It Ain’t Easy Being Greece

It ain’t easy being Greece. Last year, the eurozone crisis had the country flirting with insolvency. Athens narrowly avoided being kicked out of the common currency. This year, it’s the refugee crisis.

Not that waves of rubber dinghies landing on Lesbos are a new phenomenon. For a number of years now, Greece’s islands have been stepping stones for huge numbers of migrants crossing from Turkey into Europe.

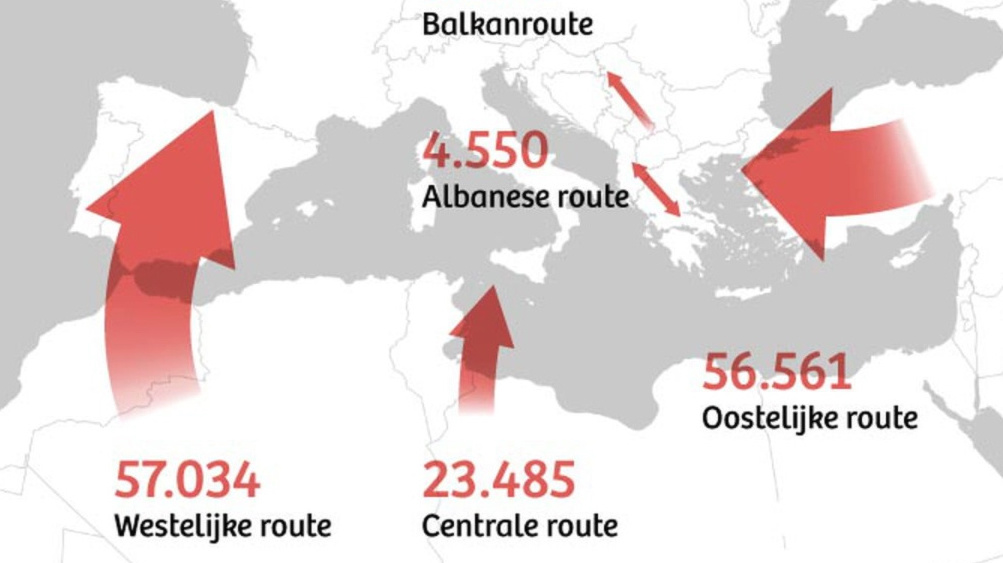

Typically, they move north to seek asylum in Germany, Sweden and the other promised lands of northern Europe. But that route has been blocked off this week, by a cascade of border closures, moving from north to south across the Balkans.

Austria was first to bar migrants from transiting its territory, quickly followed by Slovenia and Croatia, both also EU members, and Serbia and Macedonia, both outside the EU.

As a result, close to 14,000 refugees are now trapped at Idomeni, on the Greek side of the border with Macedonia, in conditions described by a Greek government minister as “atrocious”.

Germany’s chancellor Merkel has condemned the border closures, saying they put Greece in a very difficult position. She stated that a resolution to the crisis would need to come from the EU as a whole, not from disconnected measures by individual states.

The EU and Turkey are in fact finalising a plan that would send back all migrants arriving in Greece to Turkey. In exchange, the EU would take in an equivalent number of Syrian refugees currently living in Turkey.

But that’s not a done deal yet, so migrants are still streaming into Greece, and are now unable to move on. “If we don’t reach a deal with Turkey, Greece won’t be able to bear the weight for long”, Merkel said. Ankara, in any case, has said that the ‘one-in, one-out’ plan does not cover Syrian migrants already in Greece.

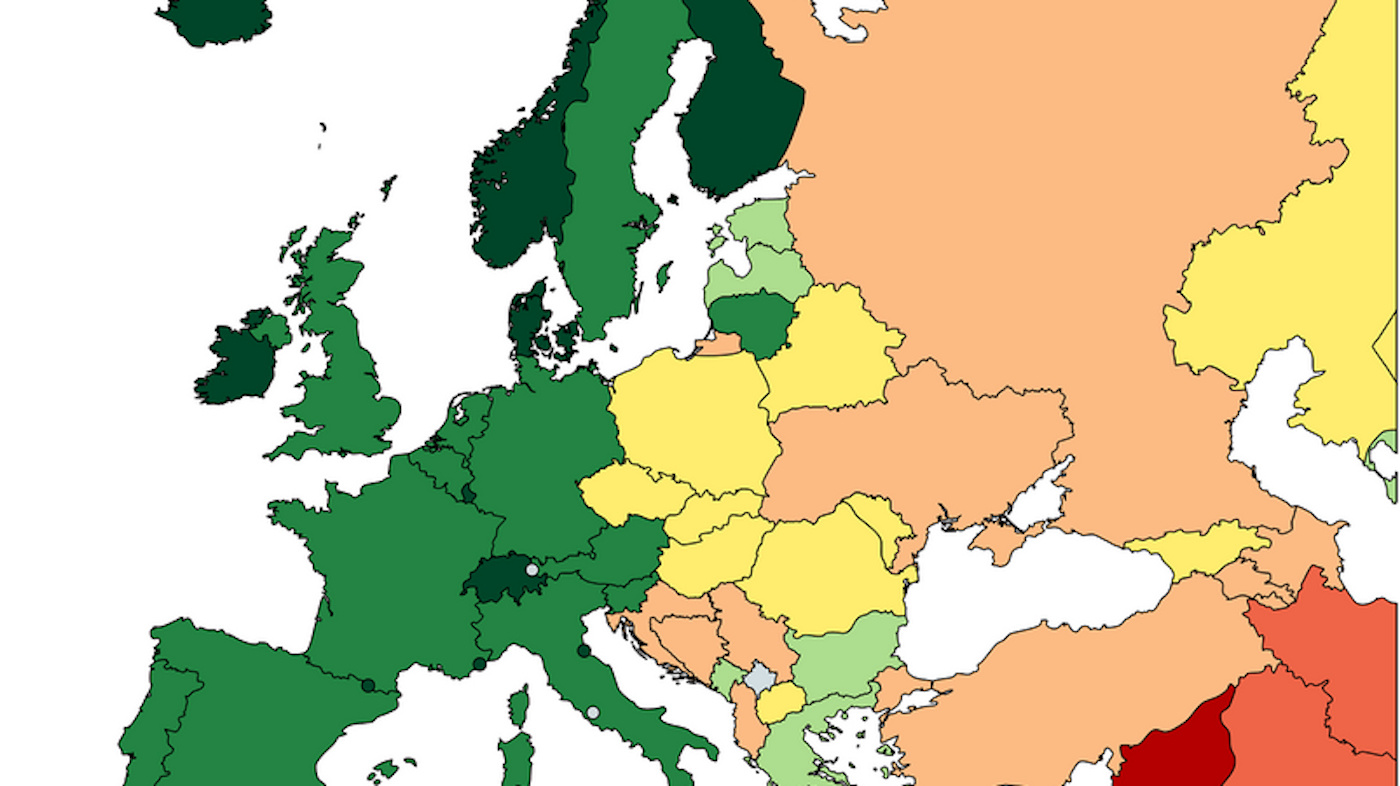

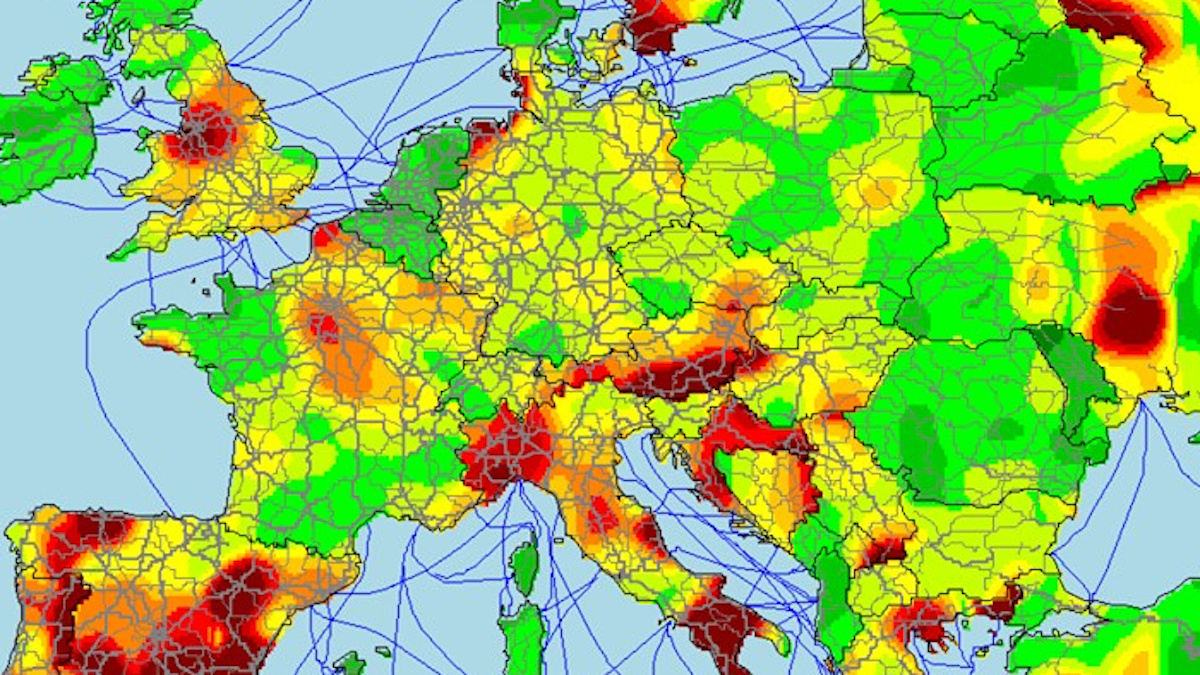

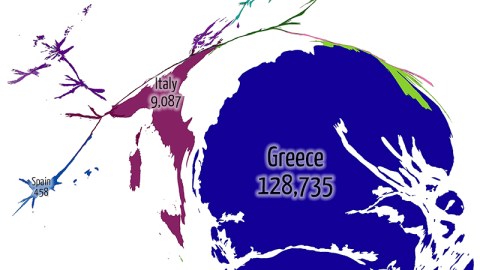

Is there a danger that Greece, impoverished by the eurozone crisis and strained by the refugee crisis, will collapse under its burden? Here are three maps that give an idea of the size of the problem. All three are cartograms, distorting the area of the countries on the map to reflect the number of refugees arriving by sea. The first one covers the period 2006 up to and including 2014.

Maritime migration clearly is a Mediterranean issue: there are no boat people landing on Europe’s Atlantic, North Sea or Baltic coasts. Italy was the favoured destination, with nearly a third of a million people arriving. Greece had less than 90,000 arrivals over the same nine years, Spain had just under 40,000 and Malta almost 14,000.

By 2015, the figures have exploded, and the stream has shifted. Migration to Spain and Malta has all but dried up; Italy is taking in a lot of people in absolute terms (almost 145,000 in a single year), but those figures are overshadowed by Greece’s – more than 750,000 arrivals just for 2015 alone.

The last map, based on figures for the first two months of 2016, shows the crisis lessening for Italy, but worsening for Greece, with almost 130,000 refugees arriving in January and February alone.

Will the closed borders keep potential migrants from making the dangerous crossing into Europe? Or will it turn Greece into Europe’s refugee dumping ground?

Maps created by Benjamin Hennig, Senior Research Fellow in the School of Geography and the Environment at the University of Oxford, and found here and here at Views of the World, his personal website, which contains a lot more cool maps.

Strange Maps #771

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.