Ancient Greek and Roman statues originally were painted. This is what they should look like

- Today, Greek and Roman statues appear as white as the marble they are made of.

- Back in antiquity, however, many sculptures were covered in bright paints and patterns.

- This relatively new revelation, long ignored, reframes our understanding of ancient art.

During the early 1980s, a German archaeologist named Vinzenz Brinkmann was scrutinizing the surface of an ancient Greek sculpture in search of tool marks. Although he never found what he was looking for — like the painters of the Italian Renaissance, Greek sculptors were so skilled they hardly left a trace of their own handiwork — he did discover traces of something else: paint.

Almost exactly a century before that, an American art critic named Russell Sturgis made a similar discovery when he traveled to Athens to attend the excavation of an ancient statue near the Acropolis. To his surprise, the statue didn’t look anything like the ones displayed in museums. Whereas those are as white as the marble they are made of, this one was covered in brittle dabs of red, black, and green pigment.

Sturgis and Brinkmann both stumbled upon a truth which, even after all these years, has yet to become common knowledge outside of academic circles: that ancient Greek statues originally were painted with a palette as bright and colorful as Vincent van Gogh’s, and that their modern, monochromatic appearance, however iconic, is essentially an accident caused by the passage of time.

Emperors and harlequins

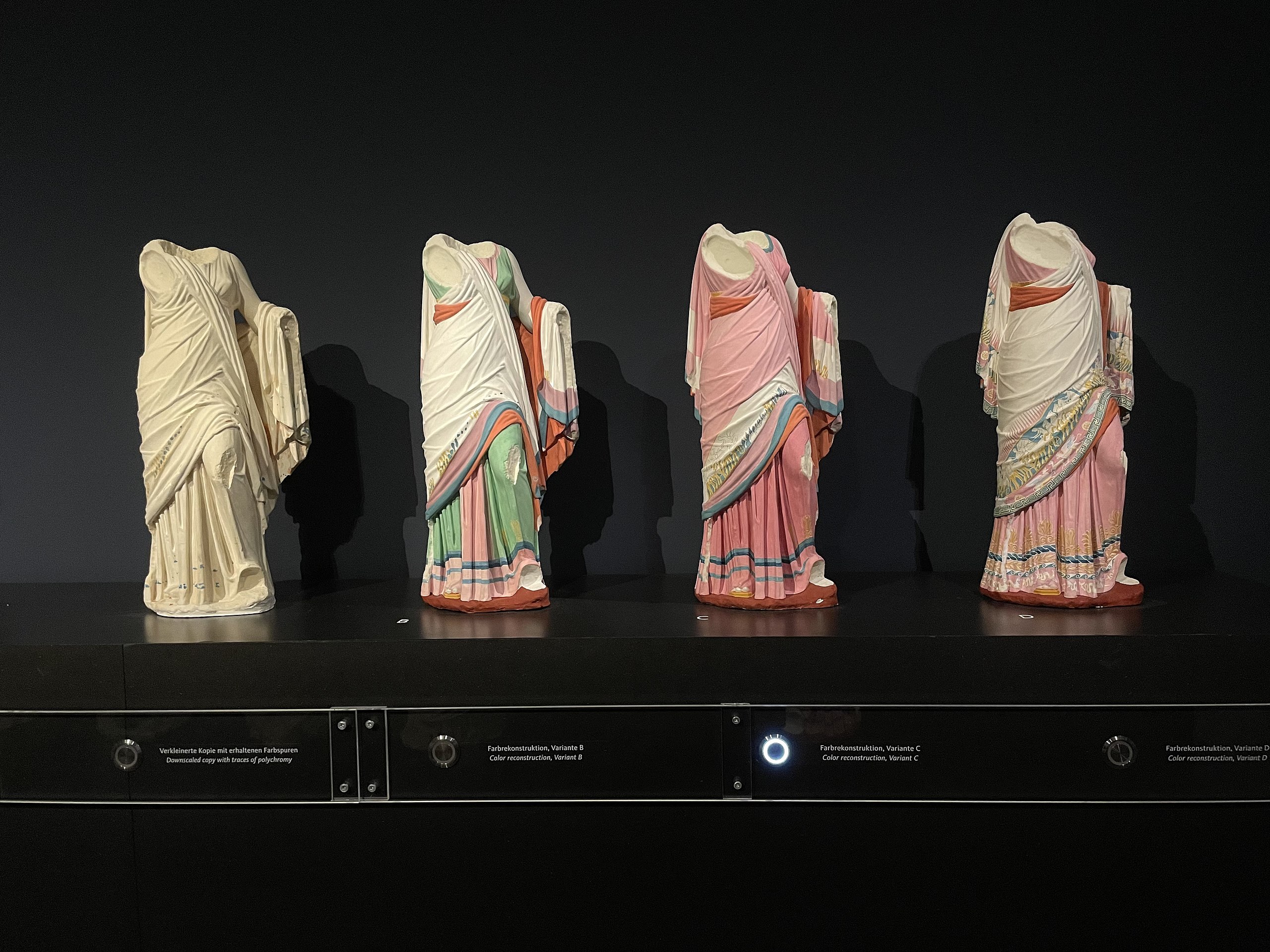

Sampling pigment residue, Brinkmann created copies of Greek and Roman sculptures in their initial color scheme. His traveling exhibit, Gods in Color, came as a shock to a world used to seeing ancient Greece and Rome in black and white. It was also popular, running for 12 years before paving the way for similar shows like the MET’s Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color, which opened in 2022.

In color, even the most well-known Greek statues become almost unrecognizable. Pale bodies acquire an array of mostly dark skin tones. Austere robes display bold patterns reminiscent of medieval harlequins. A statue of a lion that was placed in front of a Corinthian tomb during the sixth century BC used to have an ochre body and azurite mane before centuries-long exposure to the elements rendered it a dull, uniform white.

This playfulness extends to sculptures made from metal, too. Bronze statues were accentuated with copper lips, nipples, and swirls of pubic hair, touches that an article from the New Yorker says added a “disarming fleshiness” to them. Some of these Greek statues, which had shimmering gemstones for pupils, also used different metals to recreate blood dripping from open wounds.

Although these color reconstructions have been mostly well-received, there is an ongoing debate regarding their historical accuracy. Stanford University art historian Fabio Barry, who once described a repainted statue of the Roman Emperor Augustus at the Vatican as “a cross-dresser trying to hail a taxi,” thinks that research projects like Brinkmann’s have turned into something of a market ploy. As told to the New Yorker:

“The various scholars reconstructing the polychromy of statuary always seemed to resort to the most saturated hue of the color they had detected, and I suspected that they even took a sort of iconoclastic pride in this — that the traditional idea of all-whiteness was so cherished that they were going to really make their point that it was colorful.”

Whitewashing antiquity

For centuries, European scholars assumed Greek and Roman sculptors had left their work bare for a reason. The absence of color, far from being circumstantial, was interpreted as a sign of creative restraint, an emphasis on form over decoration, and a general rejection of the “bad taste” that characterized the more colorful artwork to come out of other regions of the ancient world, like Egypt.

Needless to say, European scholars also appreciated the apparent whiteness of ancient sculpture because they themselves were white. At best, this erroneous connection cultivated casual racism. “The whiter the body, the more beautiful it is,” Johann Winckelmann, a German art historian, declared in the 1800s, adding that while “color contributes to beauty,” it shouldn’t be mistaken for the real thing.

At worst, it served as one justification for Europe’s imperial aspirations. As the continent entered its colonial era, arguments for the superiority of Greco-Roman art increasingly came to double as arguments for the supremacy of the Western civilizations that had laid claim to antiquity’s cultural and political inheritance — a line of thinking that reached its zenith in the run-up to the Second World War.

This fantasy of Greco-Roman whiteness reinforced itself. Each time a rare example of a statue with intact color was discovered, experts argued it had to have been made by a different and, in their eyes, inferior culture, such as the pre-Roman Etruscans. Whenever dealers got their hands on such statues, they would scrub them until the pigment had been removed, making them more valuable on the market.

Although seeing Greek and Roman sculptures in color for the first time can be disorienting, the experience serves as an important reminder that the ancient world was much more multiethnic than commonly believed. Greece and Rome were not just cultural melting pots, but there is even evidence that the Greeks — in contrast to Winckelmann’s assertion — saw darker skin tones as more beautiful than lighter ones.