627 – Holy Rock! Gibraltar, the Mother of All Territorial Disputes

Just our luck… the only part of the UK with tight border controls. The picture on the front page of Private Eye shows a long line of cars queueing to get into Gibraltar from Spain. Other images on the cover of the August edition of Britain’s leading satirical magazine poke fun of Labour leader Ed Milliband and Prime Minister David Cameron, all under the headline: It’s the silly season! Spain begs to differ. It is deadly serious about Gibraltar, and the tightened controls at the border this summer, causing traffic jams up to 7 hours long, served as proof of her determination.

___________________________________________________________

Gibraltar – just another silly-season story, or a dispute only a few incidents away from real conflict?

___________________________________________________________

Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy’s center-right cabinet was protesting what it sees as the illegal dumping, in July, of 50 concrete blocks in disputed waters off the British possession. Gibraltar claims the artificial reef would encourage sea life; Spain says it will tear up Spanish fishing nets. Gibraltar says Spanish fishing boats should use hooks instead of nets. And Spain says the blocks are outside the area it recognises as Gibraltar’s territorial waters anyway. And so on. But Rajoy’s ultimate goal remains the same as that of every Spanish government since 1713, when the Treaty of Utrecht confirmed in perpetuity Britain’s dominion over the Rock: its return to Spain.

Frustrated by the failure of several sieges and blockades, that desire has come to define Spanishness itself: “There cannot be a Spaniard worthy of the name, who can write, without blushing, that Gibraltar is not part of Spain”, said Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz, president in exile of the Spanish Republic (1940-’45).

So while the Gibraltarian standoff was quickly reduced to a silly-season headline in the rest of the world, on the ground it took on the air of a serious spat just one or two accidents away from full-blown conflict. Madrid’s go-slow border checks – officially to combat tobacco smuggling – may soon be replaced by a €50 border levy. On top of that, Spain may close its airspace for direct flights to the British overseas territory.

___________________________________________________________

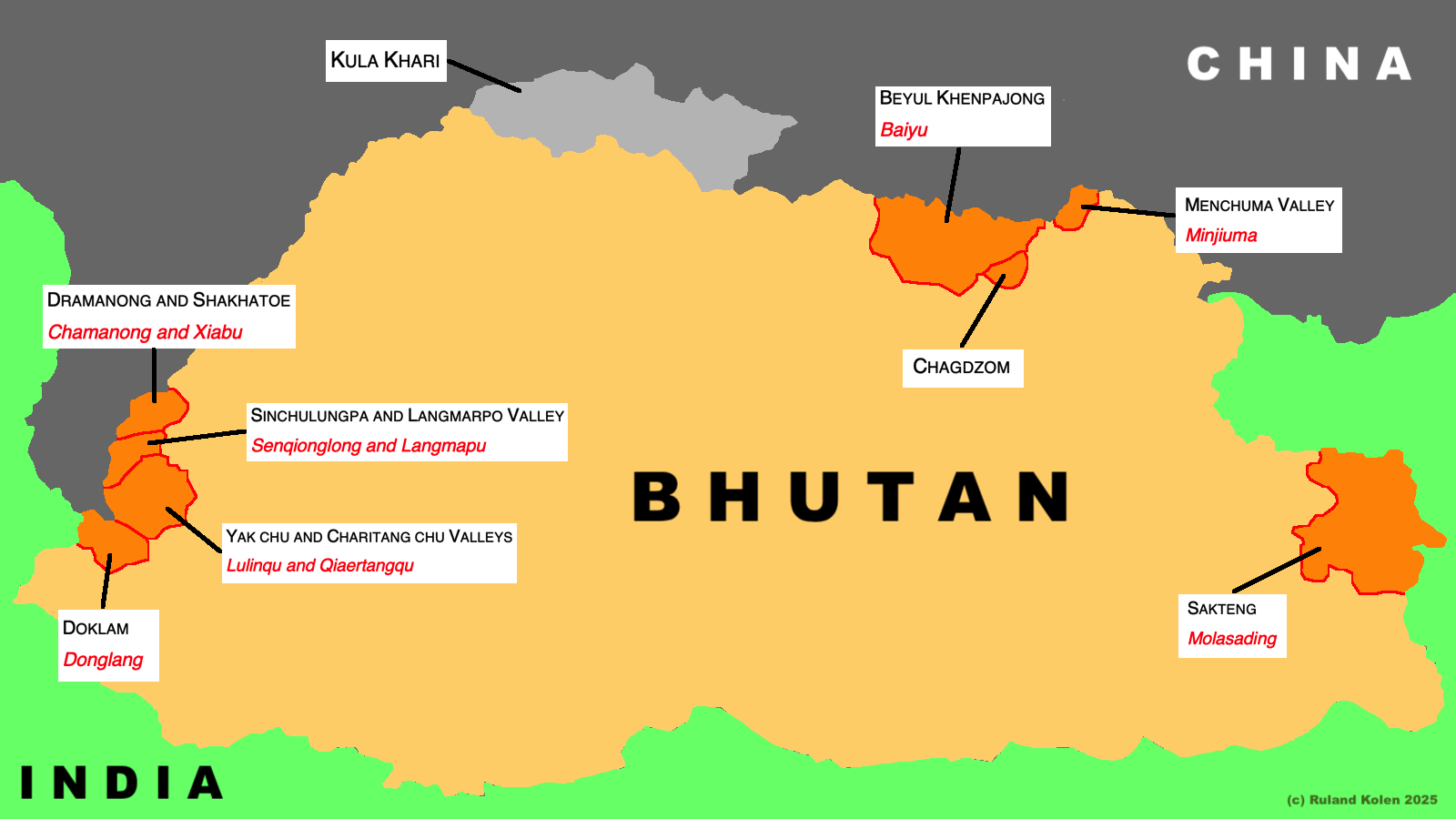

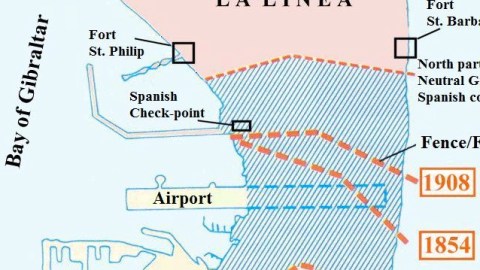

Dotted lines demarcate British claims, the orange zone inside Gibraltar’s port denotes the area of British sovereignty recognised by Spain.

___________________________________________________________

In retaliation, Britain sent HMS Westminster on a ‘scheduled visit’ to Gib, and requested the European Union to examine the legitimacy of Spain’s tightened border controls. The prospect of EU monitors on a fact-finding mission to a 300-year-old dispute between two member states adds to the atmosphere of Operettenkrieg[1] surrounding the conflict, as does the diminutive size of the territory in dispute [2].

To the Spanish and British governments both, the sabre-rattling over Gibraltar provided a distracting burst of patriotism, directing attention away from the Bárcenas bribery scandal and a severe case of midterm blues, respectively. But the standoff was more than a recurrent serpiente de verano[3]. Gibraltar is Spain’s oldest unhealed war wound, a symbol of its dysfunctional relationship with Britain, and a disheartening lesson in the persistence of territorial grievances.

Geology predestined Gibraltar to greatness. Half the territory is taken up by the Rock of Gibraltar, a 1,400-foot-high, cave-riddled limestone monolith that is the only landmark for miles in either direction along the coast. Those caves have yielded 28,000-year-old Neanderthal bones, the youngest known finds; perhaps this natural fortress is where humanity’s other species, decimated by the onslaught of Homo sapiens, came to die. From the top of the Rock, you can see – and if the wind blows north, smell and hear – Morocco, only 14 miles across the Strait of Gibraltar. Sitting at the crossroads of the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, and Africa and Europe, this tiny peninsula acts as a geopolitical safety catch.

To the Romans, who called it Mons Calpe, it was one of the Pillars of Hercules, marking the edge of the world. Its present name derives from Tariq bin Ziyad, the Muslim general who took the Rock in 711 AD as a prelude to his conquest of the Iberian peninsula. The other Pillar of Hercules, on the African side of the Strait, was renamed Jabal Musa after Tariq’s commander Musa bin Nusayr. Both pillars are on the Spanish coat of arms [4], but in a liminal torment that is Sisyphean rather than Herculean, the southern rock also eludes Spanish control: it is situated just west of the Spanish exclave of Ceuta, Madrid’s own geopolitical safety pin, across from Gibraltar.

Local history, and the region’s overlapping territorial claims, are riddled with such doublets. Recalling the onomastic quarrel over whether to call the body of water that separates Persia from Arabia the Persian or the Arab Gulf, the disputed waters to the west of the Rock to Anglophones are the Bay of Gibraltar, and in Spanish the Bahía de Algeciras, after the Spanish city on the opposite side of the bay [5]. And yet the comarca [6] surrounding the peninsula is still called Campo de Gibraltar. In fact, the town of San Roque, refounded by Spanish exiles from Gibraltar after the British takeover, retains the official city records of Spanish Gibraltar, flies a flag that is identical to British Gibraltar’s (save for the addition of a Spanish crown), and to this day maintains that it is ‘Gibraltar-in-exile’. San Roque, the name of which coincidentally translates as ‘Saint Rock’, is the original refugee camp as political weapon, designed to keep the resentment over the dispossession alive even centuries after the fact.

All of which might seem a bit pointless in light of the more benign invasions and counterinvasions between the former sworn enemies. There was a time when a state of war between Spain and England seemed natural, inevitable: two naval powers vying for supremacy in America, one the guardian of Catholic orthodoxy – Spanish Inquisition, anyone? – the other the champion of the Protestant cause. The great legacy of that rivalry is the as yet surviving demarcation of the New World in Anglo and Latino halves. Both countries are former empires now, however, and the only Armada sailing up the Thames these days are the droves of of Spanish jobseekers fleeing 57% youth unemployment at home. Spain meanwhile is home to over 500,000 British ex-pats, enjoying the fabulous supplies of sun, sea and sangria that the Costas have to offer.

But as the corrosive power of the economic downturn continues to eat away at the cohesive powers of the European Union, many in Spain increasingly resent the wealthier norteños in their midst as a cause of inequality rather than a solution. Higher taxes are driving many back home, to Britain, Germany and elsewhere. It is no coincidence that one of the measures the Rajoy government announced over the Gibraltar row was the investigation by Spanish tax authorities of the properties owned by Gibraltarians in Spain, or that Foreign Minister José Garcia-Margallo hinted at the possibility of new laws that would force the Gibraltar-based online gaming industry to have its servers in Spain, making them liable to Spanish taxes. “The party is over”, Garcia-Margallo said, referring to what he considers the all too conciliatory stance towards Gibraltar of the previous Spanish government.

___________________________________________________________

An overview of British encroachment along the Gibraltar peninsula. Hence the Spanish refusal to consider the current demarcation as a definitive border.

___________________________________________________________

From his hardline perspective, it is obvious that Britain has systematically abused periods of turmoil to extend the reach of its colony. The 1713 treaty only gave the British dominion over the town, castle, port and forts of Gibraltar. In 1938, while Spain was in the throes of civil war, they built an airport in a neutral zone on the isthmus on land they claim de facto belongs to Gibraltar, due to long-standing occupation. That neutral zone is now divided by a fence, which the Spanish refuse to acknowledge as the border. A similar conflict over the extent of Gibraltar’s territorial waters in bay is the root cause of the tensions that led to Gibraltar’s creation of an artificial reef – more a demarcation of territory than a gesture of fish-friendliness.

Ultimately though, and in spite of protestations to the contrary and all the red, white and blue bunting in the world, the fate of Gibraltar lies with Spain. Geographically and numerically, it is the obvious candidate for control over the peninsula. Unfortunately, there are more similarities between Gibraltar and the Falklands than between the Lincoln and Kennedy assassinations. Argentina and Spain both keep repeating how historically unjust, how geographically illogical and how politically untenable the British presence on their shores is. Neither is focusing its irredentist energies on their obvious target: the British subjects occupying their stolen lands. In both cases, their numbers are so few that the goodwill – not to mention the intermarriage – created by unrestricted access would tilt public opinion, slowly but surely, away from distant Britain, and towards integration with their next-door neighbour.

It seems so obvious a solution that there must be ulterior motives for the continued harassment of fellow EU citizens. How’s that scandal going, Mr. Prime Minister? Oh, and yes: you’ve made it to the end of a piece about Gibraltar that doesn’t mention a single Barbary macaque [7].

The Private Eye front page taken from the magazine’s cover archive. For a good overview of the background to the current conflict, see this post on the blog La Vida Alcalaína, also the source of the map of the disputed waters. Map of the peninsula found here at Wikimedia Commons.

___________________________________________________________

[1] Literally ‘operetta war’. According to Duden, Germany’s authoritative dictionary, Operetten– is often used in German as a prefix to denote someone or something rather pompous and self-important, yet not taken very seriously. See also: Operettenfußball, Operettenkönig.↩

[2] At 2.6 square miles, Gibraltar is about 11 times the size of the Mall in Washington DC, or just over twice the size of the City of London. ↩

[3] Summer snake, as the Spanish would call a silly season story. ↩

[4] Emblazoned with the motto Plus ultra – There is more beyond. ↩

[5] Algeciras is of course the Spanish spelling of the Arabic al Jazeera. ↩

[6] A Spanish administrative division comparable to a county. ↩

[7] Except, of course, that one. Darn. ↩