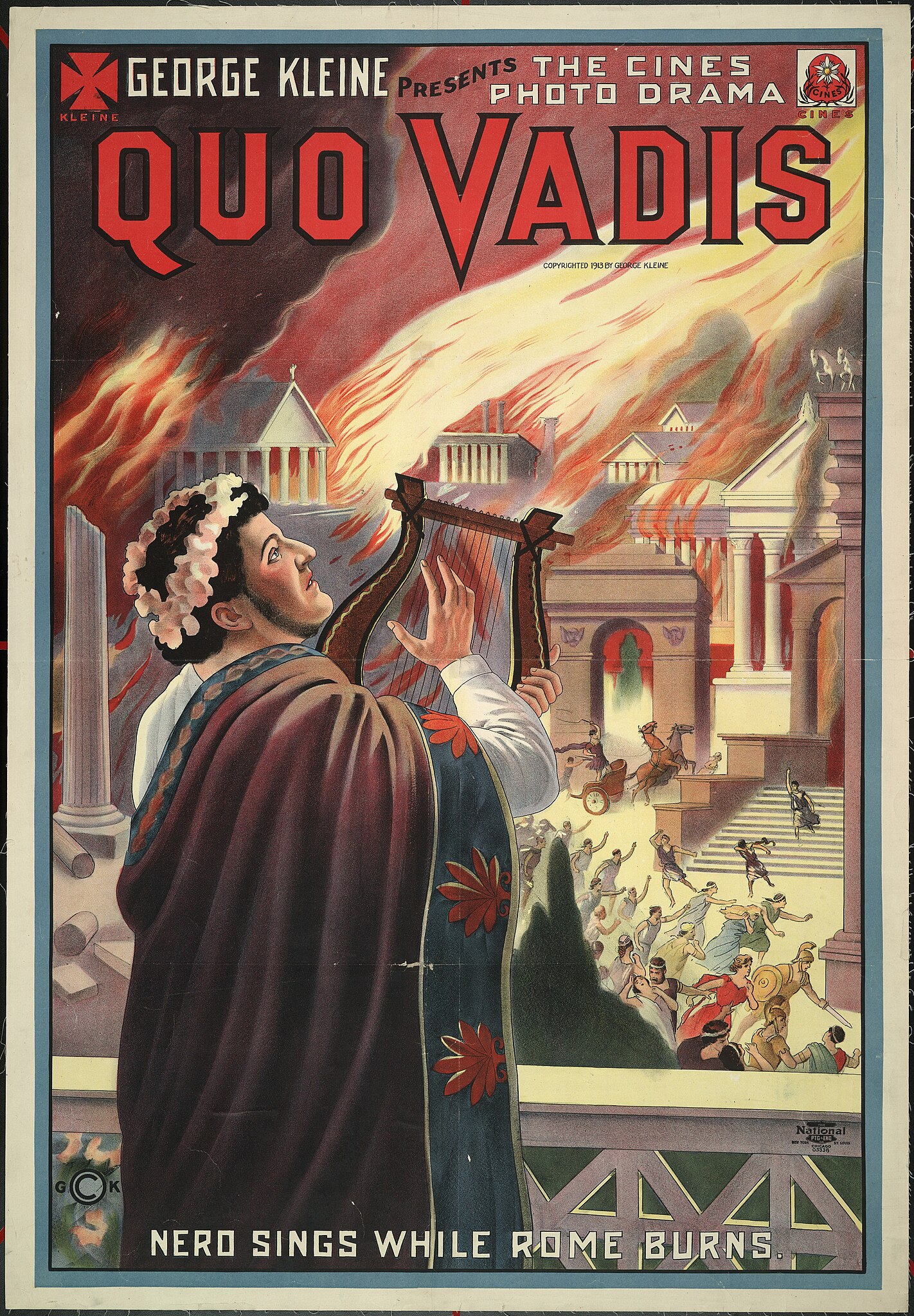

Did Emperor Nero really play the fiddle as Rome burned?

- Nero killed his own family members and played music while Rome burned.

- At least, that is what ancient writers like Suetonius would have us believe.

- Some contemporary historians argue Nero’s infamy is rooted in propaganda and that he wasn’t as evil as commonly thought.

Making way for a Four Seasons hotel next to the Vatican City, archaeologists and construction workers recently stumbled upon the ruins of a theater from the 1st century AD. According to project leader Renato Sebastiani, “The richness of the materials used, the marbles, the stuccos decorated with gold leaf,” suggesting that this theater was made for and used by none other than the infamous Roman Emperor Nero.

If ancient sources are to be believed, spending an evening at Nero’s theater would have been anything but entertaining. Flaunting Roman traditions, the emperor didn’t just watch the shows — he performed in them. And because he fancied himself a talented artist, he expected standing ovations whenever he sang a song or recited a poem. In his Lives of the Twelve Caesars, the historian Suetonius writes that when Nero took to the stage, “[N]o one was allowed to leave the theatre even for the most urgent reasons.”

“And so it is said that some women gave birth to children there, while many who were worn out with listening and applauding, secretly leaped from the wall, since the gates at the entrance were closed, or feigned death and were carried out as if for burial.”

Outside of the theater, Nero was no less insufferable. Ascending to the throne at age 16 after his mother Agrippina the Younger allegedly poisoned his predecessor Claudius, a paranoid Nero is said to have staged the murder of both his brother Britannicus and, later, Agrippina herself. He killed his first wife Octavia so he could marry his second wife, Poppea, whom he ended up beating to death in an argument. Regretting this outburst, he then castrated a young boy who happened to look like her, dressing him in her clothes and addressing him as his “queen.” Nero also persecuted innocent Christians who refused to recognize his self-proclaimed divinity, nearly bankrupted the empire with lavish banquets, and — most famously — “played the fiddle” during a fire that destroyed two-thirds of Rome.

In light of such damning biographical details, several scholars wonder if Nero was truly as horrible a person and ruler as we have been led to believe. It’s an important question to ask, not in the least because Roman history survives primarily through the accounts of writers like Suetonius, who himself was prone to exaggeration.

The fiddler that never was

“I am not setting out here to rehabilitate Nero as a blameless man,” Thorsten Opper, a curator in the British Museum’s Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, told The Art Newspaper in 2021. “But I have come to the conclusion that almost every single thing we think we know about him is wrong.” At the time, Opper had just finished working on an exhibit titled “Nero: Behind the Myth,” which urged visitors to take a more critical look at the emperor’s bad reputation.

While Suetonius and his contemporaries present Nero as the devil incarnate, archaeological evidence paints a different picture. In the city of Pompeii, which was buried under volcanic ash only a decade after Nero’s death, remnants of graffiti indicate that he was surprisingly popular with the average Roman citizen. “Hooray for the decisions of the emperor and the empress,” one faded inscription reads, “with you two safe and sound, we are happy forever.”

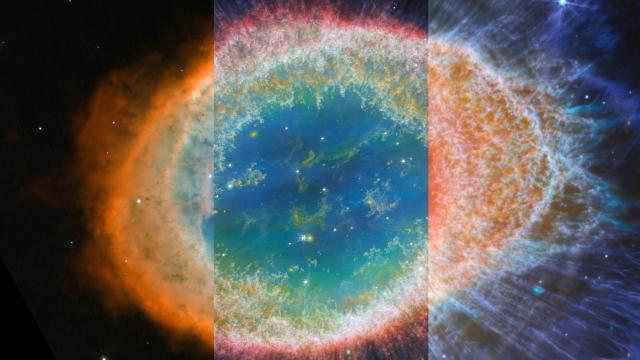

Archeological evidence might also clear Nero’s name with regard to his involvement in the Great Fire of Rome. The famous phrase “Nero fiddled while Rome burned,” should not be taken literally, even though it often is. Fiddles weren’t invented until the 10th century AD, and although Nero enjoyed playing the lyre — a similar instrument — no sources recall him doing so while the city was ablaze. Over time, “Nero fiddled” simply became shorthand for the idea that the emperor did not do enough to stop the disaster, as well as the rumor that he had been implicit in its ignition. The latter likely originated when, once the smoke had cleared, Nero announced plans to create his Domus Aurea or Golden House, a costly and spacious extension to his palatial complex the Roman elite – in the words of art historian Eric Varner – would have considered “very inappropriate.”

While Nero did indeed build his Golden House, whose ruins can still be visited today, this does not mean his attitude toward the fire and its victims was necessarily indifferent. This is the belief of Virginia Closs, a classics professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who in 2016 published a paper arguing that a group of neglected monuments scattered across Rome are in fact fire-safety measures installed by Nero circa 60 AD.

What an artist dies with me

If Nero’s infamy is to some extent a product of slander, it should be noted that his adversaries would have been driven by a variety of motivations, most of which were political. Despite enduring for hundreds of years, the Roman Empire was wildly unstable. Nearly half of all emperors wound up killed or deposed, their supporters purged and their legacies rewritten. As Livia Gershon points out in an article for Smithsonian Magazine, the writers that recorded Nero’s misdeeds “idealized the oligarchic Roman Republic,” whose demise was still fresh in their minds, “and disapproved populist rule by a single person.” Opper adds that Nero may have well-sought support from ordinary Romans to compensate for his unpopularity with the elite.

Aside from politics, this unpopularity appears to have been rooted in social norms as well. Nero may not have been a heathen like Julian – who sought to return paganism to the fully Christianized empire in which he grew up – or a crossdresser like Elagabalus — who, in addition to identifying with a non-Roman Sun god, playfully styled themselves empress — but Nero did have something else that alienated him from the establishment: his love of acting. In contrast to, say, the modern-day United States, where Ronald Reagan’s acting background helped rather than hurt his bid for the presidency, the Roman Empire looked down on entertainers, associating them with prostitutes.

Knowing this, it’s possible that Nero’s performances might have spawned the stories of sadism and sexual perversion we are familiar with at present. Going one step further, his equally familiar final words – “Oh, what an artist dies with me” – can be interpreted not as a demonstration of his incorrigible arrogance, but as his yearning for the profession society had denied him.

Of course, even if Nero didn’t “play the fiddle” while Rome burned or mass-massacre Christians – a religion Brent D. Shaw insists wasn’t yet large enough for its followers to have been slaughtered on the scale that the medieval Church believed they were – historians agree he likely murdered his mother and emptied the imperial treasury for his private parties, among other things. The point here, circling back to Opper, is not to “rehabilitate Nero as a blameless man,” but to show that Roman history and indeed ancient history as a whole is a highly contentious subject, that some people who are presented as heroes might in fact have been villains and vice versa.