Will 2023’s Geminids be the best of all-time?

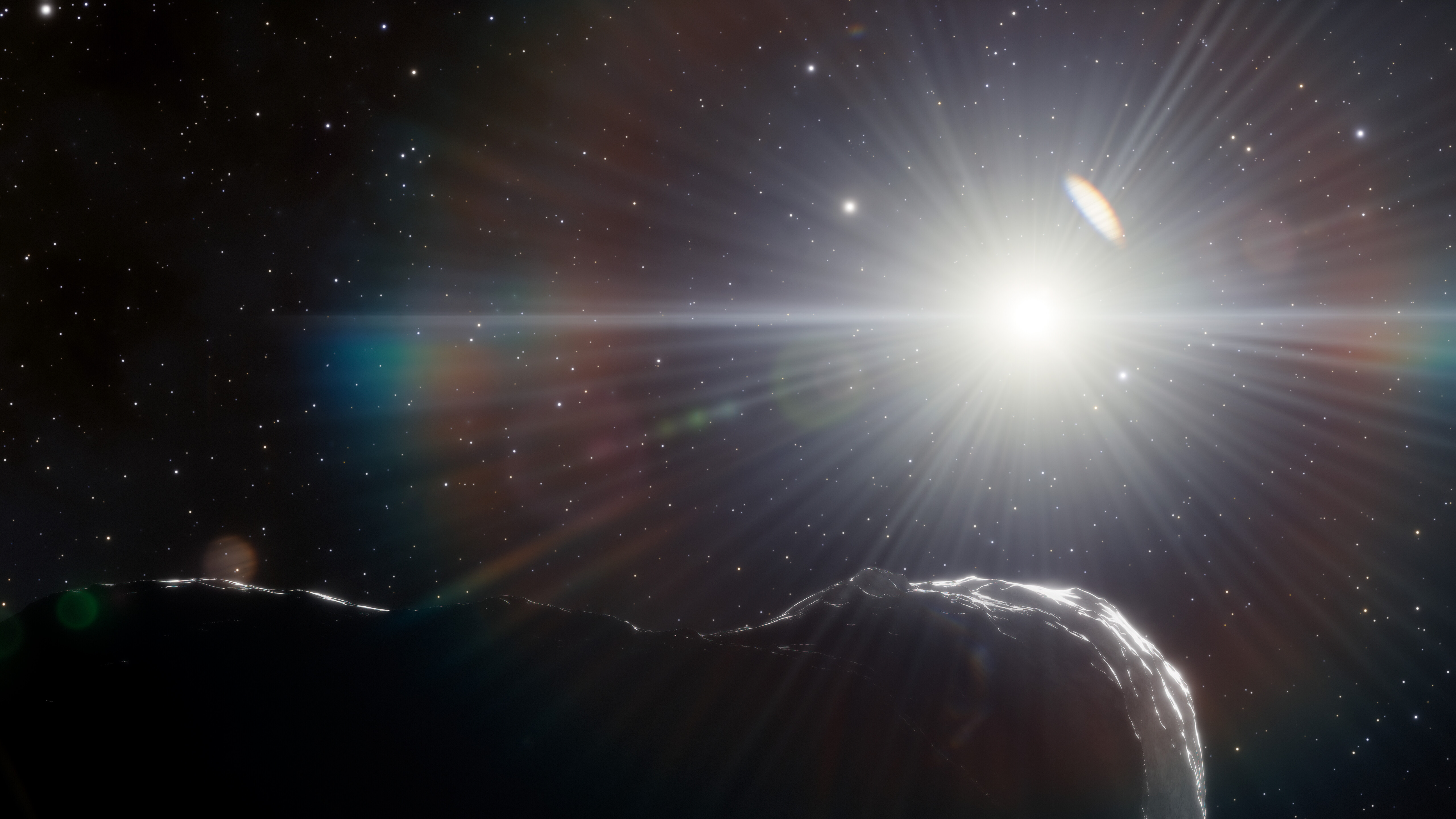

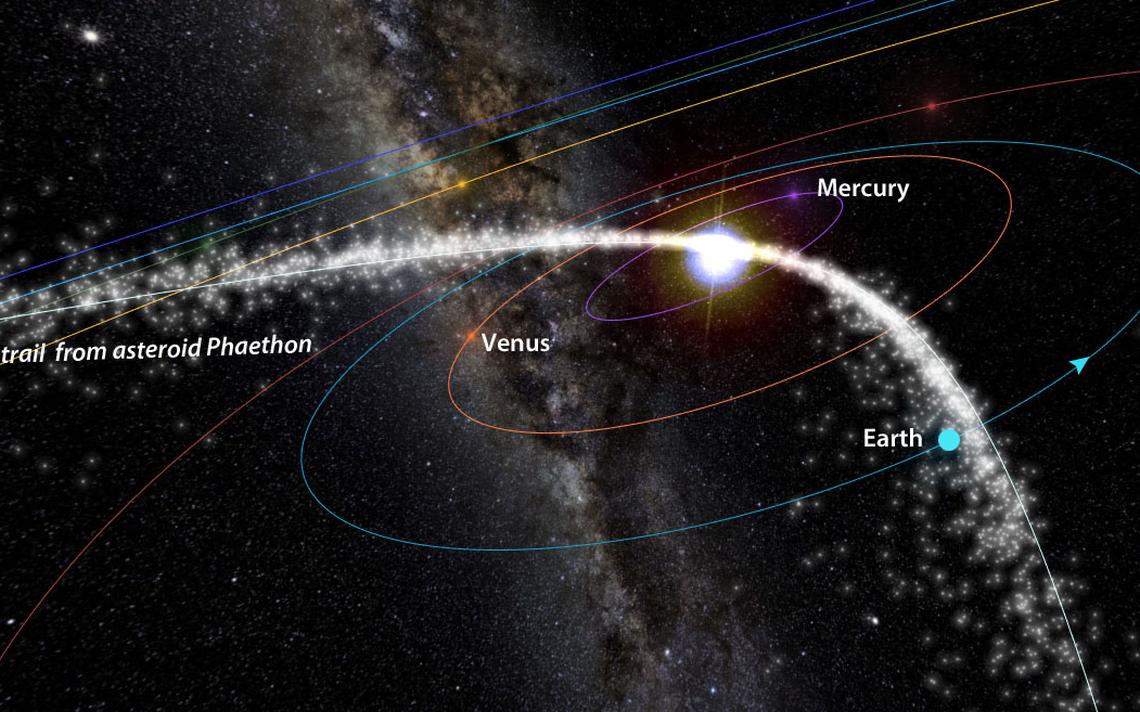

- While most meteor showers are generated by the debris streams of comets that cross Earth’s orbit, the Geminids are generated by a slowly disintegrating asteroid: 3200 Phaethon.

- As the years go by and the asteroid continues to disintegrate in the Sun, its debris stream becomes thicker and denser, leading to greater numbers of meteors when Earth passes through that stream each December.

- The peak of 2023’s Geminids, overnight from December 13-14, comes just one night after the new Moon, creating a low light pollution environment for a spectacular show. Could it be the best one ever?

Every year, no matter what else is occurring on Earth or in the heavens, you can rely on two meteor showers putting on a show: August’s Perseids and December’s Geminids. When the Moon isn’t out and sky conditions are favorable, the peaks of both of these meteor showers can lead to skywatchers all over the world seeing a hundred or more meteors every hour, making them two of the most reliable night sky events that recur annually. The reason is simple and straightforward: as volatile-rich bodies travel through the Solar System, they outgas and fragment when they get too close to the Sun, and the parent bodies of both the Perseids and Geminids have been stretched out into dense debris streams that, when Earth plows through them, create a spectacular, meteoric show.

But this year, in 2023, a series of events are all aligning, simultaneously, that could make this the best Geminid meteor shower of all-time. The shower itself is strengthening on an annual basis, as the debris stream that creates the Geminids thickens with each orbit of its parent body: Asteroid 3200 Phaethon. The Geminids occur very close to Earth’s perihelion: when our orbital speed is greatest, leading to faster meteors. And this year, the December 13/14 peak of the Geminids coincides almost perfectly with a new Moon (which occurs on December 12), creating near-perfect sky conditions. Here’s how to make the most of the experience.

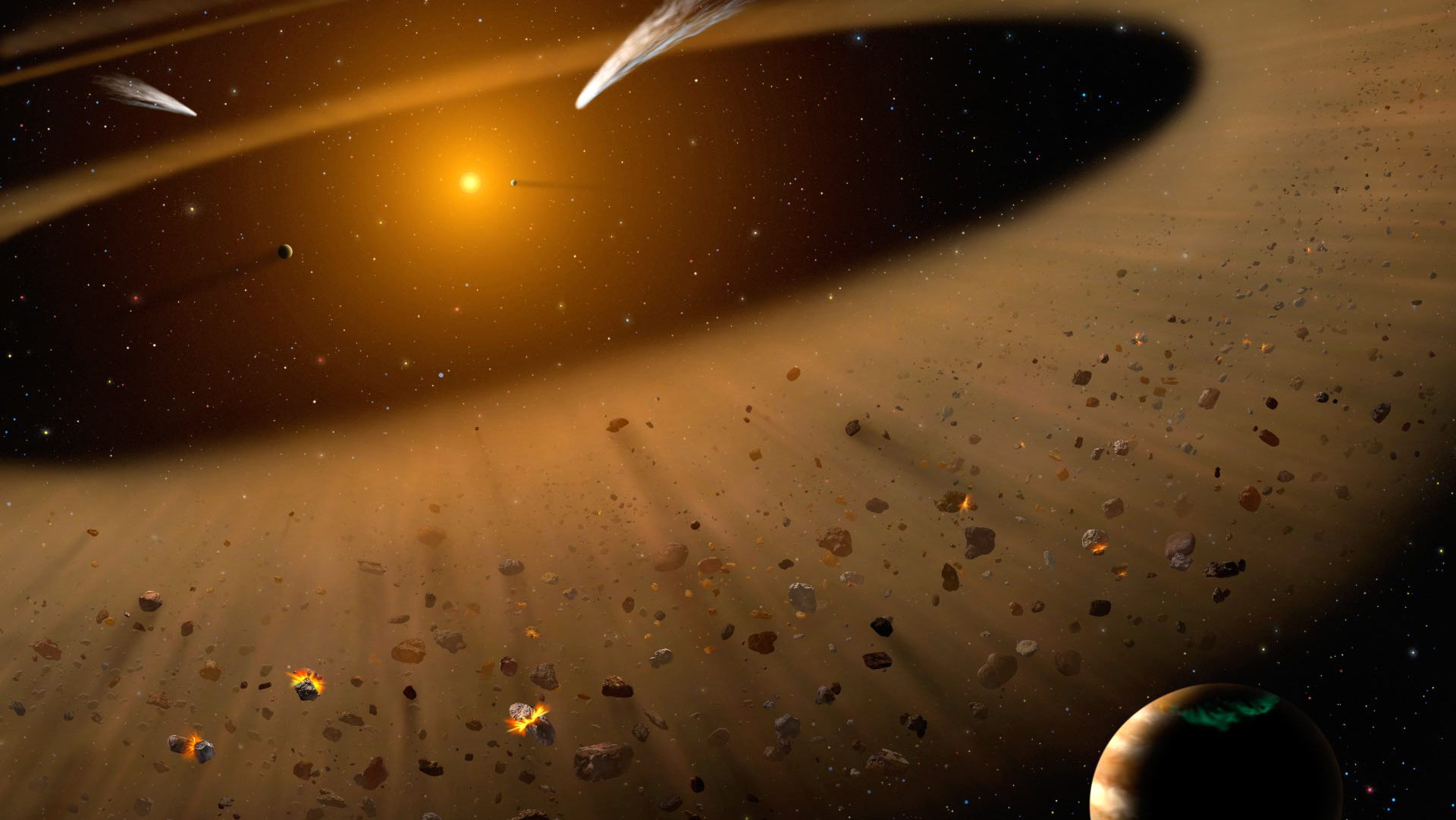

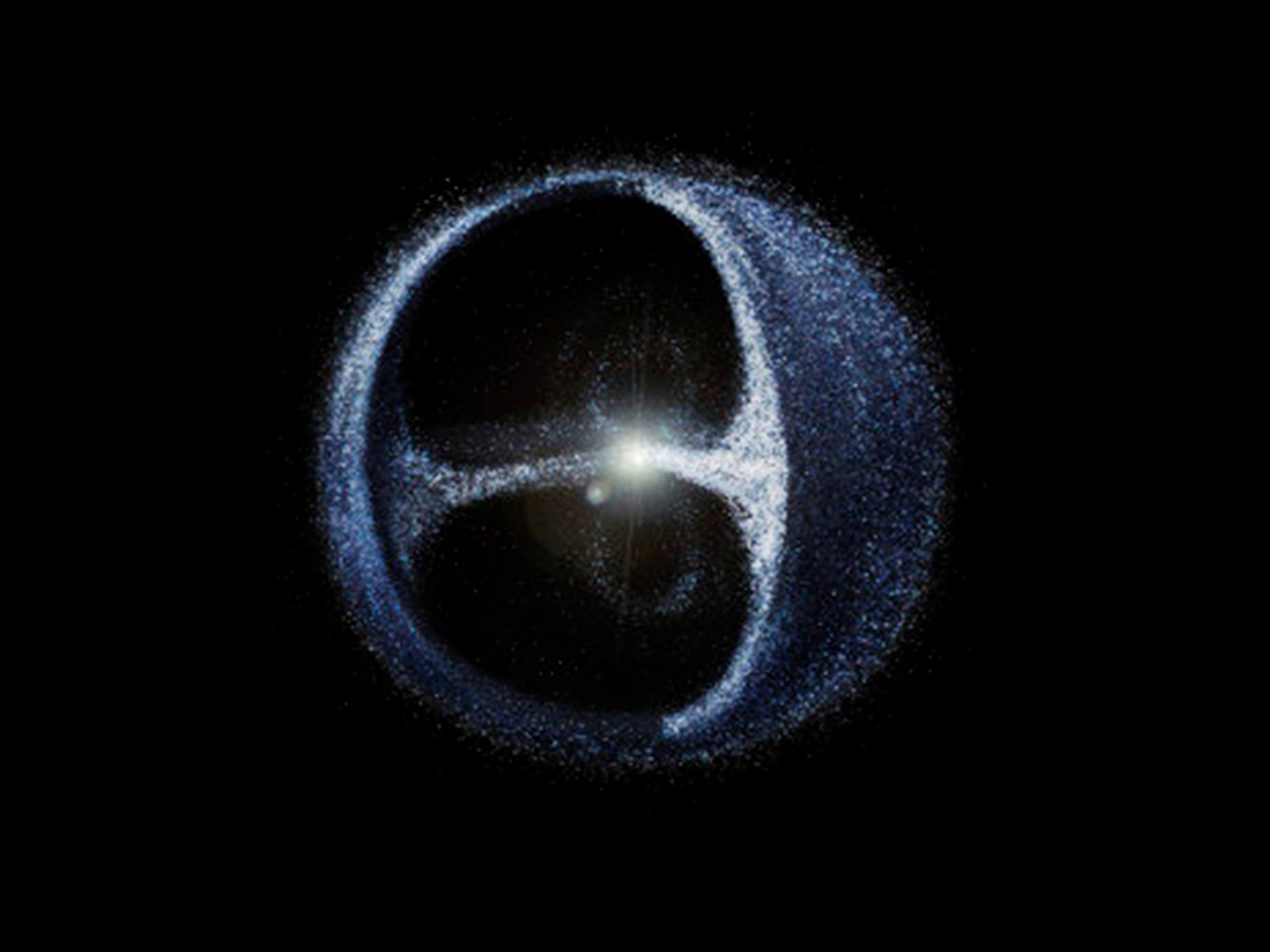

In all known cases, meteor showers arise from a parent body, like a comet or asteroid that’s passed close to the Sun and has heated up to the point where it’s produced tiny particles from a combination of off-gassing, tidal forces tearing it apart, and solar wind and radiation striking these loosely-held surface particles. These tiny particles are known as a debris stream, and they get stretched out across the comet’s (or asteroid’s) orbit. Whenever planet Earth itself plows through that debris stream, these particles strike Earth at a tremendous speed — dozens or even close to a hundred km/s — creating the spectacular display known as a meteor shower.

Because Earth itself orbits the Sun in a predictable fashion, it always strikes the same debris stream at the same angle and speed on a year-to-year basis. Moreover, since the Earth moves in the same direction with a one-year period, the meteors associated with a meteor shower always appear to originate from the same location in the sky: known as the radiant of the meteor shower. Meteor showers themselves bear the name of the constellation in which the radiant (or “point of origin”) appears, with the Geminids being named for the constellation of Gemini: “the twins” in Greek Mythology.

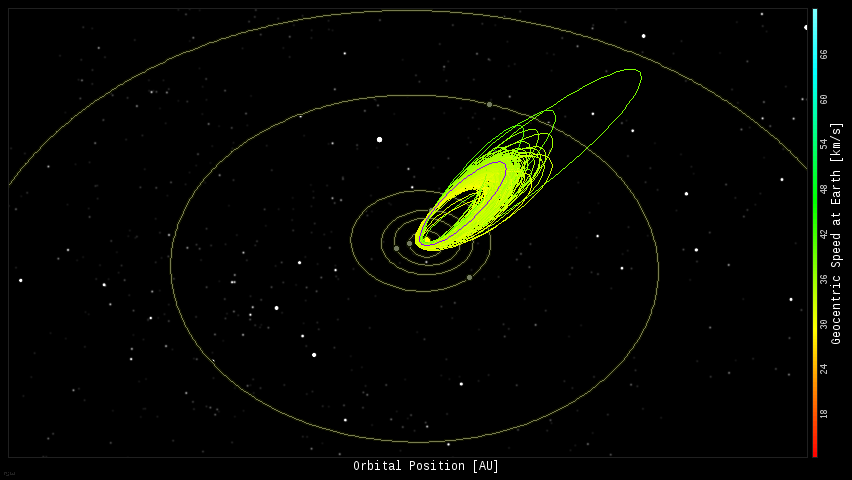

The two “twin” stars are named Castor and Pollux, with orange Pollux being the 17th brightest star in the sky and blue Castor coming in at the 24th brightest. These stars rise around sunset from the Northern Hemisphere and around midnight in the Southern Hemisphere, while the Geminid meteors themselves all streak away from that point. They typically strike Earth at about 35 km/s, creating multicolored streaks when they burn up in Earth’s stratosphere, with the yellow-white colors being the most common among the meteors you’re likely to see.

The Geminids are a little unusual for a meteor shower. Whereas many of them go back in history a thousand years or more, the Geminids were only first spotted in 1862. Initially, they were a modest meteor shower, with relatively small numbers of somewhat faint meteors. Over the century-and-a-half since they were first spotted, the Geminids have remained on the faint side — typically about +2 astronomical magnitudes fainter than the brighter Perseids which appear in August — but have become the most reliably productive meteor shower in our skies.

To watch the Geminid meteor shower, all you need is:

- a clear, dark sky,

- some warm clothing to make the December night bearable,

- and knowledge of where and when to look.

(Honestly, it’ll help if your neighbors turn off their holiday lights for a while, too.)

One of the best things about meteor showers is that you don’t need any special equipment to view them; your naked eye is actually ideal. While most astronomical events are localized to a single point or a narrow region of the sky, meteor showers create displays that extend everywhere the human eye can see from any point on Earth. In fact, the only thing that’s localized is where the meteors originate from: what’s known as the radiant of a meteor shower.

Perhaps surprisingly, the best location to watch is anywhere other than exactly at the radiant itself, because the meteors will all be traveling away from that location. Instead, the best viewing location is wherever the greatest dark area of visible sky happens to be, and to do it with as wide-field a view as you can obtain. For many, sitting in a reclining chair or even a lounge chair — with blankets and many layers, if appropriate — is the best way to take in as much of the sky as possible.

Figuring out exactly when to look is a little tricky, for three reasons that all go together.

- Most of the world is located in the Northern Hemisphere; at this time of the year, it’s difficult to find cloud-free skies at night, particularly at higher latitudes.

- The Geminids are prolific, but the meteors they produce are slower moving and less intrinsically bright as a result, so finding dark skies is key, and also increasingly a challenge, given the rise in light pollution.

- The Moon can be a major source of light pollution whenever it’s in the sky. However, on the night of the peak, December 13th-through-14th in 2023, the Moon phase will only be a thin, waxing crescent, and will set before the sky even fully darkens..

The clouds are a roll of the dice. If the weather cooperates, you’ll have a good show, but if it’s cloudy, you’ll have the same experience that many professional astronomers sometimes do of being “clouded out” of your astronomical hopes. The darkness of your skies is something for which you can plan ahead, as we’ve done an excellent job of monitoring where light pollution is most egregious versus where clear, dark skies are. While finding a pristine sky is incredibly challenging for most, the darker your skies, the better you’ll be able to see the fainter Geminid meteors.

Every single year for the past 15 years, the Geminids have peaked at over 100 meteors-per-hour at its most active, with this year’s predicted peak to reach approximately 150 meteors-per-hour, or roughly one expected meteor every ~24 seconds. The best viewing opportunity will come on the night of December 13/morning of December 14, with best viewing occurring from 10 PM local time onward. Your best bet is to take in a wide-field view of the sky from a dark area, and to worry more about the darkness/light pollution of the location you’ve chosen and cloud cover than about the Moon, as this year, the Moon will set before the meteor shower peaks.

The illustration above shows a visual comparison of what the night sky looks like with different amounts of light pollution. The Bortle scale — the dark sky scale used to quantitatively assess how light-polluted an area is — ranges from a completely pristine sky, which is rated “1,” up to the most brightly lit locations on Earth, like New York City, which is rated “9.” If you can find a location where the brightness is “5” or better (and lower numbers are better), you’ll have a show worth watching.

There’s a very popular myth that meteor showers arise from the tails of objects like comets and the volatile-rich asteroids. (You can even find this myth repeated on a few older NASA sites.) This isn’t true at all, however. Although it is true that

- comets and volatile-rich asteroids possess tails,

- and that comets and volatile-rich asteroids produce meteor showers,

these two facts are not related to each other.

When a comet or asteroid produces a tail, what’s happening is that particles are being heated and accelerated by the Sun. The spectacular sight of a tail, however, is because particles are being pushed away from the parent body itself and also away from the Sun. Importantly, these particles do not wind up in the same orbit as the parent body, meaning that when Earth crosses the orbit of the comet or asteroid in question, it doesn’t hit the particles that have been expelled in either the dust or the ion tail. Moreover, looking at the parent body of the Geminids — asteroid 3200 Phaethon — you can see that it not only doesn’t have a tail, but it also appears to be a relatively quiet body, with no coma or visible debris coming off of it at all.

Whereas most meteor showers originate from long-period comets, appearing most spectacular when Earth passes through the densest regions of the comet’s debris stream (i.e., closest to when the comet appears in our skies), the Geminids have no such constraints. Formed not from a comet but from an ice-rich asteroid — 3200 Phaethon — the Geminids get stronger every ~18 months or so, as that’s all the time required for Phaethon to complete an orbit around the Sun.

Along with January’s Quadrantids, the Geminids are the only named meteor showers to arise from an asteroid instead of a comet, with the tight orbit causing the meteors to move more slowly compared to the ones that originate from bodies that travel very far from the Sun. However, the fact that the Geminid debris stream thickens every time this short-period asteroid orbits the Sun gives the Geminids a chance to get more spectacular each and every year. Because of the way Earth’s orbit and this asteroid’s orbit line up, the Geminids get particularly strong on a triennial basis, with 2011, 2014, 2017, and 2020 all putting on stronger shows than average.

2023? It might be the best show yet.

The current record for meteor rates during the Geminids was set during the 2014 shower, where we more than doubled the predicted rate of ~120 meteors-per-hour, observing a whopping ~253 meteors-per-hour at its peak. This year, the typical estimate is that skywatchers will see ~150 meteors-per-hour at their peak, but a similar outburst could easily break the record. The peak rate of meteors, known as the ZHR (Zenith Horizon Rate), has never crossed the 300 meteors-per-hour threshold for the Geminids before. In fact, no meteor shower in the 21st century has achieved that milestone yet! If nature is kind to us, perhaps 2023 will be the year that we get there!

Of course, meteor showers fizzle, rather than sizzle, more often than not, which is part of the reason why the Geminids (and Perseids) are so spectacular: they’re reliable, year after year. The Moon won’t get in the way, other celestial events won’t interfere with this meteor shower, and the debris stream is so strong and robust that there’s no risk of a broken promise. The only thing that can stop you is the presence of clouds: the bane of skywatchers across the world. Even if it’s not a record-breaking show, it’s guaranteed to be a solid one.

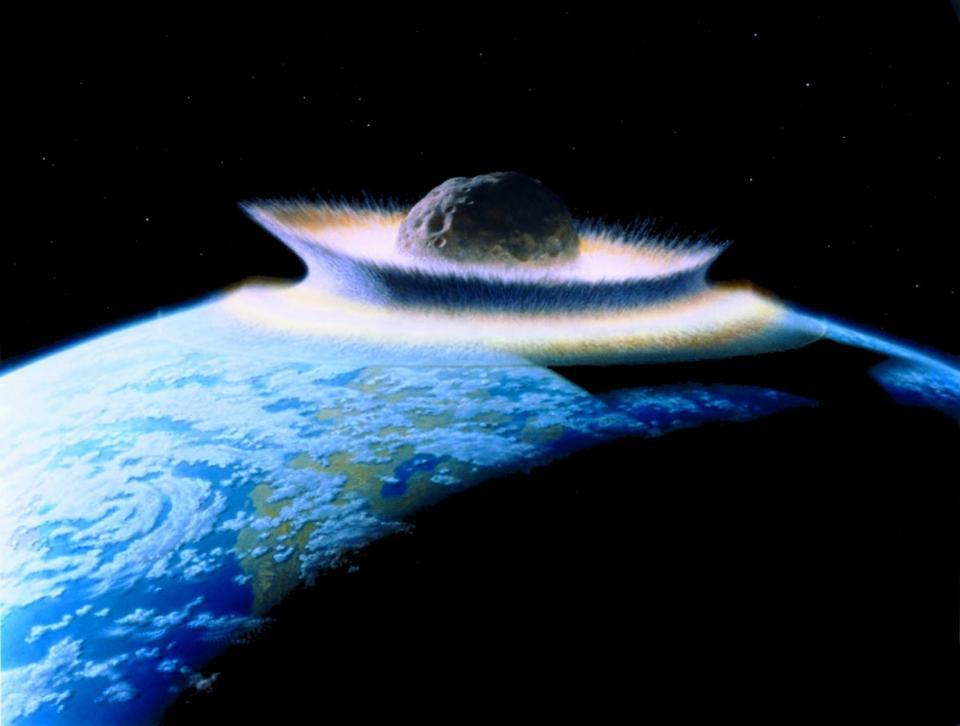

One of the best aspects of this year’s Geminids is that even though they may be the most prolific ever, at least so far, they should continue to strengthen throughout the century. As the large parent body of the Geminids, asteroid 3200 Phaethon, continues on its tight orbit around the Sun, it will continue to expel matter and be torn apart, bit by tiny bit. The asteroid is about the size of the one that struck Earth 65 million years ago, causing our last great mass extinction. But instead of colliding with us all at once, this ~6 km wide asteroid is slowly dissipating in the presence of the Sun, creating tails of matter and ions but also an ever-thickening debris stream.

With each mid-December that rolls past, Earth slams through that debris stream, creating a show that gets progressively more spectacular with each set of orbits that regularly tick by. While the Geminid meteor shower technically lasts for weeks, however, the peak remains narrowly collimated, meaning that if you want to see the biggest outburst and the most spectacular show, the best time to view it — far and away — is the one and only night of the peak. Over the past 18 years, the Geminids have regularly been one of the two best displays of meteor showers on Earth, and it’s eminently possible that 2023 will set a new record. The Moon, the Earth, and all of the other predictable conditions are just right for a spectacular show. If the clouds also cooperate on December 13 and 14, treat yourself to the greatest natural show of the year.