The Rocky Horror Picture Show has surprising roots in Victorian seances

“Worms will crawl over your face! Ghosts will roam the aisles!” Dr. Silkini warns as the Frankenstein monster slowly comes to life onstage, “If the lights go out, stay in your seats!” Suddenly possessed by a fit of rage, the monster strangles the hunchbacked assistant and charges into the audience with a roar. As the front row squeals in anticipation, there is a blinding flash, and the lights suddenly go off.

Pandemonium erupts in the pitch black theater. There are screams, macabre laughter, wild howling. Glowing skulls appear and disappear. Something slimy slaps your head and slithers over your face. You furiously bat away what indeed feels like worms. A strange luminous form floats overhead. On the stage, a kick-line of skeletons dance and then fly apart. The little boy next to you turns, and his face glows in the dark.

A moment later, the logo for Universal Pictures flickers to life on the movie screen. Everyone giggles with relief as they settle back to watch a cheesy horror film.

A campy interactive horror show with a mad scientist? No, this isn’t The Rocky Horror Picture Show—though it is related. This is Dr. Silkini’s Asylum of Horrors, one of the many midnight spook shows that were ubiquitous in America from the 1930s to the 1960s.

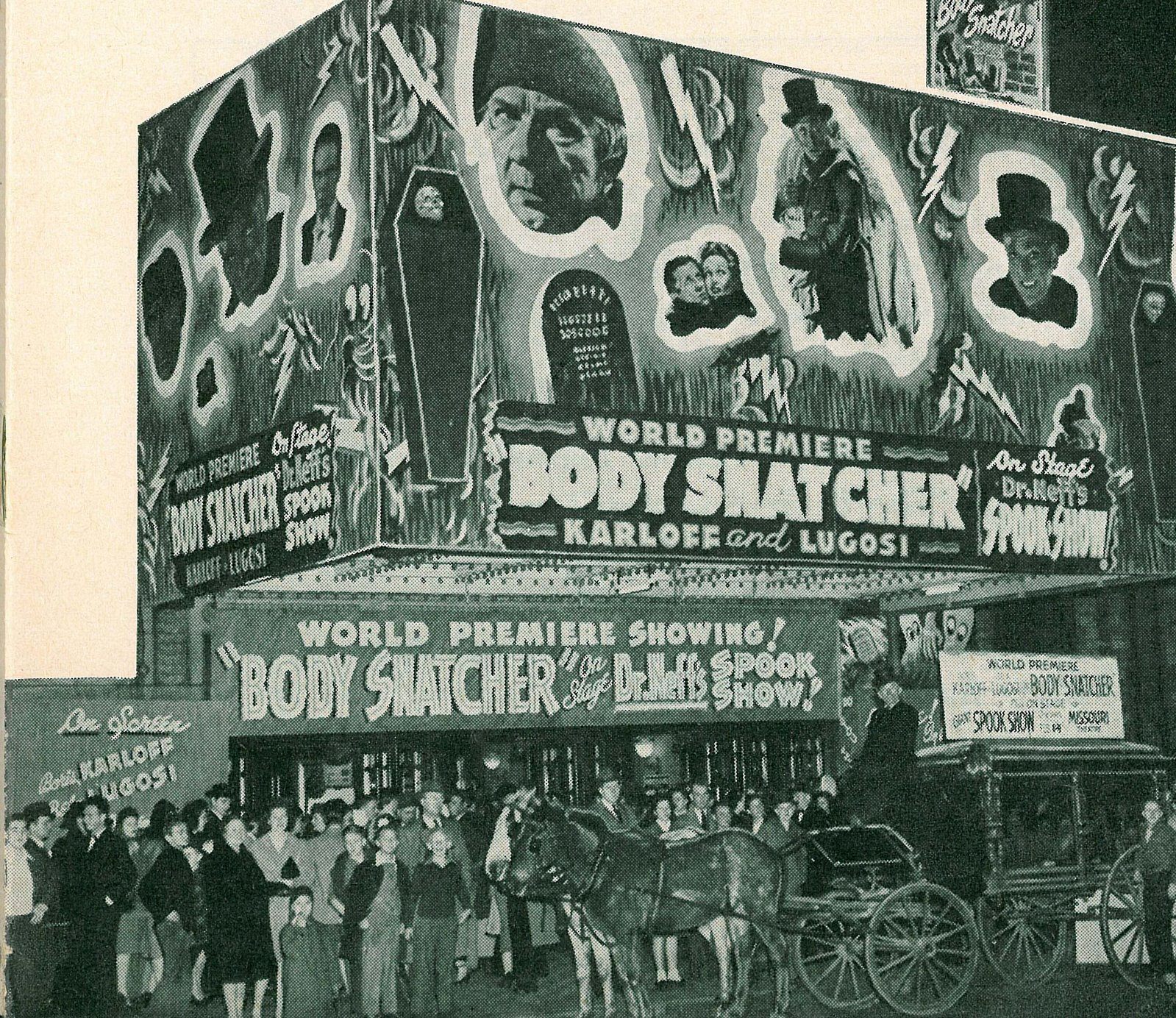

Now all but forgotten, spook shows were a “winning trifecta of spooky-themed magic shows, ghost blackout segments, and fright films, presented in lavish motion picture houses,” according to Mark Harris, author of Ghostmasters, the definitive study on spook shows. The interactive performances were shown in movie theaters usually at midnight.

Though they were popular in the mid-1900s, spook shows—and Rocky Horror itself—have roots in 1800s séances. A steady, spooky line throughout history shows how Victorian séances were incorporated into magic shows, which were then taken to the movie theaters as spook shows, where live performances were paired with horror films, which led to the audience-interactive Rocky Horror Picture Show. It’s a long, rewarding journey through time, with many spirits and monsters along the way.

If you enjoy jumping out of your seat to dance the Time Warp, you can thank Maggie and Kate Fox. In 1848, the Fox sisters convinced their neighbors that they were in contact with a spirit who was making strange knocking sounds. Within a few years, they had sparked a cult movement. Thousands of people flocked to séances where mediums manifested progressively flashy phenomena that purported to indicate the presence of the dead. Tables turned, furniture floated in the air, and mysterious messages appeared on slates.

Magicians at the time had mixed reactions to the popularity of séances. Harry Houdini famously led a crusade against psychic mediums, announcing in the Los Angeles Times, “It takes a flim-flammer to catch a flim-flammer.” Other magicians, among them Thurston and Harry Kellar, began to incorporate ghostly elements into their conjuring repertoire. “By 1896, there was hardly an illusionist in Europe or America who was not including at least one spiritualistic séance as part of his act,” notes historian Mervyn Heard in Phantasmagoria: The Secret Life of the Magic Lantern.

One magician named Elwin-Charles Peck was the first to bring the performance to movie theaters. In 1929, Peck (whose stage moniker was El-Wyn) approached a theater and asked if he could put on a magic show after the last screening. Vaudeville was on the wane by then, and there were fewer venues in which magicians could perform. Meanwhile, movies were rising to dominate popular entertainment. Peck’s idea to pair a spooky magic show with a supernatural picture show at midnight was a stroke of entrepreneurial genius. He became the first spook-show operator or ghostmaster.

Calling his production “El-Wyn’s Midnite Spook Party”, Peck took spiritualism in a devilish new direction. Yes, messages appeared on slates and tables floated in the air, but Peck did away with the dramatic sob fest connecting a grief-stricken mourner with their dearly departed (the part that most invited scrutiny). Instead, El-Wyn’s Midnite Spook Party played the séance for cheap thrills and jump scares. Peck’s coup de grâce was a climactic blackout in which he pelted the audience with three minutes of supernatural effects in the dark.

El-Wyn’s Midnite Spook Party was a smash hit, and he was soon selling out midnight shows throughout the country. Other magicians began presenting their own spooky magic shows in tandem with midnight movies. They also copied Peck’s blackout finale, complete with glowing skulls and flying cheesecloth dipped in luminous paint. When the ghostmasters mentioned falling spiders and worms, assistants dropped popcorn on audiences and dangled damp mop strings on people’s faces. A new theatrical form was born, made out of huckster showmanship and the band-new wonders of glow-in-the-dark paint. By the mid-1930s, numerous spook shows were touring the United States, proliferating in concurrence with the rise of horror films.

The spectacular success of Dracula and Frankenstein in 1931 established Universal Pictures as the foremost producer of horror films and officially launched the horror genre. Other studios began cranking out gothic films to cash in on the fad. The accompanying spook shows were as goth as the films they preceded, with ghostmasters presenting supernatural illusions in Victorian drawing room settings. As the horror genre became more sci-fi in the 1940s, ghostmasters morphed into mad doctors in lightning-filled labs and the spook show became a monster show.

Ghostmasters continued to develop creative stunts throughout the 1950s. Kara Kum’s outrageously gory shows featured decapitation, cannibalism, and the materialization of James Dean. Asylum of Horrorsby Dr. Silkini was more like a horror-themed carnival sideshow featuring Frankenstein’s monster. At the other end of the spectrum was the consummate Madhouse of Mystery, renowned for its astonishing blackout sequence, after which illusionist Bill Neff would wish the audience “pleasant nightmares.” Other successful spookers include Zombie Jamboree by Ray-Mond, notorious for a bloody scene in which a team of mad doctors operate on a hapless volunteer from the audience.

Spook shows also capitalized on Hollywood fandom. Glenn Strange, who played Frankenstein’s monster in three Universal films, toured as the monster in Don Brando’s Tomb of Terror in 1947. Bela Lugosi, who rocketed to fame as Dracula, donned his cape and fangs in Bill Neff’s midnight show. Lugosi later helmed his own spook shows when movie roles dried up.

The popularity of spook shows started to wane with the rise of television. People began staying home for their entertainment, especially after TV started offering midnight programs that mimicked spook shows. The first of these was The Vampira Show in 1954. While there is no way to drop spiders through a TV screen, Vampira roughly followed the spook show format by amusing her audience with eerie antics before introducing a campy horror film. In 1957, Screen Gems began showing classic horror films in a late-night television show called Shock Theater. Again emulating spook shows, the program was hosted by ghouls, mad doctors, and Eastern European nobility.

Still, spook shows did continue in movie theaters, though they were beginning to look a little passé paired with the darker horror films of the 1960s. In response, spook shows amped up the sex and violence. Scantily-clad ghostesses paraded their hex appeal onstage. Assistants were brutally decapitated. Though audiences were shrinking, the zero-budget spoof Monsters Crash the Pajama Party was specifically produced in 1965 to be used in a spook show. Part way through the movie, a gorilla crashes out of the frame as the film goes black. At the same time, a spook show assistant in a gorilla suit is meant to pop out and kidnap an actress planted in the audience wearing a white dress. When the film resumes, a woman in the same dress is dragged into the lab to be tortured.

By the 1970s, horror had become too serious, bloody, and dark for spook shows. Jump scares just didn’t fit with The Exorcist and Carrie. By then, magicians had also found it too cost prohibitive to mount a proper blackout sequence. But while the spook show disappeared, the precedent for midnight movie screenings remained—and headed underground. “A distinctive strain of subterranean moviegoing had developed, after hours and under wraps,” wrote J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum in Midnight Movies.

The counterculture scene from the 1960s through the ‘70s came with an explosion of underground films, played at clubs and niche cinemas. Midnight was reserved for the most outlandish films. In New York, the Elgin Theater became known for turning subversive films into cult hits through midnight screenings, starting with Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo in 1970 and continuing with John Water’s Pink Flamingos and The Harder They Come starring Jimmy Cliff.

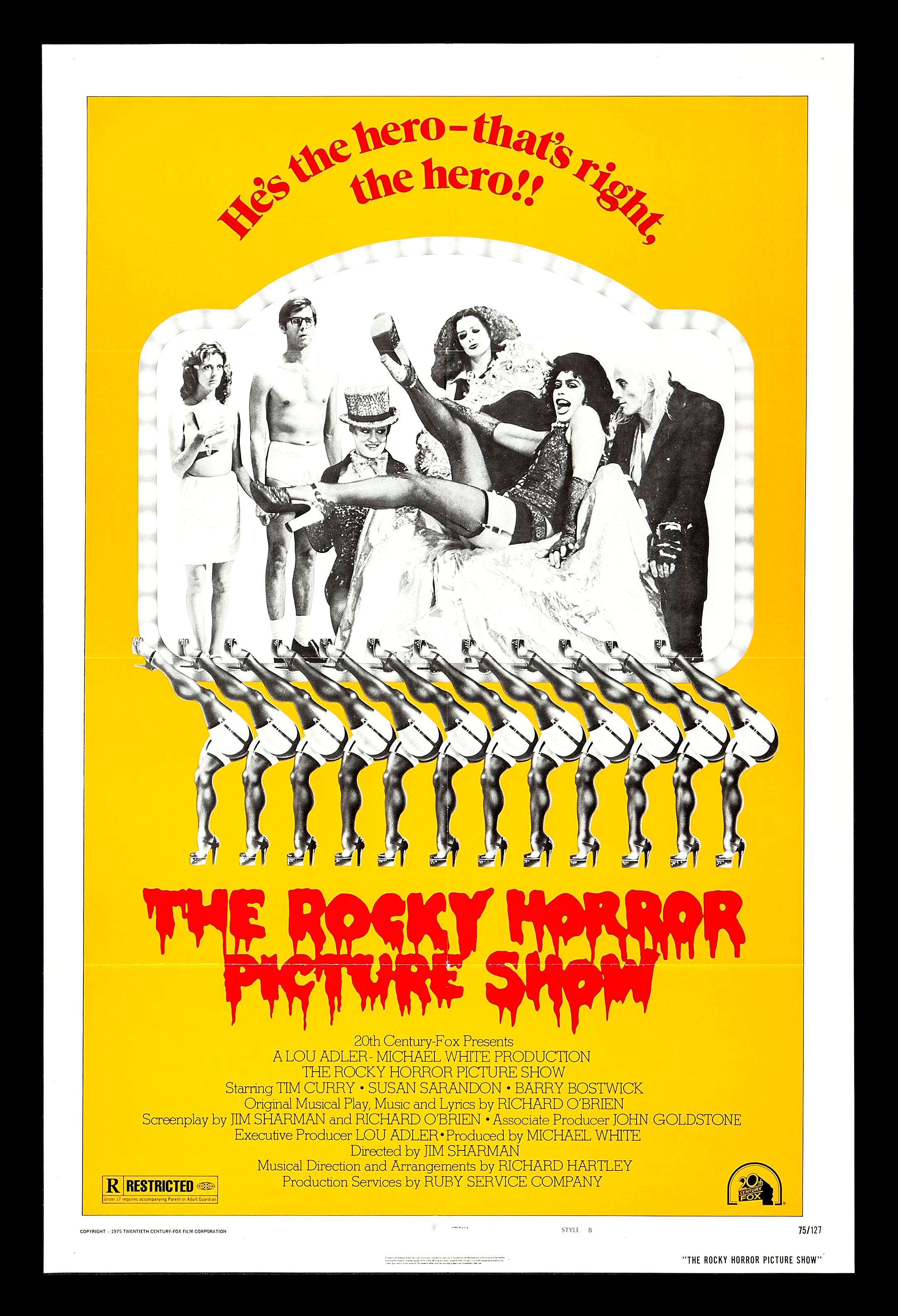

And then The Rocky Horror Picture Show came along. With campy horror a relic of the 1950s, no one anticipated just how big the film would become. Rocky Horror started out as a musical play performed at the Royal Court Theatre in London in 1973. It was hugely successful and went on to more theaters before being adapted into a movie. But when the film was released in a few test market cities in 1975, reviews were dismal and the national release was canceled.

Everyone was ready to shelve the film except for Tim Deegan, the 26-year-old publicist assigned to the film by 20th Century Fox. Hoping to emulate the success of Pink Flamingos, he secured a midnight run at the Waverly Theater in New York City in 1976. Within a few weeks, a group of rowdy fans—emboldened by the gay rights movements of the time—began regularly attending and interacting with the film, which celebrates both a self-proclaimed “transvestite from Transylvania” and every schlocky horror trope.

The cult classic took off. Audiences began flocking to movie theaters at midnight to interact with performers dressed up as characters from the film while the movie played on the big screen. This time, rather than following instructions from a ghostmaster or magician, audiences came up with their own thrills, throwing toast and rice on cue or squirting water guns during certain scenes.

Today, Rocky Horror is the longest running film in history, playing at a movie theater somewhere in the world every night for nearly fifty years, often accompanied by live performers, costumes, choreographed dance moves, and stunts. Little do many fans know that in addition to paying homage to the science fiction double bills of yesteryear, they are also channeling the raucous spirit of midnight spook shows. With a mad scientist, gory death scenes, cannibalism, and rowdy audience interaction, it seems all that’s missing is the blackout and luminous paint—and maybe some floating furniture.

This article originally appeared on Atlas Obscura, the definitive guide to the world’s hidden wonder. Sign up for Atlas Obscura’s newsletter.