Brexit, a Fairy Tale in Four Maps

In a happier, parallel universe, Brexit is a chart-topping boy band. In ours, the frivolous-sounding word is somewhat more portentous: it’s a portmanteau for the British Exit from the European Union. Brexit has never been closer than today. Except tomorrow, and every day after, until the much-anticipated referendum on the matter, perhaps as early as this June.

Why is the UK on this slippery slope toward the Union’s exit? And what does the rest of the EU think of the process?

“(T)he question of Britain’s place in the EU is about more than the precise restrictions to benefits for new migrants, or any commitment to cut back on excessive business regulations,” writes Lord Ashcroft in the introduction to “You Should Hear What they Say About You,” a survey conducted among 28,000 European voters by the controversial peer and entrepreneur’s own polling company.

The entire survey can be downloaded here at Lord Ashcroft Polls. Just scroll down here for the coolest bits — four volume-speaking maps.

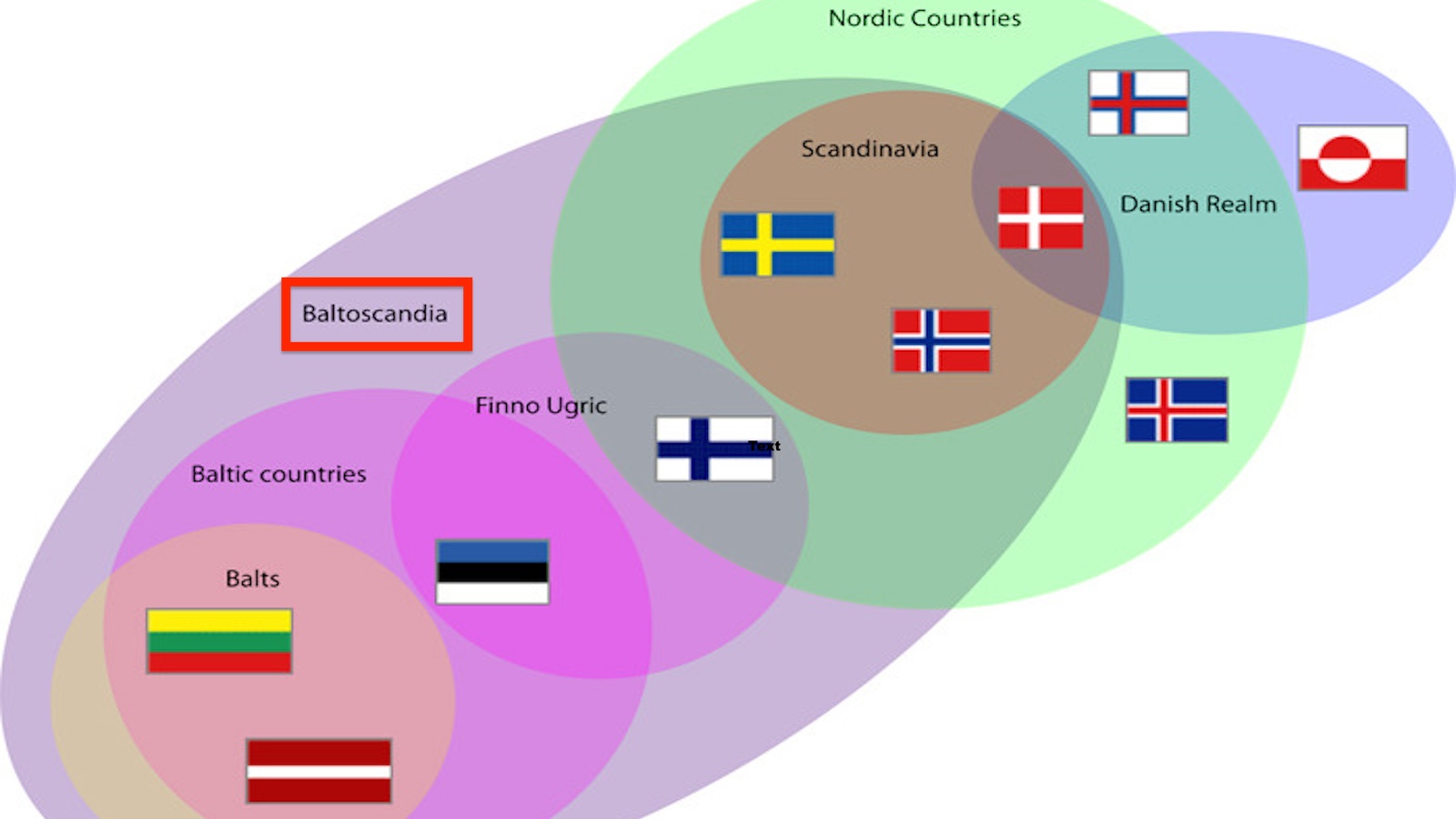

First, one showing the European Union and its “internal” borders. Connoisseurs of European geography will note that the EU is not Europe, and vice versa. Essential parts of Europe are whited out: Switzerland, much of former Yugoslavia, Norway, Iceland, and the entire former Soviet Union (with the exception of the Baltic states, all three happier under Brussels’ sway than Moscow’s). The implication of the map is that geography does not equal (political) destiny: Plenty of countries are European (in the geographic sense) without being EU members. So why couldn’t the UK — already shaded in a different colour – do the same?

The European Union’s explicit goal is to move toward “ever closer union” — three words that summarise exactly why many Brits want to get out of the club. They claim the UK signed up to a free-trade zone only, and was lured into a political project that wasn’t on the agenda back in 1973. But the EU is far from a close union. These four maps highlight four fault lines running through the Union. The first (top left) is the old Iron Curtain, dividing the richer Western member states from the more recent, still poorer Eastern ones. The second (top right) shows who’s in and out of the Eurozone. The UK, Denmark, and Sweden have opted out, and much of Eastern Europe has yet to converge enough to qualify for membership. The third (bottom left) separates large from small members (*). The last one splits (so-called industrious) north from the (reputedly indolent) south.

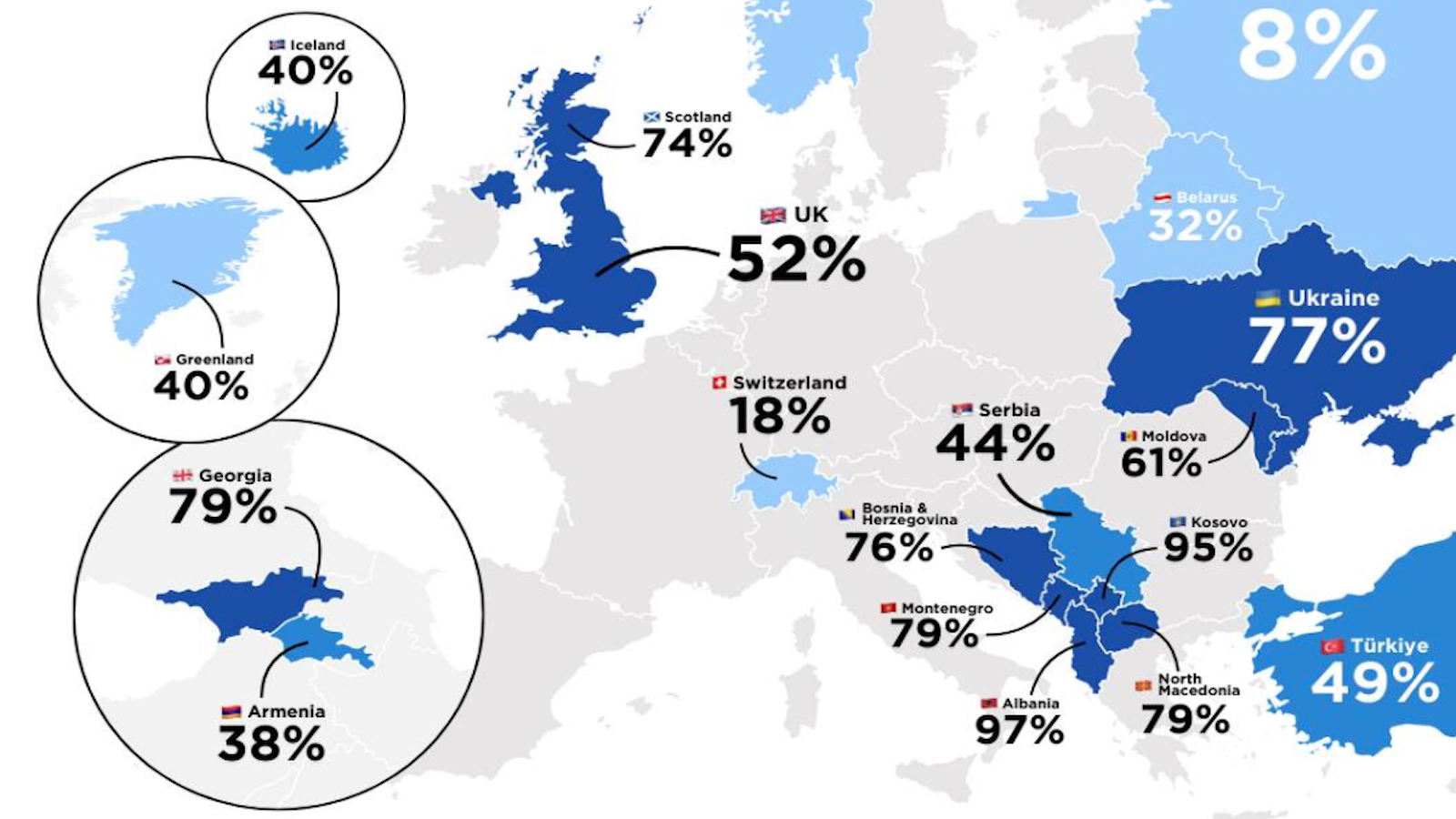

Only 52 percent of Brits have a positive attitude toward the EU, which augurs badly for the coming referendum — it could be a very close call indeed. But Britain is hardly alone in its ambiguous feelings for Europe. In Denmark and Austria, the EU also gets no more than a 52 percent favourable rating. The score is even lower in Sweden (51 percent) and dips below half in the Czech Republic (45 percent). Results in the Netherlands and Cyprus were hardly better (53 percent in both cases). What if similar referenda were held there? Big positives (>=70 percent) were only recorded in Malta, Spain, Poland, and Lithuania. Ah yes, one is inclined to think: net recipients of EU funds. One positive note from a pro-EU perspective: the Eurozone — in the vanguard of integration — is more positive toward the EU than the non-Eurozone countries: 65 percent vs. 58 percent.

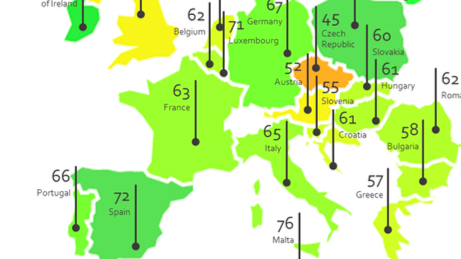

The paradox for British Euroskeptics is that they have a lot of friends in the rest of the European Union. Why not stay in the Union, and forge alliances to remake it more in their image? Perhaps because not everyone is so friendly to the exceptionalists from perfidious Albion. This map identifies the UK’s potential allies and enemies in the fight for the future of the EU.

The “Friends and Family,” most favourable to both the EU and the UK’s membership thereof, are a mainly small and diverse band of countries, from Portugal and Malta over Poland, Lithuania and Estonia to Ireland. Diverse: good. Small: bad. Next in line is the “Willing to negotiate” group — neutral to the UK, but with similar frustrations of their own. Important members: France, Italy. Smaller ones: Belgium, Netherlands, Denmark, and Sweden. Five smaller countries (Cyprus, Hungary, Czech Rep., Slovakia, Latvia) are “Ready for reform”: also neutral toward the UK and discontented with the EU, but positive on free movement. These guys are ready to play ball.

After three groups in the plus column, here are three in the negative one. Austria, Finland, Greece, and Slovenia are “Not in the mood”: unfavourable towards both the EU and the UK. For Bulgaria, Croatia, and Romania, “It’s personal.” They like the UK more than they like the EU — they’re just in it for the travel. “Take it or leave it,” say Luxembourg, Spain, and — crucially — Germany. These countries are neutral toward Britain, very positive about EU membership and very unsupportive of UK demands.

Strange Maps #766

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

* The map legend has mixed up the > (larger than) and