5 harrowing paintings that capture the grim realities of war

- Where traditional painting glorified war, modern artists sought to expose its meaninglessness.

- Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí turned to abstraction to express the chaos and absurdity of conflict.

- Francisco Goya and Jan de Baen depicted scenes so disheartening that words cannot describe them.

In 1855, the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy published three short stories based on his experiences in the Crimean War, known collectively as the Sevastopol Sketches. Like many Russian noblemen, Tolstoy spent his adolescent years in the military and — like many — couldn’t wait to get his first taste of battle. Unfortunately, the reality of war was nothing like it had been described in myths, speeches, and history books. Expecting glory and valor, Tolstoy found only death and destruction. In his sketches, he reflects on the overwhelming stench of rotting corpses, the dull and lifeless look in the eyes of wounded soldiers, and the disorganized state of both the Russian and Ottoman armies.

Today, the Sevastopol Sketches are widely recognized as an early example of anti-war literature: a genre of stories that refutes traditional, more positive representations of war. Although rare before Tolstoy’s time, anti-war literature became more common after the First World War thanks to novels like Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front and Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms.

A similar pro-to-anti-war trajectory can be found in the realm of visual art. Famous paintings like Diego Velázquez’s The Surrender of Breda (1635), Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830), and Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851) are, in essence, illustrations of the viewpoint Tolstoy wanted to debunk. By crafting heroic displays of clashing militias and larger-than-life portraits of the generals leading them, artists throughout history helped to reinforce the notion that war is noble, justified, and synonymous with providence and progress.

But just as some writers started to accurately describe the horrors of war in their stories, so did painters begin experimenting with ways to depict them in visual art. Interestingly, where the former relied on realism, the latter turned toward abstraction. This is perhaps because the painter’s goal wasn’t to show what battles looked like — a task that had been relegated to photography as early as the American Civil War — but, rather, to communicate what fighting in one felt like.

Below are four famous paintings that were particularly successful in this endeavor.

Guernica by Pablo Picasso

The most famous and radical of the famous paintings on this list, Guernica is inspired by — and named after — the 1937 bombing of a town in the Basque Country in northern Spain. The bombing, which the Basque government says killed as many as 1,654 people, was carried out by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy at the request of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, who hoped to wipe out the Republican rebels located there.

Commissioned by the Spanish Republican government for the Paris International Exposition in 1937, Guernica is Picasso’s first work that makes a political as opposed to merely an aesthetic statement. Previously concerned with redefining what can and cannot be considered art, the artist uses abstraction to highlight the senselessness of this ideologically motivated attack. “The painting,” writes one critic, “does not render either a realistic or documentary account of the bombardment but rather alludes, by means of tonality, motifs, and both cubist and surreal stylistic devices, to the horrifying chaos made possible by modern technological warfare. [It] is symbolic, and the utterance has a universal, even cosmic, dimension.”

Joining the painting’s more recognizable figures — a woman falling from a house, a mother and child locked in embrace — are two of Picasso’s favorite symbols: the horse and the bull. If his earlier paintings depicting bullfights offer any guidance, the animals represent two sides of humanity: the horse being the feminine victim of the bull, and the bull, half removed from the scene and half part of it, being the male aggressor. Asked if the latter symbolized fascism, Picasso answered, in characteristically opaque terms, “brutality and darkness, yes, but not fascism.”

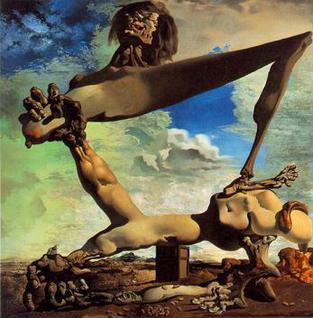

Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) by Salvador Dalí

Another painting of the Spanish Civil War, Dalí’s Soft Construction with Boiled Beans predates Guernica by a short year. Created before the conflict started, the always-eccentric surrealist claimed that the “prophetic power of his subconscious mind” had seen it coming. Although many art historians suspect Dalí changed the name of the painting retrospectively to enhance its appeal, it remains a striking image.

Like Picasso, Dalí used gendered symbols and bizarre imagery to express his attitude toward the conflict. The painting, in line with most of Dalí’s work, is as difficult to describe as it is to forget. A grinning, humanoid figure stands in front of what website dalipaintings.com describes as a “sunbaked” landscape. Precariously balanced and ripping itself apart, the figure — a mess of limbs without a torso to connect them — is an obvious allegory for the state of Spain. “The scattered beans of the title,” the website states, “exemplify the bizarre incongruities of scale to conjure the workings of an unconscious mind.”

Described by Dalí as a “delirium of autostrangulation,” Soft Construction with Boiled Beans takes less of a metaphorical and more of a psychoanalytical approach to the Spanish Civil War. Psychoanalysis and surrealism — the genre of painting to which Dalí subscribed and which he now epitomizes — go together like Tolstoy and Russia. Both the psychoanalyst and the surrealist seek to understand the waking world through the seemingly absurd but actually quite sensible construction of dreams. In the painting, Dalí pays homage to Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, with a small portrait hidden in the corner of the frame. More obvious are the many breasts and penises emerging from the possibly climaxing figure. Comparable in meaning to the bull and horse in Guernica, they suggest that the Spanish Civil War was an act of sexual perversion.

The Third of May 1808 by Francisco Goya

Yet another painting from Spain, this time from a different historical period. The Third of May 1808 — considered, with the possible exception of his infamous “black paintings,” to be Goya’s masterpiece — depicts the aftermath of a failed uprising against the French occupation of Spain, which began a year earlier when Napoleon Bonaparte replaced King Charles IV with the former’s own brother, Joseph.

On May 2, 1808, street fights erupted in Madrid after French soldiers opened fire on crowds protesting in front of the city’s royal palace. Hundreds of protestors were arrested and placed in front of a firing squad the following day. Goya’s striking composition reveals his thoughts on the event: The French executioners, their backs turned towards the viewer, are almost machinelike in their conduct. Our focus (and sympathy) is aimed at the poor rebels, one of whom spreads his arms to imitate Christ on the cross.

This unambiguous picture serves as an entry into Goya’s surprisingly complex worldview. Although understanding of the rebels, the painter had long criticized Spanish society under the rule of Charles IV and his despotic son Ferdinand VII. At the same time, he was harboring a not-so-secret love for “enlightened” rulers like Napoleon. The Third of May 1808 was painted more than six years after the executions took place and was commissioned by Ferdinand, presumably to challenge Goya about his allegiances during the occupation. Consequently, the painting’s most striking feature — the moral contrast between the righteous Spaniards and the heartless Frenchman — may actually be the result of the painter trying to escape persecution, rather than expressing his unfiltered feelings.

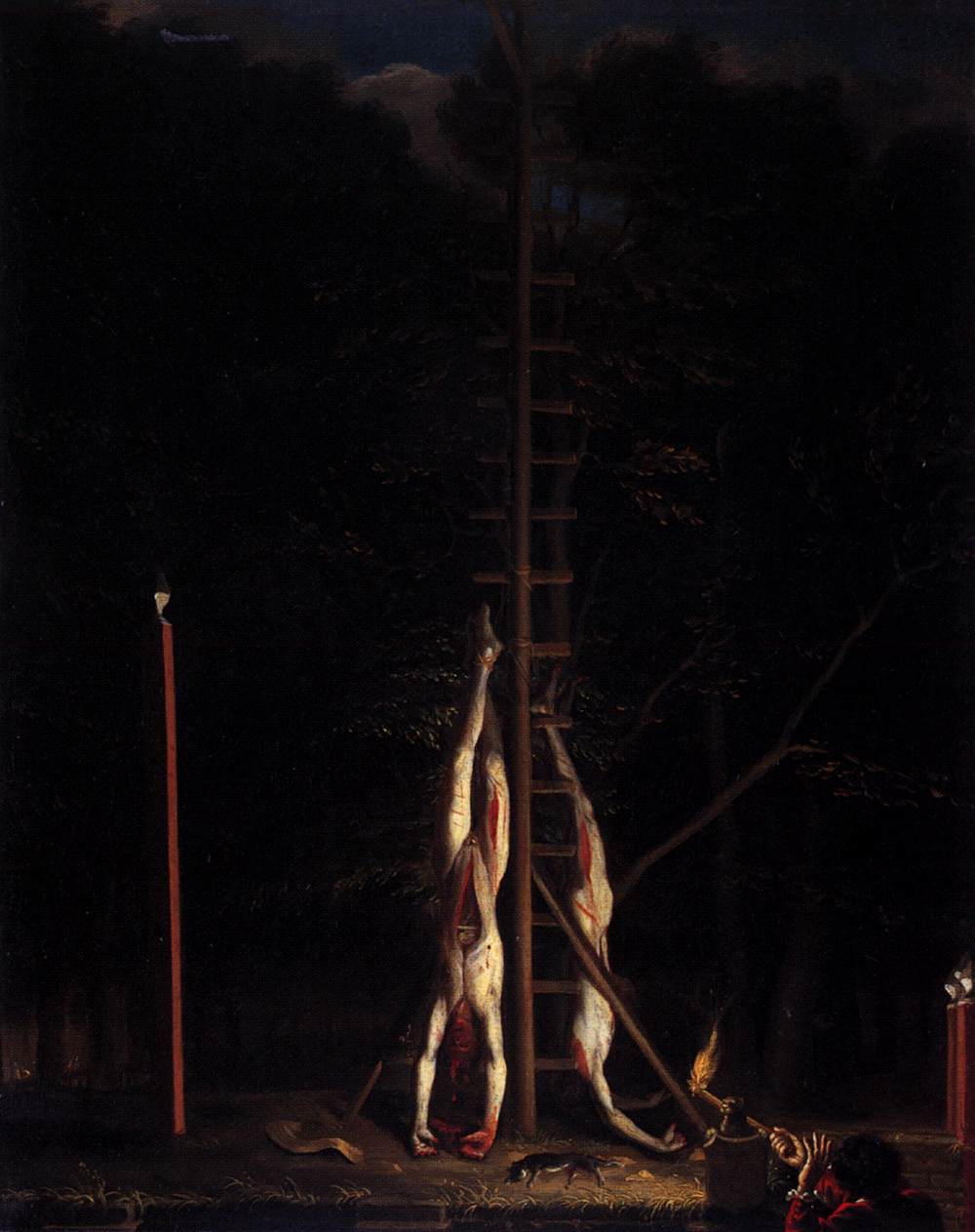

The Corpses of the Brothers De Witt by Jan de Baen

In Dutch history, 1672 is known as the Rampjaar, or “Disaster Year.” This is because, in April, the Republic of the Netherlands went to war with — and was ultimately defeated by — a joint alliance involving England, France, and the bishoprics of Munster and Cologne. With the end of the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age in sight, citizens of the Hague unloaded their anger on the Republic’s Grand Pensionary, Johan De Witt, who along with his brother Cornelis was brutally lynched not far from his own office.

A 1672–1675 painting attributed to Dutch artist Jan de Baen shows what was left of the brothers after the mob had dispersed: They were stripped naked, strung from a wooden post (Johan slightly higher than the older but less powerful Cornelis), castrated, and disemboweled. Faithfully following eyewitness accounts, De Baen painted the brothers without fingers or toes (these were cut off and sold as souvenirs) and even added the remains of a cat one rioter was said to have stuffed inside Cornelis’ body.

Occasionally compared to studies of butchered animals like Rembrandt van Rijn’s 1655 Slaughtered Ox, The Corpses of the Brothers De Witt is perhaps more akin to a form of historical documentation. Like some of the early etchings it was based on, it has appeared in texts old and new to illustrate something so gruesome words cannot describe. Art historian Frans Grijzenhout, writing in the Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, went as far as to argue the painting “could be interpreted as some kind of inverse political double portrait,” a commemoration of the De Witts’ career and the terrible fate awaiting them at its end.