Wharton School of Business professor Adam Grant believes it’s time to stop focusing on “natural talent.” He shares his experience growing up not feeling good at doing anything in particular and how he overcame that to achieve his highest potential.

He also shares a key phrase for inspiring others as leaders and maximizing their performance.

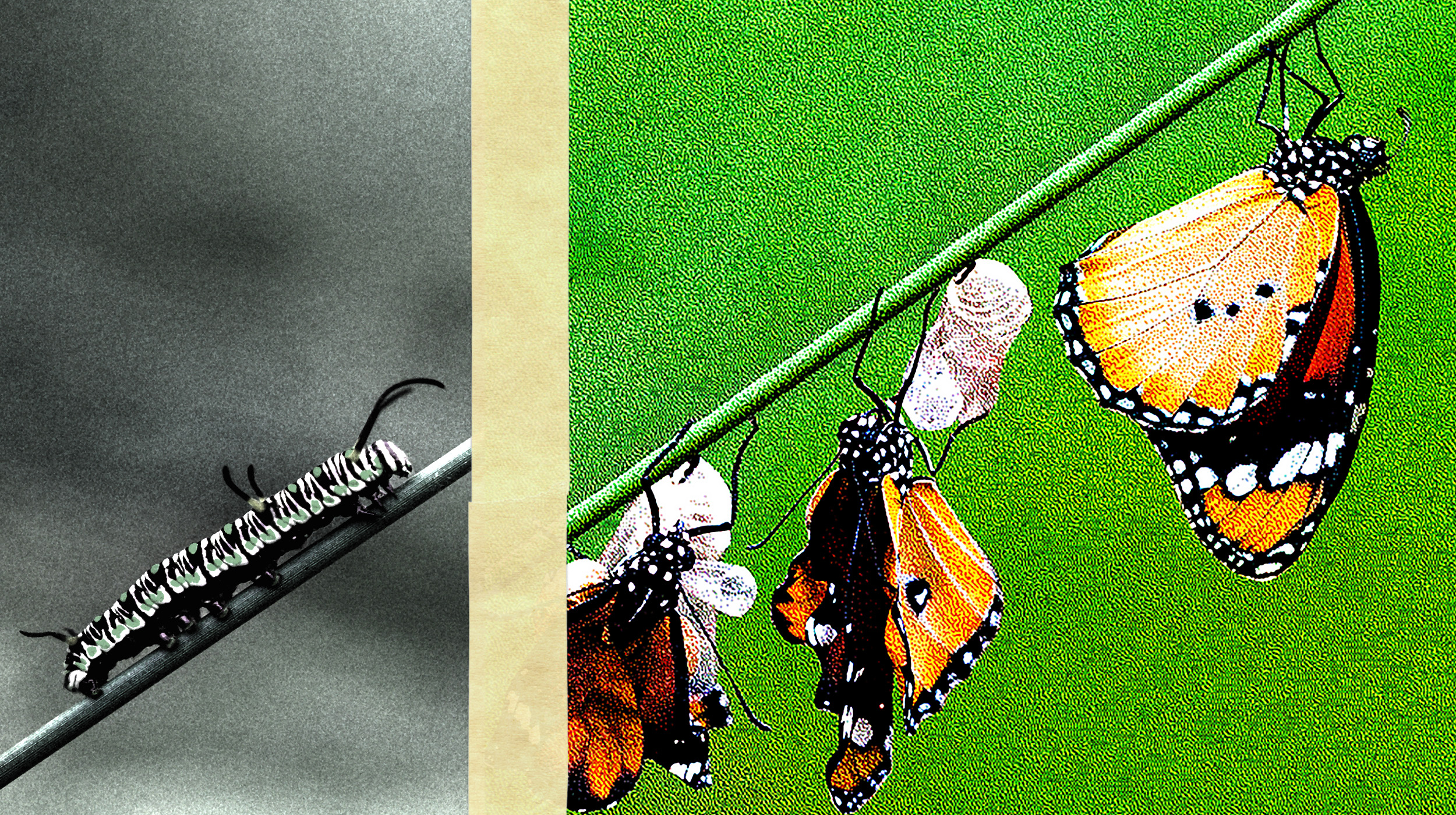

ADAM GRANT: We live in a world that's obsessed with raw talent. We admire child prodigies in music, natural athletes in sports, geniuses in school, but focusing on where people start causes us to overlook the distance that they're capable of traveling.

I'm Adam Grant. I'm an organizational psychologist at Wharton and the author of, "Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things." I got interested in this topic personally because I started out as a springboard diver with zero talent. I was told that I walked like Frankenstein, that my coach's grandmother could jump higher than me. I couldn't even touch my toes without bending my knees. Clearly the wrong sport for me. If I had judged my potential by that starting ability, I would've quit.

With an extraordinary coach and a lot of effort, I ended up becoming a Junior Olympic national qualifier and an All-American diver. I ended up actually exceeding what I thought was my potential. That happened to me again when I started out trying to teach as a professor. The comments from students were brutal. I remember one student writing that I was so nervous I was causing them to physically shake in their seats. Another student wrote that I reminded them of a Muppet, and didn't even tell me which Muppet.

But we should be looking for the answer.

I was not an effective teacher. I was too anxious. But once again, I had some coaches who really believed in me and I put a lot of effort into studying my teaching, into watching great teachers, and trying to figure out how I could become a little bit more effective in the classroom, and I made radical changes. Lo and behold, the feedback was night and day different.

I care deeply about this topic of potential because we all have more capability for growth than we realize, and if we focus just on early talent and on initial performance, we're going to miss out on the progress that we're capable of achieving. One of my greatest disappointments in life has been seeing people squander their potential. We constantly underestimate our own capacities, and we're also vulnerable to underestimating what other people are capable of achieving.

The measure of a leader's success is how much the groups they're in charge of ultimately accomplish. That means that if you fail to help people realize their potential, you are failing as a leader. When I work with leaders, I tend to see them fall into one of two traps when it comes to developing their people. One is that they're cheerleaders and the other is that they're critics.

If you're a cheerleader, you recognize people's best selves and you try to harness their strengths, but there's good empirical evidence to suggest that when we become too comfortable with our strengths, we start to use them as a crutch. And they can even become career derailers. So if one of your strengths, for example, is charisma, you are at risk for under-preparing when it comes to leading a meeting or giving a speech because you're so good at improvising and speaking extemporaneously, you may not do your homework.

I don't think you just want to be a cheerleader because you are in danger of letting people turn their own strengths into weaknesses. I think the problem with critics is they often deflate the people around them. If you're constantly telling people what they're doing wrong, people get discouraged really quickly. Their motivation starts to falter. At some point, they begin to doubt whether they have any potential at all.

I think the best leaders are neither cheerleaders nor critics. They're actually coaches. They see people's potential and they try to help them become a better version of themselves. They allow people to recognize their strengths but not get complacent around them. They allow people to see their weaknesses but not get discouraged by them. And they remind people, "Yes, you might be pretty good today, but you're capable of becoming even greater tomorrow." And that energizes people to want to become better as opposed to being comfortable with where they are or completely incapable of growing from where they're stuck.

To help people realize their potential, every coach needs to be comfortable delivering feedback. A lot of leaders end up waiting till performance reviews to deliver the unvarnished truth. That comes as a surprise then to their direct reports, who, for the last six months, thought everything was fine. If you deliver a message during a performance review that comes as a surprise to anybody on your team, you have failed at leadership. You have failed to give the feedback in real time so that they can learn from it, adapt, and make an effort at improving. The longer you wait, the harder it gets to encourage people to change and the less likely they are to even believe your message in the first place.

As a leader, I want to build the person up as opposed to tearing them down. A lot of us instinctively try to do that by serving up the feedback sandwich. Let me take a compliment, a piece of criticism, and then another compliment and that way I can sandwich my critique between two slices of praise. Well, guess what? Empirically, the feedback sandwich does not taste as good as it looks. If the person you're serving it to is anxious at all, they're not even going to hear the praise. They're just waiting for the other shoe to drop. If they're pretty confident, they're going to fall victim to primacy effects and recency effects. So they're going to remember the first compliment and the last compliment, and what happened in the middle is just going to get erased from their memory.

What's much more effective is to start off by clearly segmenting your domains of praise from your domains of constructive criticism. So I would go into this conversation and say, "I want to tell you a couple of things you're doing well and a couple of things that you could work on improving. Do you have a preference for which we do first?" I'm not only clearly segmenting the praise from the criticism so that they can realize those are separate things. I'm also then making this a two-way conversation as opposed to a one-way monologue.

One of the biggest mistakes that leaders make when they give feedback is they spend too much time judging the person and not enough time trying to focus on behavior change. When you start to tell people what they do wrong consistently, what makes them ineffective or incompetent, you invite their ego to show up. Nothing is going to get through. If you can tell people one or two things that they could do better, instead of trying to prove themselves, they're much more open to figuring out how they can improve themselves.

A study published on this a few years back showed that you can make people significantly more open to constructive criticism just by saying about 19 words before you deliver it: "I'm giving you these comments because I have very high expectations and I'm confident you can reach them," and you should do that in your own words. That completely changes the tone of the conversation. "I'm not attacking you, I'm not judging you. I'm here to coach you and help you grow." It turns out it is surprisingly easy to hear a hard truth from someone who wants to help you succeed. And if I want to reinforce that further and take myself off the pedestal, I'll conclude by saying, "Is there anything I can do better? Is there something you want me to know about how I can work more effectively with

you?" And that way we're building a foundation for a better collaboration as opposed to me just telling you what you need to change.

Just like in a marriage, that would probably not work very well if you tell your spouse, "It's not me, it's you." As a leader or manager, the same principle applies. If you show a willingness to grow, the other person is a lot more excited about trying to grow with you.

NARRATOR: Get smarter faster with videos from the world's biggest thinkers. To learn even more from the world's biggest thinkers, get Big Think Plus for your business.