The ancient architecture that defies earthquakes

The powerful 7.8 magnitude earthquake that struck Turkey and Syria on February 6 killed almost 50,000 people, most of whom died under rubble.

The tragedy falls in a decades-long history of outsized death and destruction from recent earthquakes: The 1999 İzmit earthquake near Istanbul killed at least 17,000 people; the 2001 Gujarat earthquake in India killed upward of 20,000; and the 2005 Kashmir earthquake in Pakistan killed more than 87,000 and left some 3.5 million people unhoused. The immediate cause of the human tragedies was not the shaking ground itself, but the buildings people were in, most of which were constructed of reinforced cement concrete, a relatively quick and cheap building method.

Earthquakes don’t have to be so deadly, say scholars who study this issue.1 Many traditional buildings have stood the test of time in regions that have endured high seismic activity for centuries.

In Japan, people had long built earthquake-resistant structures mostly from wood. But a different tradition shows that even stone buildings can withstand vigorous shaking—if they are built with clever physics and architectural adaptations, honed over the centuries.

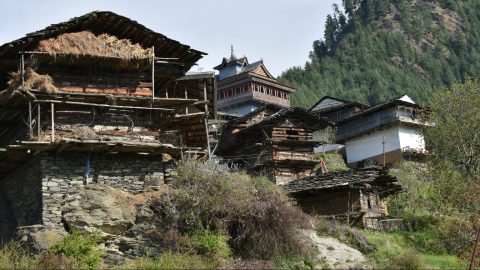

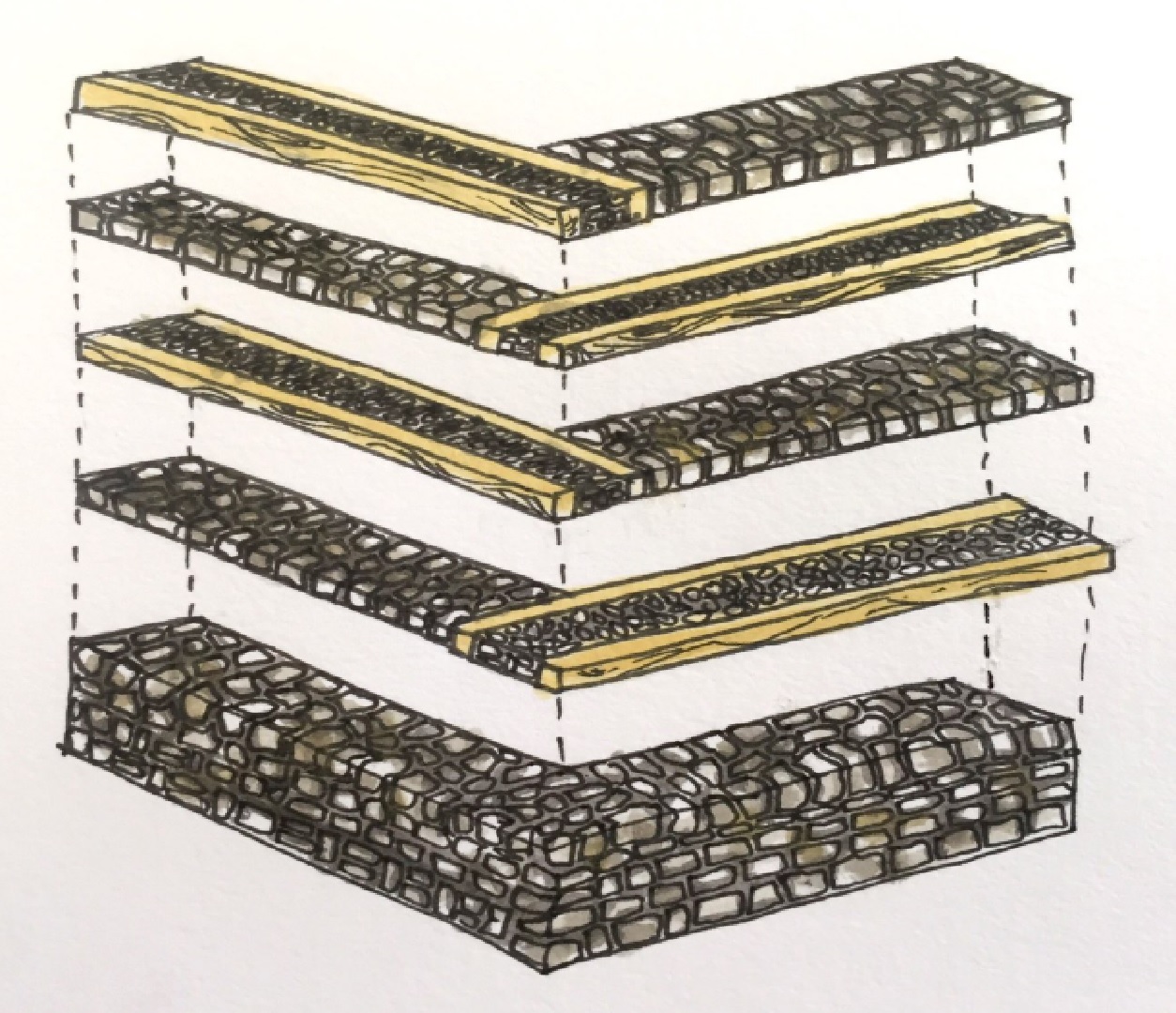

In the mountainous region of Himachal Pradesh in India, near where the Indian Plate is colliding with the Eurasian Plate, many structures built in the kath kuni style have survived at least a century of earthquakes. In this traditional building method, the name, which translates to “wood corner,” in part explains the method: Wood is laced with layers of stone, resulting in improbably sturdy multi-story buildings.

The gravitational force of the structure itself holds the stones in place.

It is one of several ancient techniques that trace fault lines across Asia. The foundations for the timber lacing system of architecture may have originally been laid in Istanbul around the fifth century. Stone masonry and wood-beam construction can still be seen in Nepal as well as in the traditions of Kashmiri Taq and Dhajji Dewari and Pakistani Bhatar. Even Turkey has a long tradition of similar construction methods. Despite their ancient origins, this model of construction has mostly fared better over centuries than much of the contemporary building across the continent’s many active seismic zones.

Built along the natural contours of the hills, kath kuni buildings typically get their signature corners from giant deodar cedars, which grow upward of 150 feet tall and 9 feet across in the Himalayas. These wooden beams layer between dry stones, which create walls. A single wooden “nail” joins the beams where they come together.

As the ponderous-looking structures rise vertically, usually up to two to three stories, the heavy stone masonry reduces, giving way to more wood. The overhanging roof typically has slate shingles resting on wooden beams. “The structure is like a body with heavy base, the projecting wooden balconies are limbs, and the heavy slate roof is like a head adding stability to the structure,” says Jay Thakkar, a faculty member at the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology University in Ahmedabad, India, who co-authored the book Prathaa: Kath-kuni Architecture of Himachal Pradesh.

The buildings stand free of any mortar or metal, which makes them more capable of shifting and flexing along with torques in the ground. This brilliance of mobility even continues underground. They are built over a trench at least a few feet deep filled with loose stone pieces that works as a flexible plinth. While a building constructed out of what seems almost like rubble to begin with might seem a strange defense against earthquake damage, it works. The gravitational force of the structure itself holds the stones in place.

“Unlike the cement brick wall, which becomes a single solid mass, the dry stone masonry is flexible,” Thakkar says. “Staggered joints allow the external forces like tremors of earthquakes to be dispersed through the masonry thus preventing cracks in walls.” He adds, “The wooden pin at the corner joint of two beams also allows movement. So when an earthquake hits, the structure sways and shakes but doesn’t collapse.”

Despite centuries of visible evidence of these traditional structures’ soundness, people have turned more and more to reinforced concrete construction. By the early and mid-20th century, reinforced concrete was taking hold across Asia and quickly gained popularity because of its substantially lower labor costs. As such, it became the default method for much new construction, including any government-funded buildings. But “for reinforced concrete construction, poor quality construction in this material has so often produced buildings that are more dangerous than the traditional unreinforced masonry buildings they replaced, despite the promises made about concrete buildings,” wrote a team of researchers studying traditional timber and masonry buildings in Turkey.1

Indian architect Rahul Bhushan, who works toward reviving traditional construction methods in the Himachal Pradesh region, says, “the kath kuni style of architecture, while being still used in temple construction, had kind of paused for other structures due to the advent of reinforced concrete as building material. As a result, gradually, the traditional expertise declined.”

Bhushan’s group, which is called NORTH, has been training masons and construction laborers in traditional methods. Their workshops are generating renewed attention for earthquake resistant architecture rooted in these ancient techniques. He is hopeful this momentum will continue. “People are gradually showing interest toward kath kuni and other traditional constructions like dhajji dewari again.”

The onus now lies on practicing architects and researchers to convince government agencies to support the traditional system of construction, which could help contain destruction the next time an earthquake rocks the region, which, as the geologic plates continue to collide, is only a matter of time.

Shoma Abhyankar is an independent writer based in India. She writes on travel, culture, environment, and architecture. She is on Twitter at @throbbingmind.

References

1. Gülkan, P. & Langenbach, R. The earthquake resistance of timber and masonry dwellings in Turkey. 13th World Conference on Earthquakes Engineering (2004).

This article originally appeared on Nautilus, a science and culture magazine for curious readers. Sign up for the Nautilus newsletter.