How to write like Edgar Allan Poe

- Gentle yet disturbing, “The Raven” is a classic example of how Edgar Allan Poe’s works touch us so deeply.

- Poe wrote about how he accomplishes this. In all great literature, there is an “under-current,” as if something is moving beneath the words.

- Poe is usually thought an early proponent of “aestheticism,” the belief that all art ought to be in the service of beauty.

“Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

’Tis some visitor,’ I muttered, ‘tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.’”

There are few lines in the history of poetry that are quite so evocative, quite so gently disturbing, as the opening to Edgar Allan Poe’s, “The Raven.” It has been dissected by generations of schoolkids and satirized by The Simpsons, and “The Raven” features regularly in people’s “top 10 favorite poems.” It’s no hard work to see why. The rhythm and meter of the lines are both pleasant to hear and fun to speak. But more even than this are the themes. Poe is seen as the leading light (or shuffling ghoul) of Gothic literature, and his macabre, sinister plots stay with you long after the final line.

Which, of course, is exactly what Poe wanted them to do. Poe’s work speaks to those parts of ourselves that don’t fit neatly into the world around us — the under-parts, perhaps. His writing presents terrifying ideas in gilded and pleasant prose. It’s horror with a delicious wrapping. And, like some cold poison creeping up our veins, there’s a frisson in its peril.

How, though, did Poe manage such a thing? Why do his name and his works stand out so proudly in the history of literature?

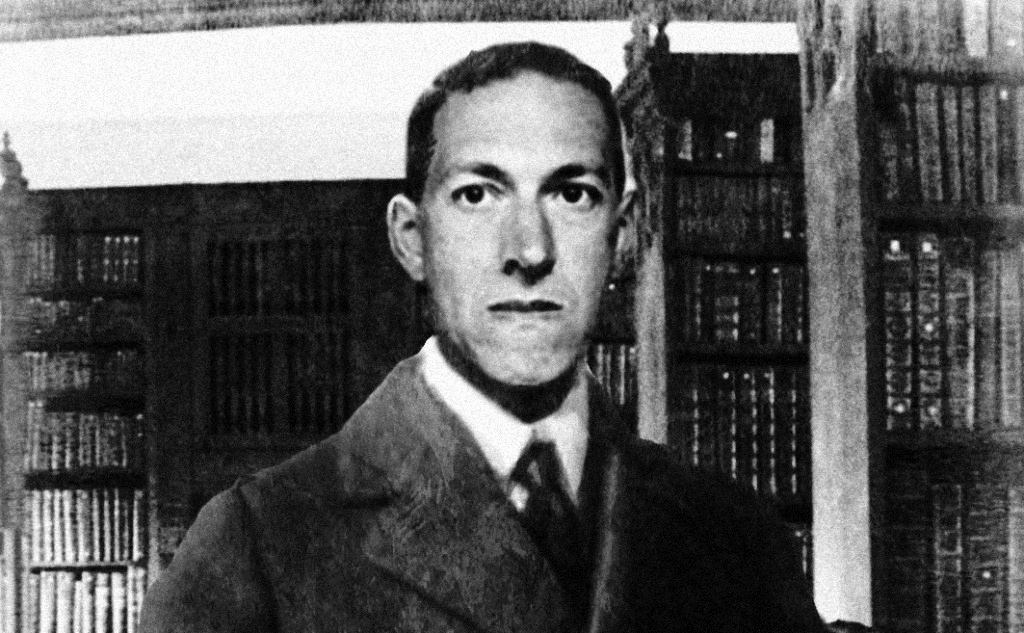

What lies beneath

When you read Poe’s work — or any great literature — it’s as if something is moving beneath the words. It’s like looking out at a deep, gray sea where monsters seethe beneath. You do not see them, per se, but you feel them in your being. So, too, with good writing. As Poe argues, there has to be “some amount of suggestiveness — some under-current, however indefinite, of meaning… which imparts to a work of art so much of that richness”.

The problem is that a lot of writing does not touch this part of our nature. When an author or poet goes too far in describing a thing, or spelling out its themes, then it feels shallow or facile. When a work is only narrating — when it’s little more than a factual account — it is, for Poe, “the very flattest kind.” We need a hint of something terrible and unspoken to get a thrill in the reading.

Let’s go back to “The Raven.” Over the course of the poem, the raven utters a single, incessant “nevermore.” It never changes and never deviates from its one line. And, yet, as the protagonist rails and increasingly challenges the raven, we sense that there is more to the word. There’s something moving beneath.

“Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore!”

The Philosophy of Composition

In his literary essay, “The Philosophy of Composition,” Edgar Allan Poe argues that the point of good art is to evoke “effect” in our intellect, heart, and soul. These are, for Poe, the irreducibly human aspects that we can very rarely explain but often enjoy. But, however hard it might be to explain the feelings we get from reading great literature, the methods and techniques by which to excite them are not. Take one important aspect: length.

For Poe, the length of a written piece will massively affect how it’s enjoyed. Some works — huge novels, for instance — allow for episodic reading. Few will read Robinson Crusoe or Paradise Lost in one sitting, and the authors wrote those works with strategies in mind (often with chapters). With short stories or poems, however, we must allow the “immensely important effect derivable from unity of impression.” It’s only by immersing ourselves in a work, beginning to end, that we can fully engage with the feeling it evokes. Poe’s works are built in a particular way and with such delicate artifice, that if we stop to let the “affairs of the world” interfere, their effect is shattered.

Poe and beauty

Writers are artists, and artists deal in beauty. As Poe writes, “That pleasure, which is at once the most intense, the most elevating, and the most pure is, I believe, found in the contemplation of the beautiful.” Beauty is not bucolic fields and blooming flowers, but it’s anything that evokes those subtle, suggestive, feelings mentioned above. Poe believes that writing is designed to create an effect in the soul of the reader. It’s to embed something that lives beyond the words.

If the purpose and end point of all art is beauty, how can we best create it? Well, most writers specialize in a certain tone. Very few (the geniuses of literature) specialize in many. The trick to becoming a good writer is to find your own tone and exploit that. For Poe, your tone is the route by which you find beauty. Poe recognized that his tone was of sadness. He specialized in that unique kind of Gothic melancholy we enjoy. Others, though, might be better writing on love, or anger, or action. Find your tone, find your road.

Edgar Allan Poe is usually thought an early proponent of “aestheticism.” This is the belief that all art — possibly, all life — ought to be in the service of beauty. As Poe writes, “This thirst belongs to the immortality of Man. It is at once a consequence and an indication of his perennial existence. It is the desire of the moth for the star. It is no mere appreciation of the Beauty before us, but a wild effort to reach the Beauty above.”

Human nature reaches desperately for beauty, and in those brief, blissful moments of its grasping, everything feels right again.

Jonny Thomson runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.