The future of the Amazon may depend on tapir poop

Image source: slowmotiongli/Shutterstock

- Tapirs produce towering piles of feces full of large-tree seeds other animal can’t pass.

- Stashing tasty fecal morsels for later, dung beetles bury the seeds.

- Tapirs prefer burned-out areas, making them ideal re-foresters.

The Amazon rainforest has been in trouble for some time. In the last 40 years, more than 18% of Brazil’s rainforest, for example, has been decimated by logging, farming, mining, and cattle ranching. That’s an area about the size of California. If it isn’t deliberate deforestation for commercial purposes, it’s fires. Last years’s unprecedented rainforest conflagrations, 85% more severe than the previous year’s, were absolutely devastating, burning away some 10.123 square kilometers of forest. This year looks worse — in the first four months of 2020 alone, 1,202 square kilometers have been incinerated.

Often poking their way though the charred remains are trunk-nosed lowland tapirs (Tapirus terrestris), and that’s a great thing. “Tapirs in Brazil are known as the gardeners of the forests,” says ecologist Lucas Paolucci of Amazon Environmental Research Institute in Brazil. They’re prodigious defecators whose feces is packed with a remarkable assortment of seeds from the plants they ingest. Paolucci has great hopes for the role that tapirs, along with dung beetles, their partners in grime, can play in reforesting the Amazon. It’s something they’re already doing on their own.

Tapir poop in a zooImage source: Kulmalukko/Wikimedia

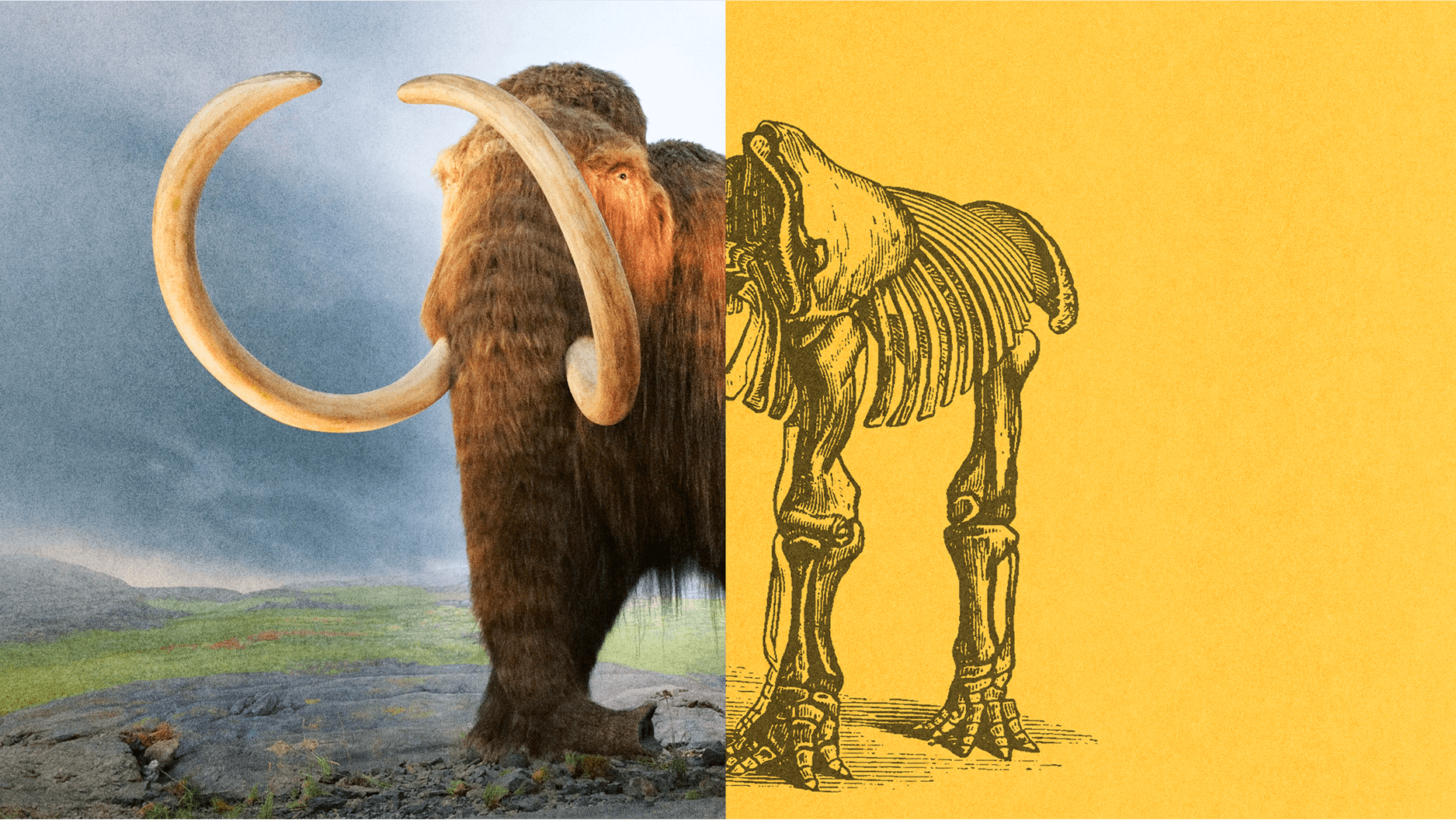

The tapir is South America’s largest native mammal, looking a bit like a pig with a trunk. It’s actually more closely related to a horse or rhinoceros, and is believed to have been around for tens of millions of years.

Paolucci found tapir’s massive mounds of dung — “bigger than my head” — hard to miss. Inside each pile is a treasure trove of seeds including those from large, carbon-storing trees that are just too big to pass through the digestive tracts of smaller mammals. This makes them invaluable disseminators of exactly the sort of trees needed to rebuild a forest.

Tapirs seem to prefer the burned-out areas in which they’re most needed, too. In 2016, Paolucci joined other researchers in studying the type of areas tapirs like to frequent. In eastern Mato Grasso, they tracked the goings-on in three plots of forest land. Two of these plots had been subjected to controlled burns from 2004 to 2010. One of then was burned every year, while the other was torched every three. The third plot was left unburned as a control.

Patrolling the plots, the researchers recorded the locations of 163 tapir-dung piles, confirming their source with camera-trap recordings of the perpetrators. The tapirs, it turned out, spend much more time in the burned out forest plots than the untouched one. Paolluccis suggests they may prefer the warm sunshine in areas not covered by forest canopy.

When the researchers extracted and counted up the seeds in those piles, an impressive array was cataloged: 129,204 seeds representing 24 plant species. Biodiversity writ in poo.

Image source: Jasper_Lensselink_Photography/Shutterstock

Seeing the tapirs’ deposits leading to widespread new growth meant that something, or someone, else, had been spreading them out for planting: Dung beetles, of the superfamily Scarabaeoidea. Paolucci conducted an experiment that confirmed that dung beetles break off piles of tapir dung, roll them away, and bury them for later munching. The seeds in their snacks are in effect planted where they can grow.

Early last year, Paolucci retrieved 20 kilograms of tapir poop from the Amazon, breaking it apart into 700-gram clumps. He returned these clumps to the Amazon after stuffing each one with plastic pellets to serve as as dummy seeds. After 24 hours, Paolucci collected the clumps and counted the pellets gone missing, a simple way to calculate the number of new plants the dung beetles had planted that day. He hopes to publish the details of his study next year.

While tapirs and their dung-beetle buddies clearly can help reforest the Amazon, they, like everything else trying to live in the rainforest region, are themselves endangered by the raging forest fires. If they’re lost, going with them will be a fantastic means of spreading large-tree seeds through the region.