Occupy MoMA: Diego Rivera’s Populist Murals Reunited

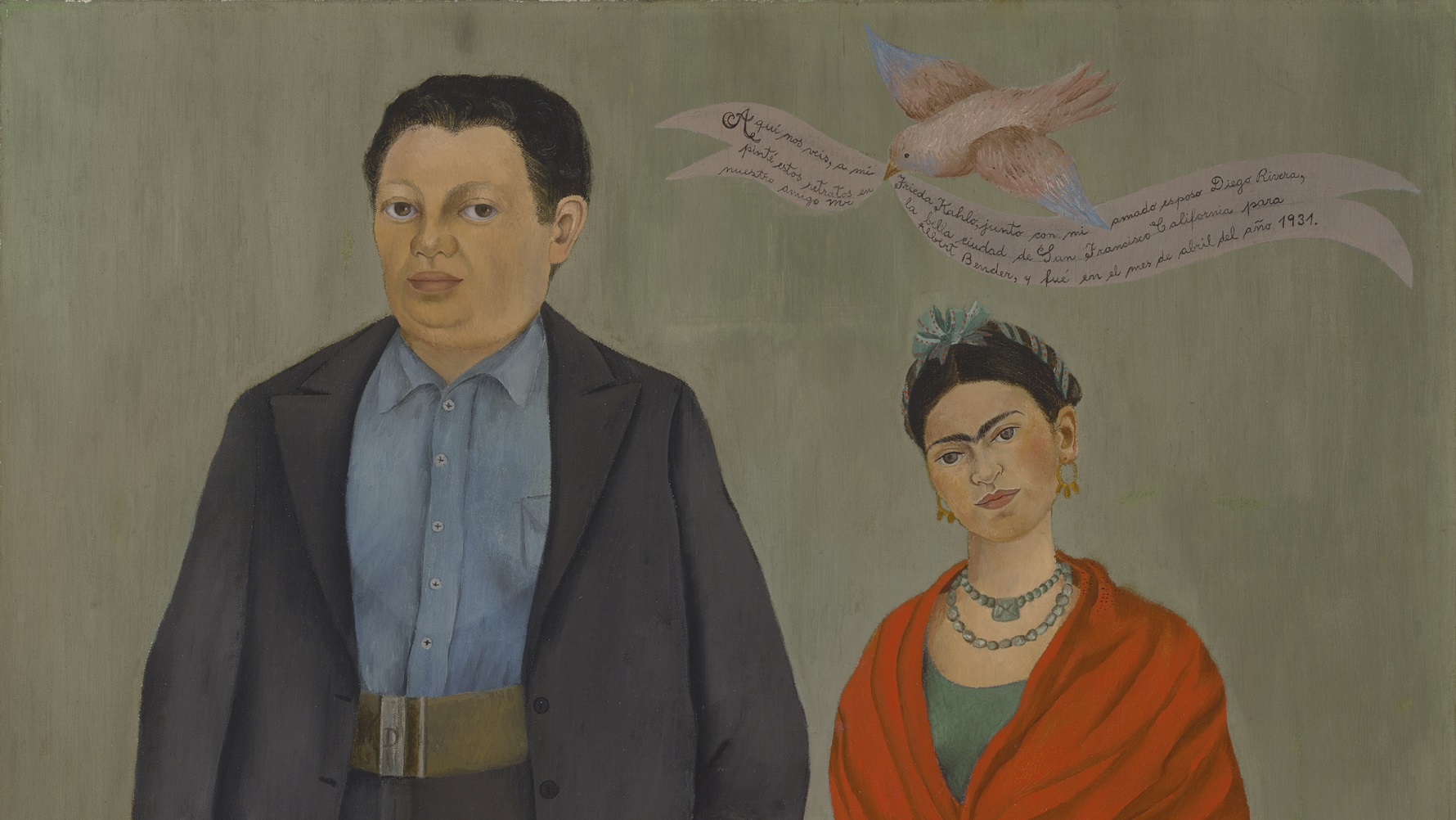

During his lifetime, Diego Rivera stood as one of the most important and controversial artists in the world. Today, thanks to the international feminist phenomenon of Frida Kahlo (who stood in her husband’s considerable shadow while alive), Rivera finds himself, at best, “Mr. Frida Kahlo” and, at worst, the philandering lout who only added emotional pain to Frida’s physical suffering. Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York through May 14, 2012, reminds us of the artistic genius and political passion that attracted both Kahlo and patrons to Rivera’s art. As the Occupy Wall Street movement continues to find venues to occupy around the world, it seems only fitting that Rivera’s murals first created for a MoMA retrospective in 1931—as the Mexican Revolution and Great Depression weighed heavily on the world—reunite to inspire a new generation of revolutionaries facing a new time of economic turmoil.

Along with José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, Rivera led what is now known as the “Mexican Mural Renaissance,” when the politics of the day found themselves written on the wall in paint in symbolically subtle and not so subtle ways. The Mexican Communist Party expelled Rivera from their ranks in 1929, but he never renounced his Socialist ideals. Even when the promise of patronage in the United States beckoned, Rivera painted his politics, often in the most awkwardly non-Socialist places. In 1930, just a year before the MoMA retrospective, Rivera painted murals for the San Francisco Stock Exchange. In 1932 and 1933, right after the MoMA show, Rivera painted Detroit Industry, a 27-panel tribute to the human side of Henry Ford’s motor company that survived attacks for decades thanks to the protection of patron Edsel Ford and a sign imploring viewers to think about Rivera’s talent and not his “detestable” politics. The highlight (or lowlight, depending on how you look at it) of Rivera’s American adventure came when he painted the mural Man at the Crossroads for Nelson Rockefeller’s Rockefeller Center in 1933. When Rockerfeller (who originally wanted Henri Matisse or Pablo Picasso for the project, but both were unavailable) asked Rivera to remove a portrait of Vladimir Lenin from the mural, Rivera refused and Rockefeller had the mural destroyed (or at least covered over). Rivera took his pay and his paint and returned home to Mexico, where he repainted the mural—Lenin included—calling it Man, Controller of the Universe.

The MoMA show catches Rivera at the crossroads, when the tension between his painting and politics made him simultaneously famous and infamous. Despite the drama, Rivera remained the controller of his universe and never shied away from the spotlight, even when it began to burn him. These reunited murals (no small task, considering the fact that they’re painted on reinforced cement) reinforce the role Rivera paid in picturing the revolutions swirling around him and cement his central position in the spirit of that time—a spirit that might be breathing once more today.

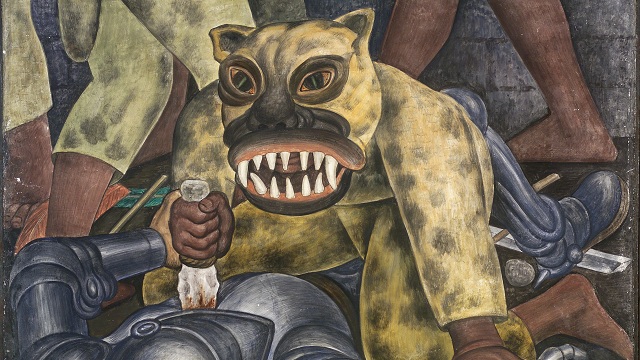

In Agrarian Leader Zapata, Rivera memorializes Emiliano Zapata’s contribution to the start of the Mexican Revolution in 1910. (Click on the mural titles to go to their coverage on the MoMA’s extensive, educational, and interactive site for the exhibition.) Zapata stands at the front of a column of farm tool-wielding peasants as he literally steps over the dead body of a plantation owner—a confrontationally populist image, if there ever was one. Similarly, Indian Warrior depicts a jaguar-costumed Aztec warrior plunging a knife through a chink in the armor of a 16th century Spanish conquistador, proving that populist resistance was nothing new to Mexico. As a nod to his new American surroundings, Rivera painted murals titled Frozen Assets and Electric Power showing, respectively, workers toiling beneath an easily recognizable New York City skyline and other workers literally boxed within the works of a Hudson-side electrical plant. Rivera never missed an opportunity to remind viewers (and rich patrons) of the human core to the mechanized modern world.

The mural that struck me the most powerfully was Rivera’s The Uprising (shown above). The fierce woman in the center fending off a soldier—while still clinging to her baby as other protesters struggle behind and below her—stands for every person of every age struggling against powerful forces of oppression. You don’t need to know anything about Mexican politics of the early 20th century to read the conflict and to hope for the right resolution. Watching the recent crackdowns on Occupy camps across America, I couldn’t help but superimpose Rivera’s leading lady on those sad scenes of civil unrest turned violent.

The planners of Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art couldn’t have anticipated the Occupy movement, but the timing of this exhibition couldn’t be more perfect. Rivera’s murals occupy the MoMA and our imagination with scenes of the past’s almost primal struggles between the powerful and powerless and give us hope that a better tomorrow might come from it. For many, the end of the Occupy movement and its aspirations seems “written on the wall,” but the dreams “written” on these walls by Diego Rivera eight decades ago refuse to go away.

[Image: Diego Rivera. The Uprising. 1931. Fresco on reinforced cement in a galvanized-steel framework, 74 x 94 1/8” (188 x 239 cm). Private collection, Mexico. © 2011 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.]

[Many thanks to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for providing me with the image above and other press materials for Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art, which runs through May 14, 2012.]