Scientists discover how the rampant ‘cat poop parasite’ controls cells

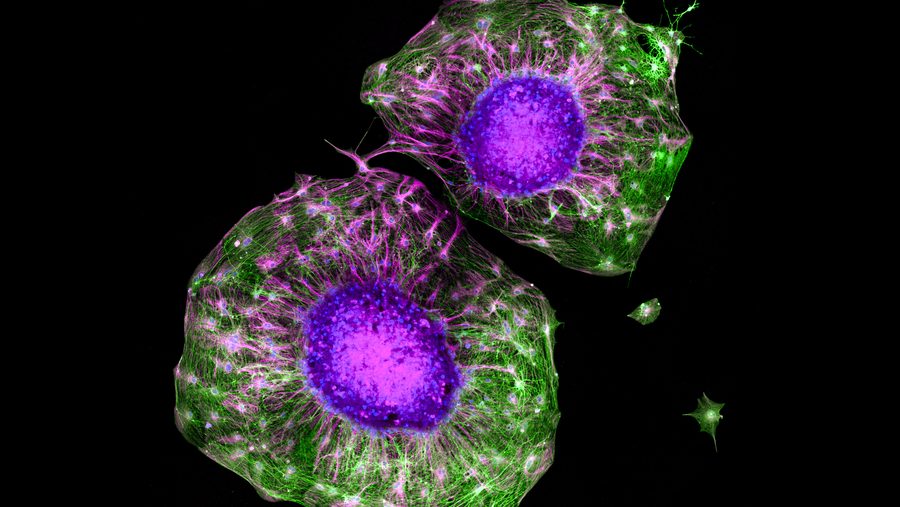

Credits: Left: Ke Hu and John M. Murray via Wikimedia CC BY 4.0 / Right: Harry Cunningham @harry.digital from Pexels

- Toxoplasma gondii is a parasite that can cause behavioral changes and major health problems in humans.

- A new study suggests its unique way of spreading in the body can be stopped.

- The findings are currently limited to mice, but may one day result in new treatments for people.

The archetype of the crazy cat lady is embedded in our culture. It’s also a notion based on some truth, with several well-known people keeping more than a few cats for company. It is also known that a parasite often transmitted from humans to cats, Toxoplasma gondii, is associated with a variety of psychological problems, including schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. That gives the crazy cat owner trope a tragically factual basis.

However, a new study of the widespread parasite offers new insights into the parasite’s strange capacities to use cells as transportation. This breakthrough provides a chance at more effective treatments.

The Cat Parasite Possibly Manipulating Your Behavior — And Other Parasitic Wonders

Toxoplasma gondii is a strange parasite. Capable of infecting most warm-blooded animals, it is best known for its presence in cats. Felines typically get the disease by eating something else that has it, like a bird or a mouse. When rodents are infected, the fear center of their brain gets turned down, they lose their aversion to cat odors and are much more active. These behavior changes are thought to make it more likely that a cat eats them.

People can either get Toxoplasma infections from interacting with contaminated cat litter or eating undercooked meat from something that was infected. The number of humans infected is estimated to be anywhere from 30 to 50 percent of the global population, with fluctuations between countries.

In people without compromised immune systems, the disease is latent and generally asymptomatic—though some recent studies suggest subtle shifts in behavior even in these cases. In persons with compromised immune systems, the infection may become acute and cause seizures, vision problems, and confusion, among other issues.

It can be challenging to treat these infections due to the number of cells they are capable of infecting and its habit of spreading through the body quickly. Study lead author Dr. Leonardo Augusto explained this problem to Phys.org:

“One of the key problems in battling an infection like Toxoplasma is controlling its spread to other parts of the body. Upon ingestion of the parasite, it makes its way into immune cells and causes them to move—a behavior called hypermigratory activity. How these parasites cause their infected cells to start migrating is largely unknown.”

This study looked at how Toxoplasma works in mice cells. Under normal conditions, certain cells undergoing stress can move to other places in the body after a protein called IRE1 is activated. Toxoplasma can activate this protein in cells that it has infected, allowing it to move around the body using the cells as a ride. In short order, it can arrive at new organs, which it then infects.

In this study, the scientists were able to deplete the supply of IRE1 in a mouse cell infected with Toxoplasma, which severely reduced cellular movement. The Toxoplasma the cells were infected with was then unable to spread to other parts of the body.

If the takeaways from this study are as useful in humans as they are in mice, it opens up routes for new treatments that may prevent the spread of the infection.