Why the USSR and China fell behind the US in the Chip Cold War

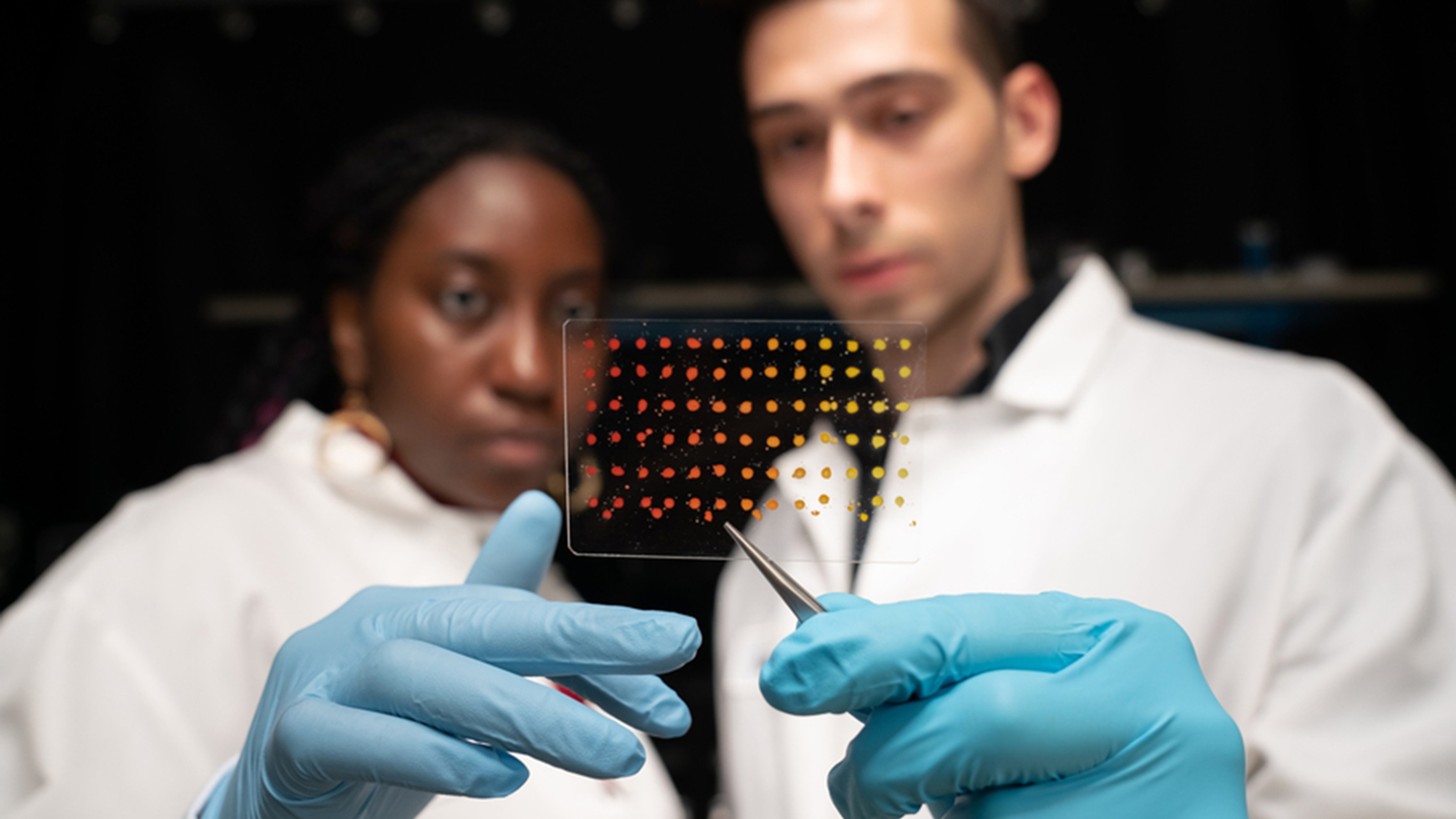

- The global microchip industry is at the center of geopolitical tensions between the US and China, with Taiwan’s dominance in semiconductor production playing a crucial role.

- China’s efforts to develop its semiconductor industry faces challenges similar to those encountered by the Soviet Union during the first Cold War, including difficulties in talent retention and economic policy constraints.

- The US is reshoring microchip manufacturing to reduce dependence on foreign suppliers, but faces significant obstacles as well.

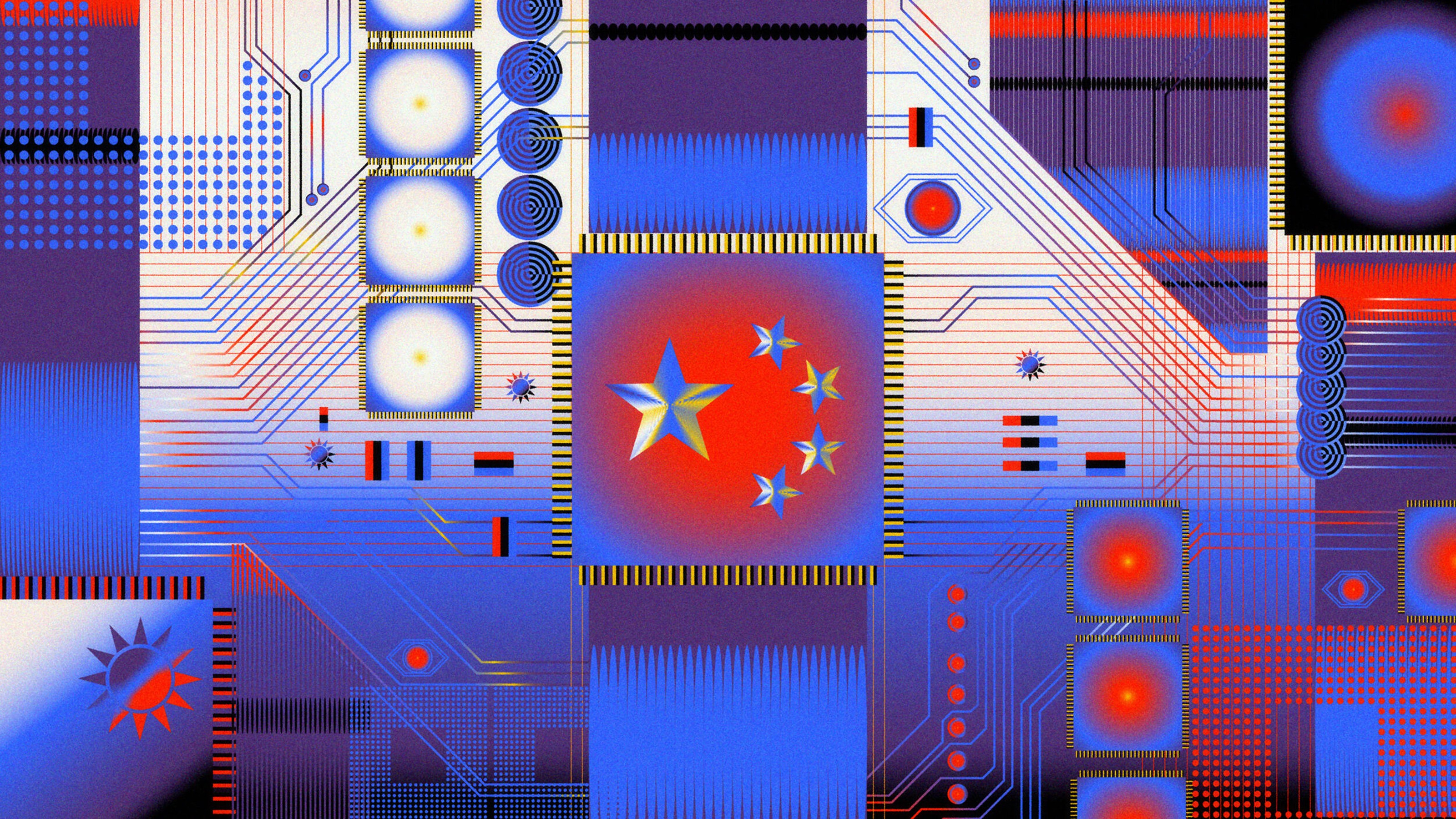

In April 2024, Chinese President Xi Jinping hopped on the phone with Joe Biden to condemn the American president’s plan to ban the export of advanced microchips and chip-related technologies to the People’s Republic of China. The ban struck Xi as little more than a geopolitical dig, a move to “suppress China’s trade and technology development” that – if carried out – would only serve to escalate the ongoing Cold War between Beijing and Washington. Beijing, he promised, would not “sit back and watch.”

What this threat entails is anyone’s guess, but many experts suspect it involves Taiwan. Decades of investment and strategic industrial policies have helped the island nation develop into the single most important player in the global microchip industry. The manufacturing giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) currently produces a whopping 92% of the world’s most advanced semiconductors, a technology without which every state-of-the-art phone, computer, television, car, MRI scanner, and advanced missile on the planet would cease to function.

Despite building a competent technology sector of its own, and poaching Taiwanese talent with high wages and tax benefits, China’s domestic microchip industry cannot compare to its southern neighbor — and, some believe, the closer this neighbor allies itself with the US, while cutting off Beijing, the greater the risk that China will seek to reunify the island with the mainland through force.

During the first Cold War, the battle over developing advanced semiconductors — and the myriad of devices they could be used for — was fought primarily between the US and the USSR. The results of this battle, in which the US and Silicon Valley emerged victorious, inform not only Beijing’s efforts to challenge American hegemony but also Washington’s attempts to reshore microchip manufacturing at a time when Taiwanese national security has become increasingly uncertain.

Lessons from Zelenograd

In 1962, Nikita Khrushchev met with Joseph Berg and Philip Staros, two engineers from Silicon Valley who defected from the United States to help the Soviet Union develop a center for innovative microtechnology modeled after its American counterpart. Despite its lofty ambitions, the center — located in a secretive Moscow suburb called Zelenograd — never managed to rival Silicon Valley. Instead of promoting original research, its resident scientists simply copied technology smuggled out of California, meaning they always stayed one step behind the very people they wished to overtake.

“The USSR likely struggled to replicate US semiconductor tech due to their astronomical rate of chip innovation,” Ethan Chiu, a global affairs and history student at Yale University serving as a China and Taiwan Studies Intern at the Council on Foreign Relations, tells Freethink. Moore’s Law — the observation that the number of transistors on new chips doubles about every two years — explains why the USSR and China have had such a hard time catching up with the US and Taiwan. As if playing catch-up with exponential progress wasn’t difficult enough, the CIA sabotaged Zelenograd’s efforts at reverse engineering by ensuring many of the American chips they obtained were often faulty and malfunctioning.

Another reason why the Soviet Union’s chips always lagged behind the United States is economic policy.

“The US had a vast civilian market,” Chris Miller, historian and author of Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology (2022), tells Freethink, “which was critical because semiconductor economics requires massive scale, which in turn enables larger investment in R&D. The US also built efficient global supply chains, taking advantage of low labor costs in Southeast Asia as well as technical expertise in Europe and Japan. The Soviets had neither. They were focused from the earliest days on copying US technology. They succeeded in copying, but copying left them behind the curve because Silicon Valley made such rapid progress.”

“The United States,” adds Erik Peinert, an assistant professor of political science at Boston University and co-author of a recent report on the reshoring of American microchip manufacturing for the American Economic Liberties Project, “had access to world markets beyond their own borders, which had a high demand for chips during the Cold War, whether for military or commercial purposes. The USSR only had the Communist bloc.”

Instead of cultivating civilian and commercial demand for microchips east of the Iron Curtain, the Soviet military was always Zelenograd’s primary customer. This dependence helps explain why Russia is no longer a key player in the global production of semiconductors. When the Soviet military dissolved in 1992, Zelenograd followed suit. Its fabs — manufacturing plants where raw silicon wafers are turned into integrated circuits or ICs — were shut down, and the closed-off city was gradually reopened to the public.

“The collapse of the Soviet Union,” Hermann Aubié, a professor at the University of Turku’s Centre for East Asian Studies who has studied the geopolitics of microchip manufacturing, tells Freethink, “disrupted its scientific and industrial base, leading to brain drain and lack of investment in R&D and global supply chains.” Stepping away from microtechnology, the Russian Federation went on to prioritize other sectors such as energy and raw materials. The Kremlin now relies heavily on semiconductors made by US-allied partners like Taiwan and South Korea, much to the detriment of its military capabilities. As Chiu points out in one of his articles, only 5% of Russian weapons used in the Syrian Civil War were precision-guided, while a large number of the semiconductors used in Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine were salvaged from dishwashers and refrigerators.

China’s Great Leap

In China, political persecution greatly hindered the development of the country’s technology sector. During the 1960s and early ‘70s, Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution not only led to the imprisonment or execution of countless talented engineers, scientists, and inventors, but also drove many — including future TMSC founder Morris Chang — to flee to the US, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, boosting their technological potential in the process.

When the Cultural Revolution subsided and Mao was succeeded by Deng Xiaoping, China’s nascent semiconductor industry couldn’t hold a candle to that of its rivals. Too far behind to innovate domestically, the People’s Republic took a page from the Soviet playbook, replicating US, Taiwanese, and Japanese technology as the gap between them grew bigger and bigger.

But while the Soviet Union eventually dropped out, China has managed to stay in the race. This was partly due to Beijing’s acceptance of a more open economy after Mao’s death.

“The Soviets succeeded at certain military technologies but struggled to make advanced chips at scale,” says Miller. “Many of China’s advancements, meanwhile, have come from private companies.” If limited privatization previously enabled Chinese tech firms to make headway, it should come as no surprise that Xi’s recent pushback against private enterprise is once again hindering China’s potential for growth: “Now the state is becoming more involved in the technology sector, and this risks replicating some of USSR’s pathologies.”

Studies of China’s microchip industry suggest that the benefits of state subsidies, tax cuts, and large-scale poaching of Taiwanese and American-educated talent are being offset by corruption, overregulation, and mismanaged resources, resulting in brain drain out of China, as well as the liquidation of major chip manufacturers like Tsinghua Unigroup, which filed for bankruptcy in 2022.

Then again, the Chinese economy has taken experts by surprise before, and Chiu notes that modern-day China is in a much better position than the Soviet Union or Russia ever were. “China’s present-day chip industry,” he explains, “is less centralized and replication-reliant than the USSR’s. Its economy is much closer to the size of the US economy than the USSR’s economy ever was, enabling much more Chinese investment (tens of billions) into the chip industry. While there is a lasting stigma that Chinese products are cheap, poor quality, and mass-produced, Chinese innovation has actually taken off over the past few years.”

Additionally, he notes that the chip bans imposed by the Biden administration could actually backfire, by driving China to invest more heavily in domestic chip development and manufacturing.

“China has also leveraged talent poaching more effectively than the USSR, stealing highly-trained semiconductor process engineers from Taiwan by paying them high salaries,” Chiu says. “In fact, China’s most successful semiconductor manufacturing company, SMIC, was founded by a Taiwanese entrepreneur and is so advanced largely because of Taiwan-directed talent poaching efforts.”

A new Cold War

Zelenograd’s legacy should serve as a warning to not just Beijing, but Washington as well. Although the US still contributes large amounts of funding and research, and accounts for the majority of chip sales, the country’s share of global manufacturing has been in decline ever since it began offshoring production to Southeast Asia in the ‘70s and ‘80s, falling from 37% in 1990 to just 12% today. This means that, at the end of the day, the US is in certain ways as dependent on foreign technology as are Russia and China, and perhaps even more so considering how many homegrown consumer goods — from iPhones to Teslas — would disappear from the market should something happen to the Taiwanese firms that provide their all-important chips.

Calls to reshore microchip manufacturing have been on the rise for years, and not just because of risks to Taiwanese security. As Chiu points out, the island faces plenty of other threats that are unrelated to Beijing’s quest of reunification, such as brain drain, energy shortages, and climate change. Peinert identifies additional motivations for reshoring, including increased demand for microchips in the US computing and automotive industries, as well as fab closures resulting from lack of global investment and supply chain issues left over from the coronavirus pandemic.

Mitigating the risk of trade between the US and Taiwan being disrupted is a popular policy, but reshoring microchip manufacturing will be no easy feat, despite huge subsidies offered for it in the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act. “There is definitely an uphill battle for the American market to see operating fabs directly as profitable,” warns Peinert, “not only because they are competing with heavily subsidized foundries and fabs abroad, but also because fab-less American firms are indeed much more profitable than any of the firms that do operate their own fabs.”

“Reshoring manufacturing to the US is expensive,” agrees Aubié, “making it difficult to compete with lower-cost production in Asia.”

“As the US considers certain semiconductor development pathways amidst massive federal semiconductor investment,” writes Chiu, “China’s approach to building a domestic semiconductor industry offers cautionary tales in talent management, overregulation, and corruption that the US should avoid.”

Instead of building US-based manufacturing infrastructure from the ground up, he argues that Washington ought to try to gradually expand Taiwan’s industry onto American soil. “The US,” he continues, “should seek to make building TSMC semiconductor fabs in the US as economically profitable as possible. TSMC generates most of its revenue from US companies, and the US could push private sector corporations and investors to pressure TSMC to diversify its advanced semiconductor fabs to the US.” To make this possible, he suggests expanding the funding made available through bills like the CHIPS Act to more broadly include Taiwanese firms, thus motivating companies like TSMC to further invest in the US.

In other words, the US government could compete with China in poaching Taiwanese talent and resources, reshoring manufacturing without isolating its allies and trading partners.

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.