Dissecting de Kooning at the MoMA

Is it better to burn out, as Neil Youngsang, than to fade away? When it came to the drama of the Abstract expressionists, Jackson Pollock burned out like a supernova in a fatal drunken driving accident while Willem de Kooning’s light faded away slowly into the long night of Alzheimer’s disease. In de Kooning: A Retrospective, which runs at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City through January 9, 2012, the artist returns to his rightful spotlight in an amazing exhibition featuring 200 works ranging across seven decades of work—both before and beyond the AbEx years. Organized by John Elderfield, the MoMA’s Chief Curator Emeritus of Painting and Sculpture, this retrospective dissects every aspect of de Kooning and detaches him from the label of Abstract Expressionist to free us to see de Kooning as the truly versatile and vast artist he was.

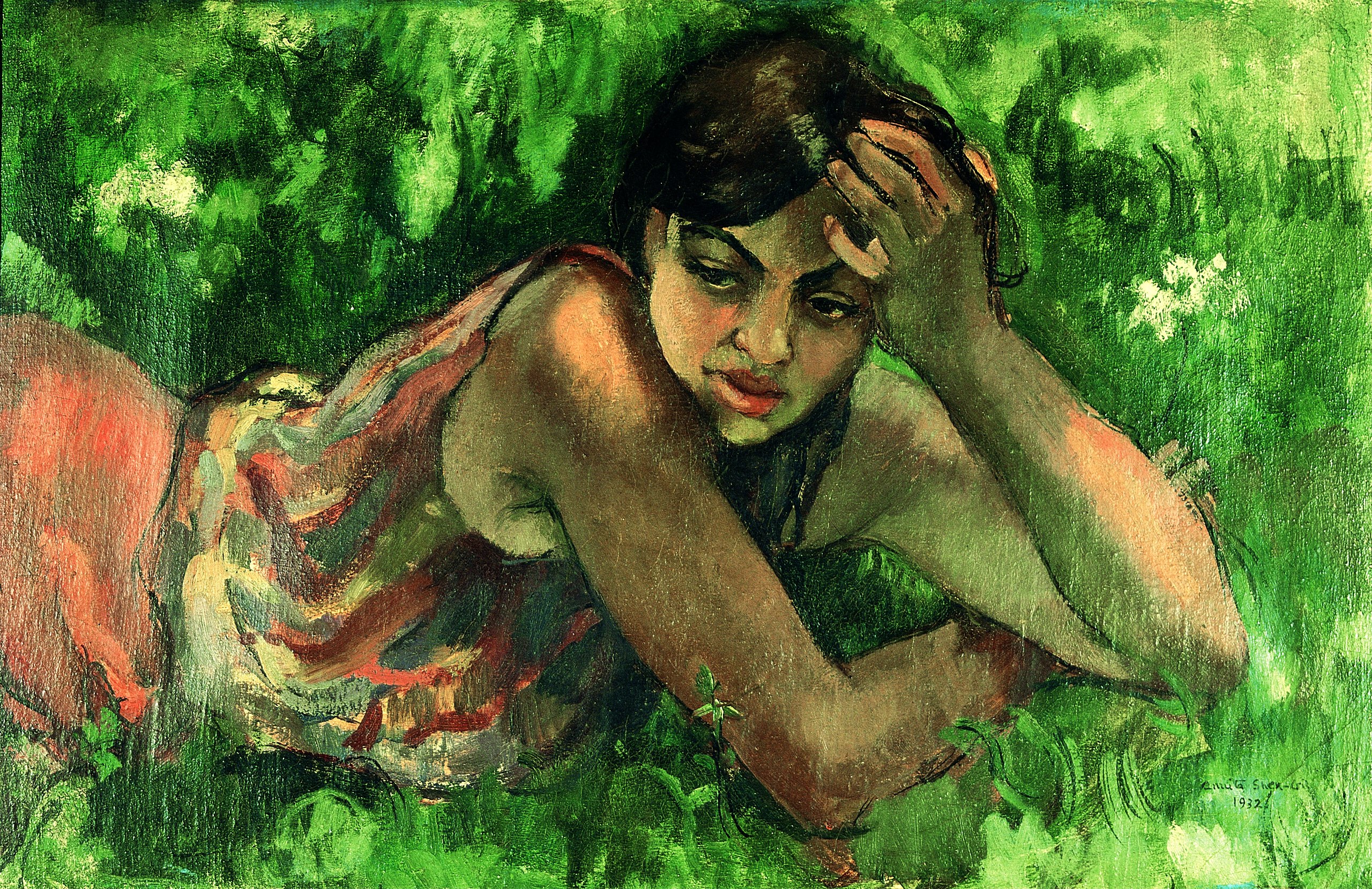

In Elderfield’s masterful introduction to the catalog, he analyzes de Kooning’s relationship to the past in his art. “For de Kooning,” Elderfield writes, “that [art] history, which preceded him, was unacceptably confining; and its continuing influence has impeded appreciation of his own originality.” Rather than struggle with the anxiety of influence, de Kooning sought to break free from that influence. Unfortunately, de Kooning’s reputation continues to be held in thrall by his art historical connections, both to the past and to his post-war contemporaries. de Kooning loved the art of the past, as Elderfield points out, “because it was not reductive and prescriptive, as modernist movements tend to become.” The trick for de Kooning was in “how to be a modern painter without surrendering the past—or, rather, without surrendering a past chosen by the painter for himself.” The past de Kooning chose for himself was what he called “the vulgarity and fleshy part” embodied by Titian, Rubens, Rembrandt, Soutine, and others. Call de Kooning an Abstract Expressionist, if you must, but never forget that he was much, much more for much longer than any of his fellow AbEx figures.

The greatest strength of the show is in giving us the whole de Kooning in his full breadth and depth, beginning with early still lifes from his teen years all the way up to the final works in the 1980s as he struggled to maintain some control over his mind. Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan’sDe Kooning: An American Master may remain the standard biography, but the catalog to this show should become the standard visual guide to de Kooning. Organized into themes, periods, timelines, and methods and materials (technical analyses), the catalog surrounds de Kooning with scholarship and infectious enthusiasm for his art. (The MoMA’s exceptional exhibition website is the next best thing to reading the catalog or seeing the show; click the links for themes, etc., to see the site.)

One of my favorite sections of the show is “New Directions,” which recounts de Kooning’s turn to sculpture in the late 1960s and infatuation with printmaking after a trip to Japan in 1970. Seated Woman on a Bench (shown above, from 1972) epitomizes this fascinating stage in de Kooning’s career. de Kooning formed the sculpture’s hands by filling his work gloves with wet clay. As a final touch, he pulled the left arm off and draped it over the woman’s head and shoulders. Despite their solidity, writes Jennifer Field, researcher at the MoMA and The Willem de Kooning Foundation, de Kooning’s sculptures “appear boneless, as if composed merely of thick skins and sinew.” Field quotes artist Georg Baselitz saying of de Kooning’s sculptures that “[t] hey don’t have muscles, or skeleton, or skin. They only have a surface that doesn’t have any content…” In this way, de Kooning’s sculpture reveals as much about his painting as the sculptural works of predecessors Degas, Matisse, and Picasso revealed about their painting. After looking closely at these all-surface, content-less figures, you’ll never look at de Kooning’s controversial Women paintings (generously represented in the exhibition) again. If the recently late Lucian Freud gave modern figurative art big boned bodies, de Kooning deboned them and made art out of pure, “vulgar” flesh.

If nothing else, de Kooning: A Retrospective should put to rest the lingering notion that de Kooning died artistically when Abstract Expressionism fell out of favor. “The purported decline,” Elderfield explains, “was in the artist’s control of his medium,” which makes it ironic “that what had previously been mistakenly praised, his supposed de-skilling, was now mistakenly condemned, for de Kooning remained very much in control.” This retrospective puts de Kooning back in control of his reputation, maybe even of his position in the pantheon of art history. Few exhibitions (or catalogs) can claim to make an already famous artist rise to the top tier of all art history, but de Kooning: A Retrospective might actually do exactly that.

[Many thanks tothe Museum of Modern Art in New York City for providing me with the image above, press materials, and a review copy of the catalog to de Kooning: A Retrospective, which runs through January 9, 2012.]

[Image:Willem de Kooning (American, born the Netherlands. 1904-1997). Seated Woman on a Bench, 1972. Bronze. 37 3/4 x 36 x 34 3/8″ (95.9 x 91.4 x 87.3 cm). Private collection. © 2011 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.]