Physics Reveals What’s In Herculaneum’s Incinerated Ancient Scrolls

If you’re studying a long-lost culture, there’s hardly anything more tantalizing than having in-hand papyrus scrolls written by its citizens. What insights would these documents hold about who those people were? And there’s hardly anything more frustrating than if the scrolls have been burnt to such a crisp that straightening them out to read could cause them to crumble, lost forever.

This is just the situation papyrologist Daniel Delattre was in. In his case the scrolls are from the ancient Roman city of Herculaneum, and they were discovered about 250 years ago. The scrolls were written before Mt. Vesuvius’ catastrophic eruption in 79 A.D. when its pyroclastic cloud engulfed and killed the people living there and in Pompeii. In Pompeii, of course, citizens died encased in hot ash. For years no one realized anyone had even died in Herculaneum because there were no bodies—it turns out theirs had been completely vaporized by the 300-plus-degree heat.

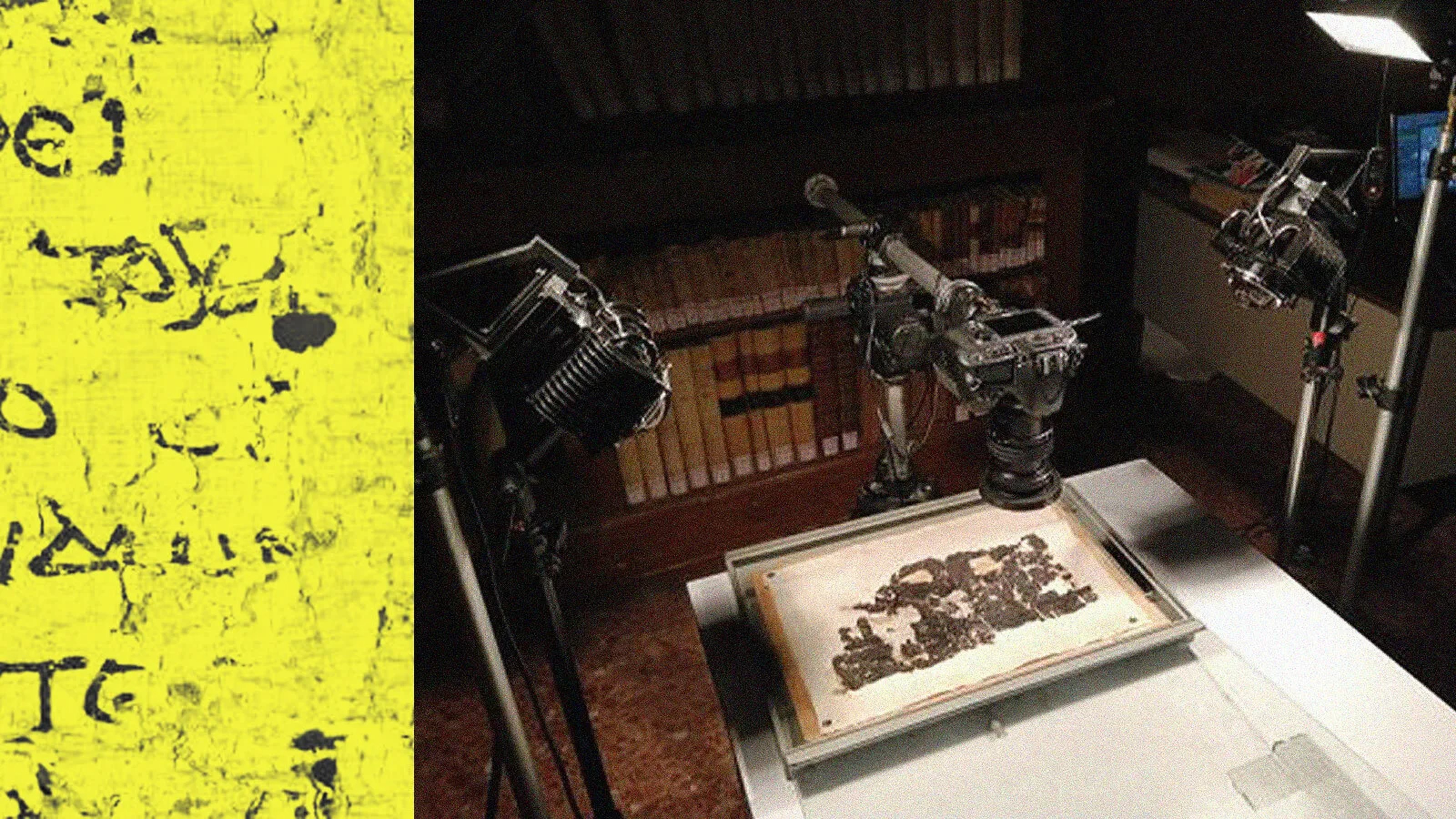

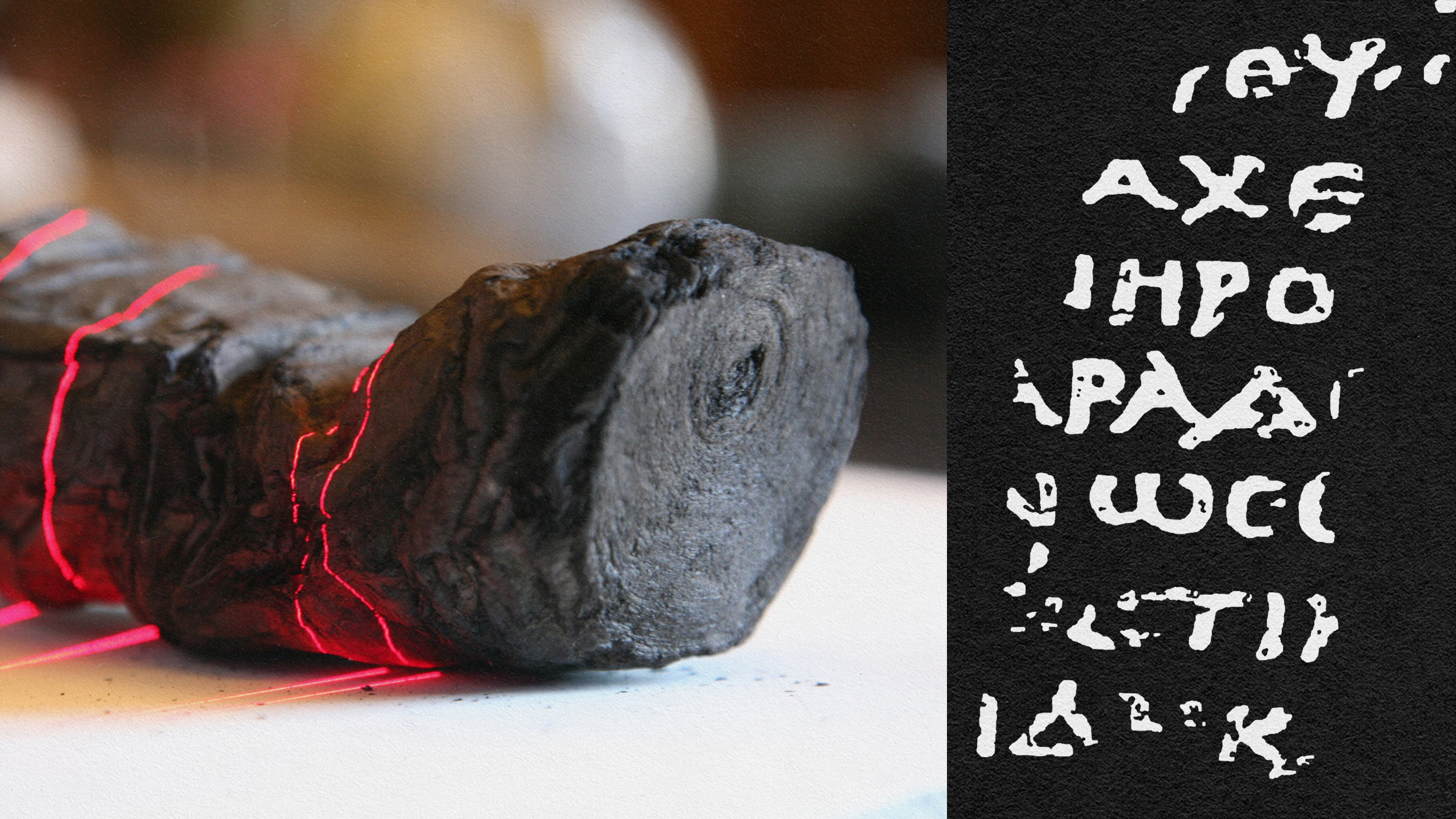

The scrolls are from Herculaneum’s library, and are so burnt they look simply like charred chunks of wood.

At first scientists tried to simply unroll a few of them, but they broke down during the process, leaving little bits of papyrus from which a handful of words could be read, and ashes.

In 2013 electronic engineer and physicist Vito Mocella got the idea to try scanning a scroll in a synchrotron, a type of particle accelerator. His thought was that the synchrotron could generate a coherent x-ray light that would allow them to see the letters inside the charred object. They ran a scroll through the European Synchrotron in Grenoble, France to generate a layer-sensitive x-ray image.

In a stroke of luck, the scroll’s authors had used a kind of ink that sits on top of the papyrus surface, creating a very slight relief from which characters can be made out, a tiny bit at a time.

While the contents of the scrolls haven’t been deciphered yet, work continues, and this is obviously an exciting breakthrough. Oddly, the very first pair of verbs Delattre and Mocelli read—according to this video from The Atlantic—were “cadrebbe” and “direbbe,” which translate to “would say” and “would fall.” The writer could well have been referring to the soon-deadly mountain towering over them.

Headline image: Joseph Wright of Derby