Newton’s apple tree has descendants and clones all over the world

- No, the apple didn’t fall on Newton’s head, but the story checks out — and the tree is still alive.

- You can go visit it at the scientist’s home in Lincolnshire. Or you could find a descendant or clone closer to home.

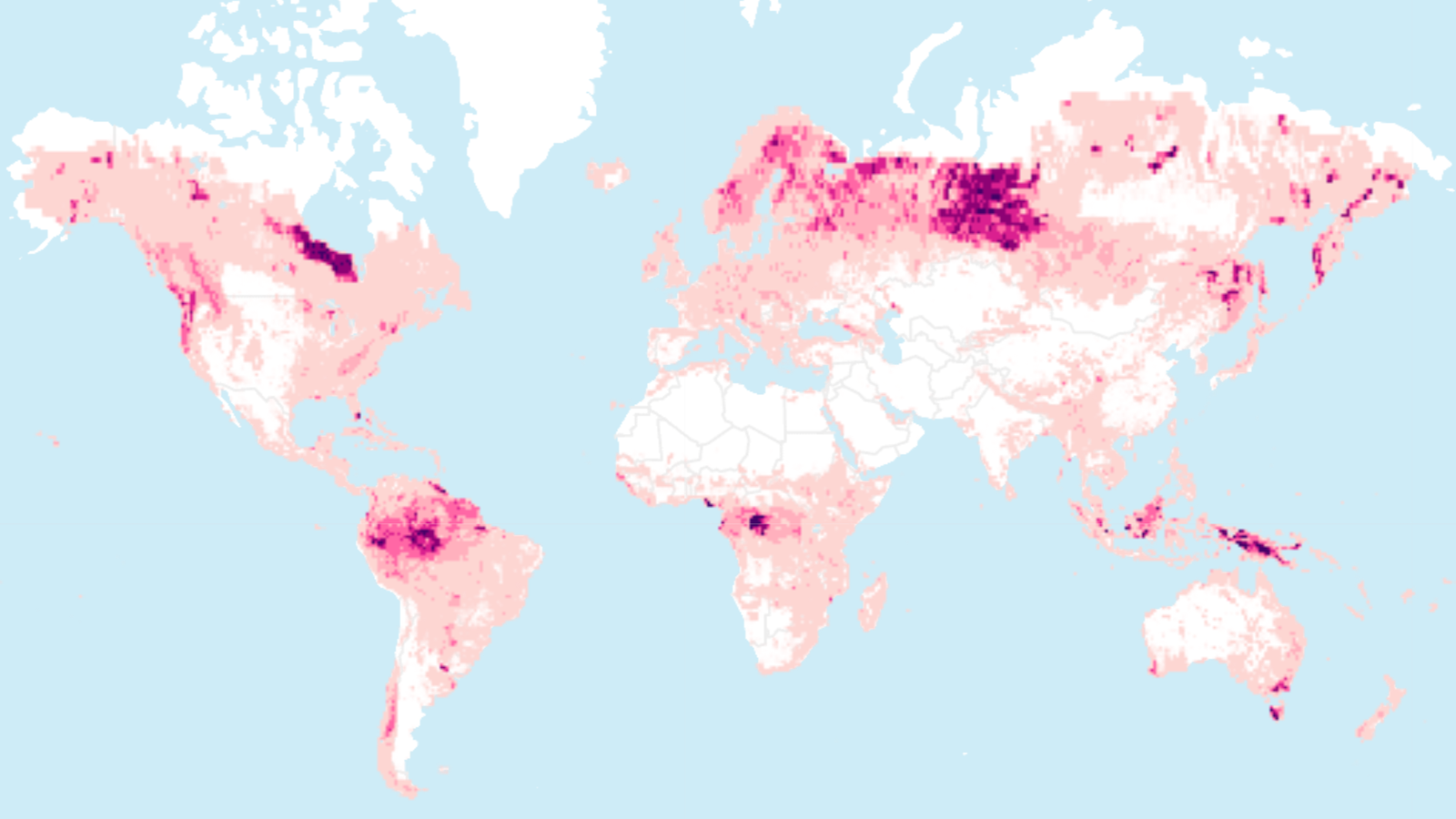

- As this map shows, there are now “gravity trees” on all continents except Antarctica.

It’s gnarly and bent, almost four centuries old, and the most famous tree in the history of science. From that last clue alone, you may have guessed we’re talking about Sir Isaac Newton’s “gravity tree” — because it was an apple falling from its branches that sparked the scientist’s understanding of how gravity works.

Here are three amazing things about that tree:

- Contrary to what you may have heard, the story of Newton and the apple tree is not too good to be true. It’s only embellished a little bit.

- The apple tree is still alive; and yes, we’re pretty sure it’s the right one.

- That tree has parented a worldwide family of saplings. There are now “gravity trees” on every continent except Antarctica, and Atlas Obscura has the map to prove it.

Avoiding Cambridge like the plague

For the origin of the story, let’s go back in time to the summer of 1665. Isaac Newton, then just 23 years old and fresh from obtaining his BA at Cambridge, flees the university to avoid the Great Plague, then killing thousands in London and other English cities. He returns to Woolsthorpe Manor, his ancestral home and birthplace in the relative safety of the Lincolnshire countryside.

While physically homebound, Newton in his mind travels to previously unexplored places. Freed from the strictures of academic life, Newton had the time to think and experiment on his own. This time spent back home was later called his annus mirabilis, or “wonder year.” At Woolsthorpe Manor, Newton laid the groundwork for his theories on calculus and optics, as well as the laws of motion and, yes, gravity — thanks to that apple.

In one version of the story, Newton sits under the apple tree and the fruit hits him squarely on the noggin. That’s too neat. But Newton was inspired by seeing an apple fall. He told that story to plenty of people, including to his niece, who told Voltaire, whose retelling helped popularize the story.

Another source is William Stukely, who in his Memoirs of Sir Isaac Newton’s Life (1752), relates the following conversation with Newton himself, a year before the scientist’s death:

“We went into the garden, & drank thea under the shade of some appletrees, only he, & myself. Amidst other discourse, he told me, he was just in the same situation, as when formerly, the notion of gravitation came into his mind.

“‘Why should that apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground,’ thought he to him self: occasion’d by the fall of an apple, as he sat in a contemplative mood: ‘Why should it not go sideways, or upwards? But constantly to the earths centre? Assuredly, the reason is, that the earth draws it. There must be a drawing power in matter. & the sum of the drawing power in the matter of the earth must be in the earths center, not in any side of the earth.’

“Therefore dos this apple fall perpendicularly, or toward the center. If matter thus draws matter; it must be in proportion of its quantity. Therefore the apple draws the earth, as well as the earth draws the apple.”

A famous specimen of an unpopular species

The King’s School in Grantham, just north of Woolsthorpe Manor, claims the original “gravity tree” was uprooted and replanted in their headmaster’s garden. But Woolsthorpe Manor itself, now managed as a museum, maintains the old specimen in their garden is the right one. That latter claim is supported by various historical sketches, always showing an apple tree where the current one stands. There is no record of any other apple trees at the manor contemporaneous with Newton.

The one, true “gravity tree” likely was planted around 1650, which means it was still fairly young when Newton saw one of its apples fall. It’s a variety known as “Flower of Kent,” producing a bland, mealy variety of apple used mainly for cooking. The species is no longer popular, but this individual one has remained famous.

It did take more than 20 years for that apple to fall, in a manner of speaking: Newton published his law of universal gravitation in his seminal work Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which came out in 1687. From that year onward, as the impact of Newton’s work grew, the tree too acquired a venerated status. After it was blown down in a storm in 1820, its wrecked wood was turned into trinkets, snuff boxes, and by some accounts even a chair (current whereabouts unknown).

Fortunately, the tree was able to be rerooted and, although now clearly past its prime, it continues to be a direct, living link to the work of Sir Isaac Newton.

Zero-gravity tree

In 2012, on the occasion of Queen Elizabeth II’s golden jubilee, the tree was selected as one of 50 Great British Trees. Seeds of the tree were even taken into space for an experiment by the European Space Agency on board the International Space Station on the 2014-15 Principia mission.

Its fame also led to shoots being planted elsewhere. Today, descendants of the original “gravity tree” can be found at universities, botanical gardens, and other scientific institutions across the world.

The Atlas Obscura map shows a number of locations, but it doesn’t mention precise locations or addresses. Below is an overview that we pieced together.

There are several descendants of the “gravity tree” in the UK itself.

- In 1820, a shoot of the original tree was planted in Belton Park, near the tree’s original site. That location is not shown on the map, so the tree may have perished. However, it is from this tree that the Fruit Research Station in East Malling (Kent) obtained material in the 1930s, and it is mainly from this source that the original gravity tree’s descendants have spread across the world.

- There are two “gravity trees” in Cambridge. One is outside the main gate of Trinity College, Newton’s alma mater, just below the window of the room where the scientist himself once resided. The other is at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden.

- There are two locations in the north of England: the University of York and Loughborough University, the university closest to Woolsthorpe.

- There are also two in the south: the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington, Greater London and the Observatory Science Center at Herstmonceux in East Sussex.

There’s just one other location in Europe: at the Technische Hochschule Wildau, south of Berlin, Germany. The U.S. has 14 locations with descendants or clones of the “gravity tree,” more than any other country. Most are at universities:

- University of Nebraska in Lincoln

- University of Wisconsin in Madison

- Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee

- West Virginia University in Morgantown

- William & Mary University in Williamsburg, Virginia

- Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio

- Houghton University in Caneadea, upstate New York

- Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island

- Three in the Boston area: Babson College, MIT, and Tufts University

The three exceptions:

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Gaithersburg, Maryland

- International Park in Washington, DC

- New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx

There are three “gravity tree” locations in Canada:

- In 1968, a “gravity tree” was planted outside the Main Accelerator Building at TRIUMF, Canada’s national particle accelerator center at the University Endowment Lands in Vancouver, British Columbia. The center now manages a grove of seven “gravity trees.”

- York University in Toronto

- National Research Council Canada (NRC-CNRC) in Ottawa.

There are two in South America, both in Argentina:

- Centro Atómico Constituyentes (National Nuclear Research Center) in Buenos Aires

- Instituto Balseiro (a dependency of the National University of Cuyo and of Argentina’s National Atomic Energy Commission) in Bariloche, Rio Negro province

There is one in Africa, at the Babylonstoren farming estate, in the Franschhoek wine valley, in the Western Cape.

Three are in Australia:

- The Clayton campus of Monash University in Melbourne, Victoria

- CSIRO-Parkes Observatory in Parkes, New South Wales

- Orange Agricultural Institute in Orange, New South Wales

There is one in Taiwan, at or near Wuling Farm, in the island’s central highlands, an area popular with tourists for its scenery and its variety of trees.

There are two in China:

- Nankai University in Tianjin

- Beihang University (formerly Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics) in Beijing

There is one in South Korea at the Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science (KRISS) in Daejeon.

And finally, there are three in Japan:

- Keiwagakuen University in Shibata, near Niigata

- Saitama University in Saitama, near Tokyo

- Koishikawa Kōrakuen, a park in Bunkyo, Greater Tokyo

The Atlas Obscura article accompanying the map mentions a “gravity tree” shading the campus of Occidental College in Los Angeles, which is not shown on the map. It’s likely there are other unmapped offshoots of Newton’s famous tree out there. Let us know if you know of any.

Click here for the Atlas Obscura map and article.

Strange Maps #1179

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.