionalism over Tolstoy’s belief in the universality of human experience. In light of the invasion of Ukraine and its perceived historical significance for Russians, one might argue Dostoevsky would have chosen Putin as well.