Catacombs of Paris: The city of darkness finds its new raison d’être

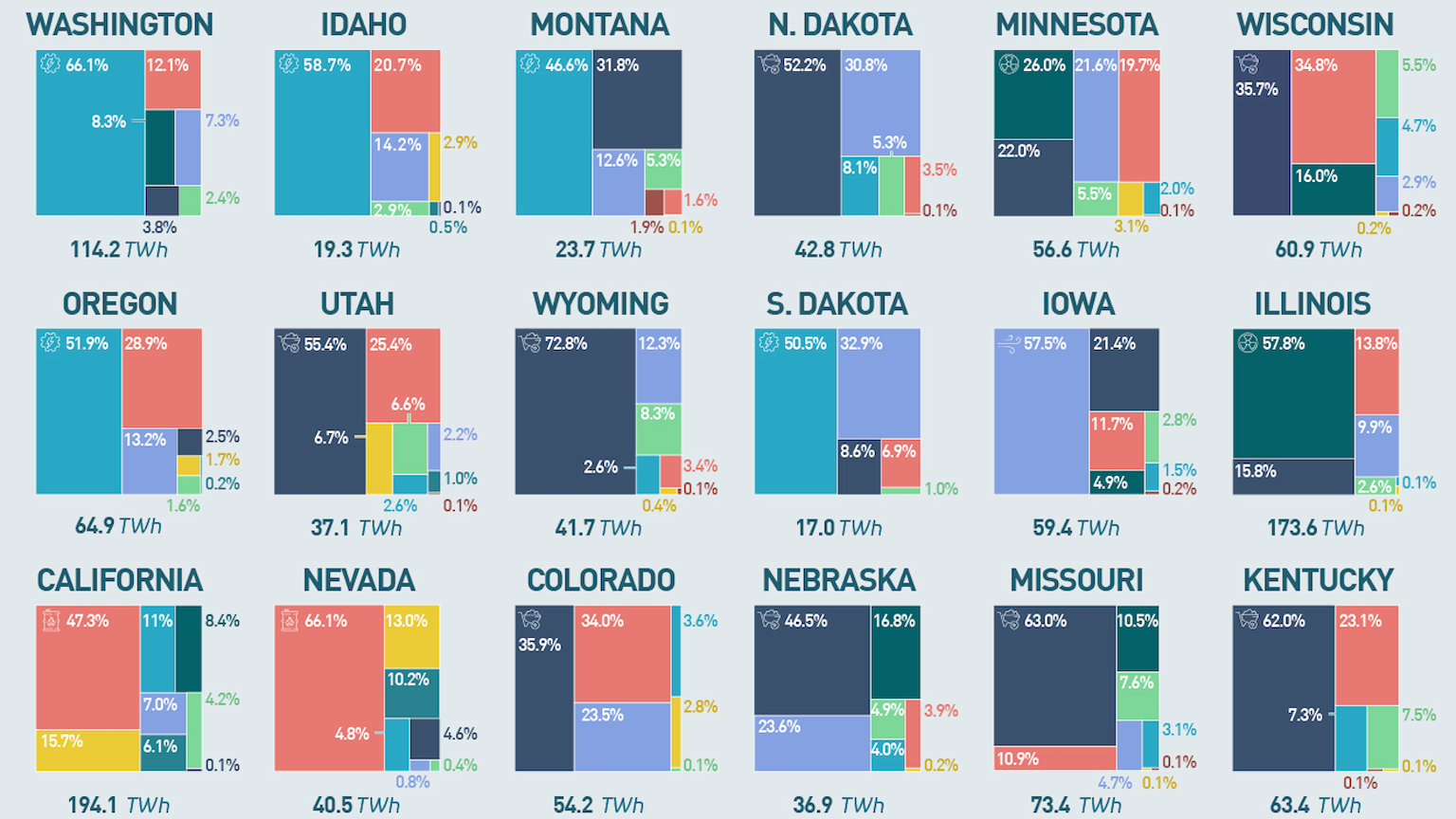

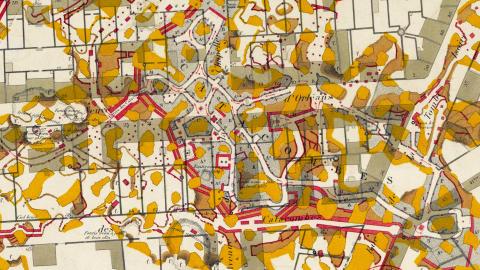

Credit: Inspection Générale des Carrières, 1857 / Public domain

- People have been digging up limestone and gypsum from below Paris since Roman times.

- They left behind a vast network of corridors and galleries, since reused for many purposes — most famously, the Catacombs.

- Soon, the ancient labyrinth may find a new lease of life, providing a sustainable form of air conditioning.

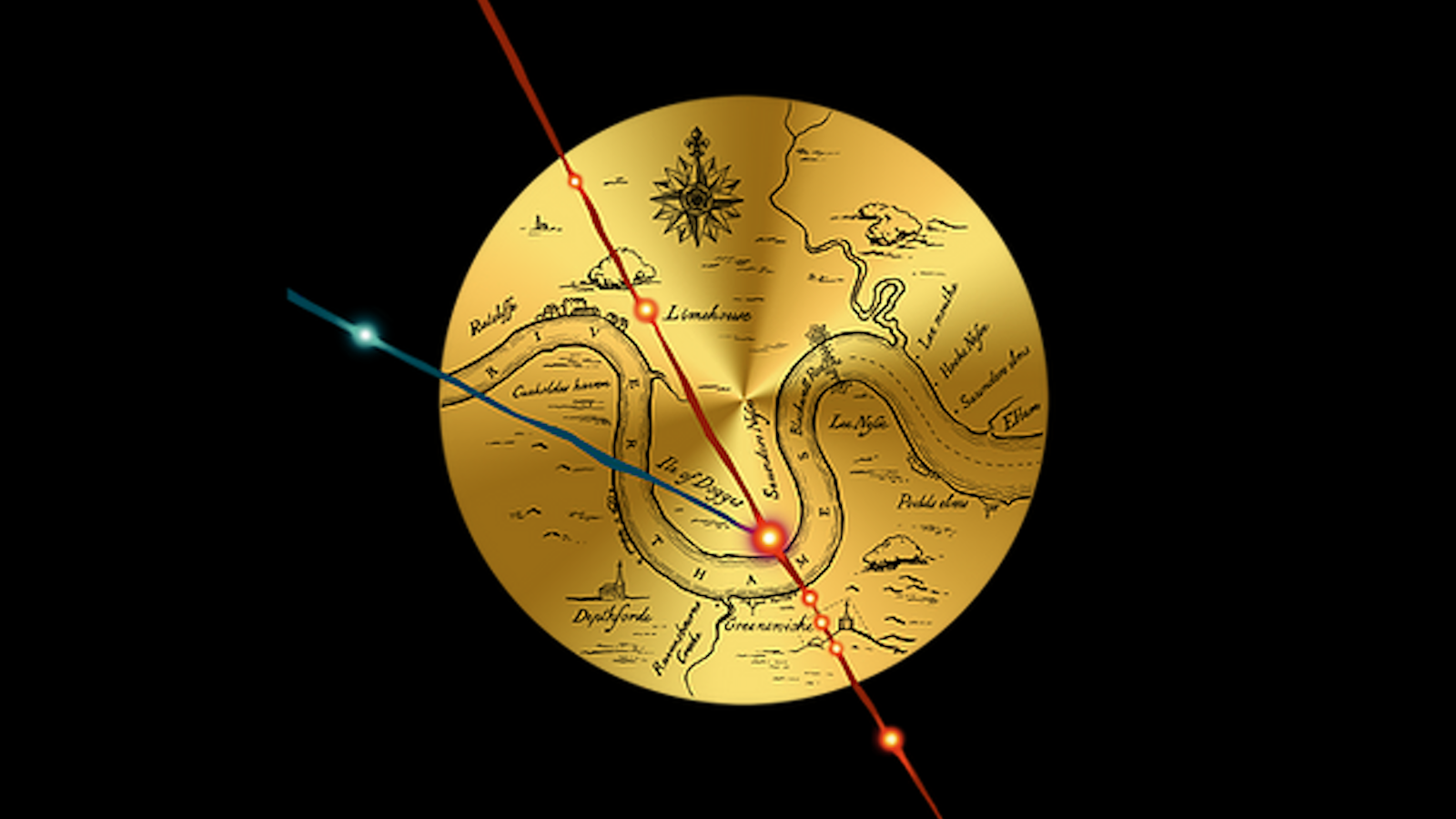

“If you’re brave enough to try, you might be able to catch a train from UnLondon to Parisn’t, or No York, or Helsunki, or Lost Angeles, or Sans Francisco, or Hong Gone, or Romeless.”

China Miéville’s fantasy novel Un Lun Dun is set in an eerie mirror version of London. In it, he hints that other cities have similar doubles. On the list that he offhandedly rattles off, Paris stands out. Because the City of Light really does have a twisted sister. Below Paris Overground is Paris Underground, the City of Darkness.

Most people will have heard of the Catacombs of Paris: subterranean charnel houses for the bones of around six million dead Parisians. They are one of the French capital’s most famous tourist attractions – and undoubtedly its grisliest.

But they constitute only a small fragment of what the locals themselves call les carrières de Paris (“the mines of Paris”), a collection of tunnels and galleries up to 300 km (185 miles) long, most of which are off-limits to the public, yet eagerly explored by so-called cataphiles.

The Grand Réseau Sud (“Great Southern Network”) takes up around 200 km beneath the 5th, 6th, 14th, and 15th arrondissements (administrative districts), all south of the river Seine. Smaller networks run beneath the 12th, 13th, and 16th arrondissements. How did they get there?

Paris stone and plaster of Paris

It all starts with geology. Sediments left behind by ancient seas created large deposits of limestone in the south of the city, mostly south of the Seine; and gypsum in the north, particularly in the hills of Montmartre and Ménilmontant. Highly sought after as building materials, both have been mined since Roman times.

The limestone is also known as Lutetian limestone (Lutetia is the Latin name for ancient Paris) or simply “Paris stone.” It has been used for many famous Paris landmarks, including the Louvre and the grand buildings erected during Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s large-scale remodelling of the city in the mid-19th century. The stone’s warm, yellowish color provides visual unity and a bright elegance to the city.

The fine-powdered gypsum of northern Paris, used for making quick-setting plaster, was so famed for its quality that “plaster of Paris” is still used as a term of distinction. However, as gypsum is very soluble in water, the underground cavities left by its extraction were extremely vulnerable to collapse.

In previous centuries, a road would occasionally open up to swallow a chariot, or even a whole house would disappear down a sinkhole. In 1778, a catastrophic subsidence in Ménilmontant killed seven. That’s why the Montmartre gypsum quarries were dynamited rather than just left as they were. The remaining gypsum caves were to be filled up with concrete.

The official body governing Paris down below is the Inspection Générale des Carrières(IGC), founded in the late 1770s by King Louis XVI. The IGC was tasked with mapping and, where needed, propping up the current and ancient (and sometimes forgotten) mining corridors and galleries hiding beneath Paris.

A delightful hiding place

Also around that time, the dead of Paris were getting in the way of the living. At the end of the 18th century, their final destination consisted of about 200 small cemeteries, scattered throughout the city — all bursting at the seams, so to speak. There was no room to bury the newly dead, and the previously departed were fouling up both the water and air around their respective churchyards.

Something radical had to happen. And it did. From 1785 until 1814, the smaller cemeteries were emptied of their bones, which were transported with full funerary pomp to their final resting place in the ancient limestone quarries at Tombe-Issoire. Three large and modern cemeteries were opened to receive the remains of subsequent generations of Parisians: Montparnasse, Père-Lachaise, and Passy.

The six million dead Parisians in the Catacombs, from all corners of the capital and across many centuries, together form the world’s largest necropolis — their now anonymized skulls and bones methodically stacked, occasionally into whimsical patterns. The Catacombs are fashioned into a memorial to the brevity of life. The message above the entrance reads: Arrête! C’est ici l’empire de la Mort. (“Halt! This is the empire of Death.”)

That has not stopped the Catacombs, accessible via a side door to a classicist building on the Avenue du Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy, making just about every Top 20 list of things to see in Paris.

An underground economy

However, while the Catacombs certainly are the most famous part of the centuries-old network beneath Paris, and in non-pandemic times draw thousands of tourists each day, they constitute just 1.7 km (1 mile) of the 300-km (185-mile) tunneling total.

Subterranean Paris wasn’t just used for mining and storing dead people. In the 17th century, Carthusian monks converted the ancient quarries under their monastery into distilleries for the green or yellow liqueur that still carries their name, chartreuse.

Because the mines generally keep a constant cool temperature of around 15° C (60° F), they were also ideal for brewing beer, as happened on a large scale from the end of the 17th century until well into the 20th century. Several caves were dug especially for establishing breweries, and not just because of the ambient temperature: going underground allowed brewers to remain close to their customers without having to pay a premium for real estate up top.

At the end of the 19th century, the underground breweries of the 14th arrondissement alone produced more than a million hectoliters (22 million gallons) per year. One of the most famous of Paris’ underground breweries, Dumesnil, stayed in operation until the late 1960s.

In that decade, the network of corridors and galleries south of the Seine, long since abandoned by miners, became the unofficial playground for the young people of Paris. They explored the fantastical world beneath their feet, in some cases via entry points located in their very schools. Fascinated, these cataphiles (“catacomb lovers”) read up on old books, explored the subterranean labyrinth, and drew up schematics that were passed around among fellow initiates as reverently as treasure maps.

As Robert Macfarlane writes in Underland, Paris-beneath-their-feet became “a place where people might slip into different identities, assume new ways of being and relating, become fluid and wild in ways that are constrained on the surface.”

Some larger caves turned into notorious party zones: a 7-meter-tall gallery below the Val-de-Grâce hospital is widely known as “Salle Z.” Over the last few decades, various other locations in subterranean Paris have hosted jazz and rock concerts and rave parties — like no other city, Paris really has an “underground music scene.”

Cataphiles vs. cataphobes

With popularity came increased reports of nuisance and crime — the tunnels provided easy access to telephone cables, which were stolen for the resale value of their copper.

The general public’s “discovery” of the underground network led the city of Paris to officially interdict all access by non-authorized persons. That decree dates back to 1955, but the “underground police” have an understanding with seasoned cataphiles. Their main targets are so-called tourists, who by their lack of knowledge expose themselves to risk of injuries or worse, and degrade their surroundings, often leaving loads of litter in their wake.

The understanding does not extend to the IGC. Unlike in the 19th century, when weak cavities were shored up by purpose-built pillars, the policy now is to inject concrete to fill up endangered spaces — thus progressively blocking off parts of the network. That procedure has also been used to separate the Catacombs to prevent “infiltration” of the site by cataphiles.

The cataphiles, however, are fighting back. In a game of cat and mouse with the authorities, they are reopening blocked passages and creating chatières (“cat flaps”) through which they can squeeze into chambers no longer accessible via other underground corridors.

Catacomb climate control

Alone against the unstoppable tide of concrete, the amateurs of Underground Paris would be helpless. But the fight against climate change may turn the subterranean labyrinths from a liability into an asset — and the City of Paris into an ally.

The UN’s 2015 Climate Plan — concluded in Paris, by the way — requires the world to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 75 percent by 2050. And Paris itself wants to be Europe’s greenest city by 2030. More sustainable climate control of our living spaces would be a great help toward both targets. A lot of energy is spent heating houses in winter and cooling them in summer.

This is where the constant temperature of the Parisian tunnels comes in. It’s not just good for brewing beer; it’s a source of geothermal energy, says Fieldwork, an architectural firm based in Paris. It can be used to temper temperatures, helping to cool houses in summer and warming them in winter.

One catch for the cataphiles: it also works when the underground cavities are filled up with concrete. So perhaps one day, Paris Underground, fully filled up with concrete, will completely fall off the map, reducing the city’s formerly real doppelgänger into an air conditioning unit.

Strange Maps #1083

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.