Summer Reading on the U.S. Economy

For me, summer is a time to catch up on my reading. As I head out for a few weeks of vacation, I thought I would leave you with a few suggestions for things I thought were worth reading that you may have missed. Today, I’m going to share some of the pieces—mostly charts and graphics—relating to the state of the U.S. economy that I found most striking this year.

I want to start by linking to Catherine Rampell’s graph (The New York Times, July 8)—updated after the latest anemic job report—comparing the rate at which employment recover during and after recessions. The graph dramatically illustrates just how much deeper job losses have been during this latest economic downturn than during other recessions over the last forty years, and how slow jobs have been to return.

In “The Phantom 15 Million,” Jim Tankersley (National Journal, January 21) points out that even if the U.S. hadn’t gone into recession in 2008—wiping out virtually all of our job gains for the decade—the U.S. still would have had 15 million fewer jobs than economists expected. At the beginning of the decade, many economists expected the economy to create 22 million jobs by 2010. But even before the recession it had only created 7 million new jobs. It’s unclear why the economy is no longer creating as many jobs as it used to, or why U.S. businesses are sitting on cash now rather than hire new workers. But part of the problem, Tankersley suggests, is that the U.S. is no longer investing enough in education and job training.

Perhaps, some economists theorize, the United States isn’t creating innovative jobs because its workforce isn’t up to the challenge. For probably the first time in history, our young adults are no better educated than their parents. Nearly all our international rivals, in developed and developing economies alike, continue to make generational leaps in college graduation. Brainpower is still our comparative advantage with the rest of the world, but the advantage is shrinking.

Next, take a look at the charts (The Washington Post, June 23) that Ezra Klein claims show that we have “a Congress problem, not a deficit problem.” The charts use Congressional Budget Office data to show if Congress simply did nothing the deficit would disappear when the Bush tax cuts expire as scheduled. The deficit problem arises only if Congress extends the Bush tax cuts again or passes another “doc fix”—as it is expected to do—maintaining Medicare reimbursement rates. Future deficits, in other words, are largely created by what Congress plans to do.

Then look at this chart, also from Ezra Klein (The Washington Post, July 12), which shows that the deficit is caused as much or more by the Bush tax cuts as by increased spending on the stimulus package and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. To get a sense of how low taxes in the U.S. are right now both by international and by historical standards—as well as how regressive recent tax cuts have been—take a look at this revealing collection of tax charts (April 14) from The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

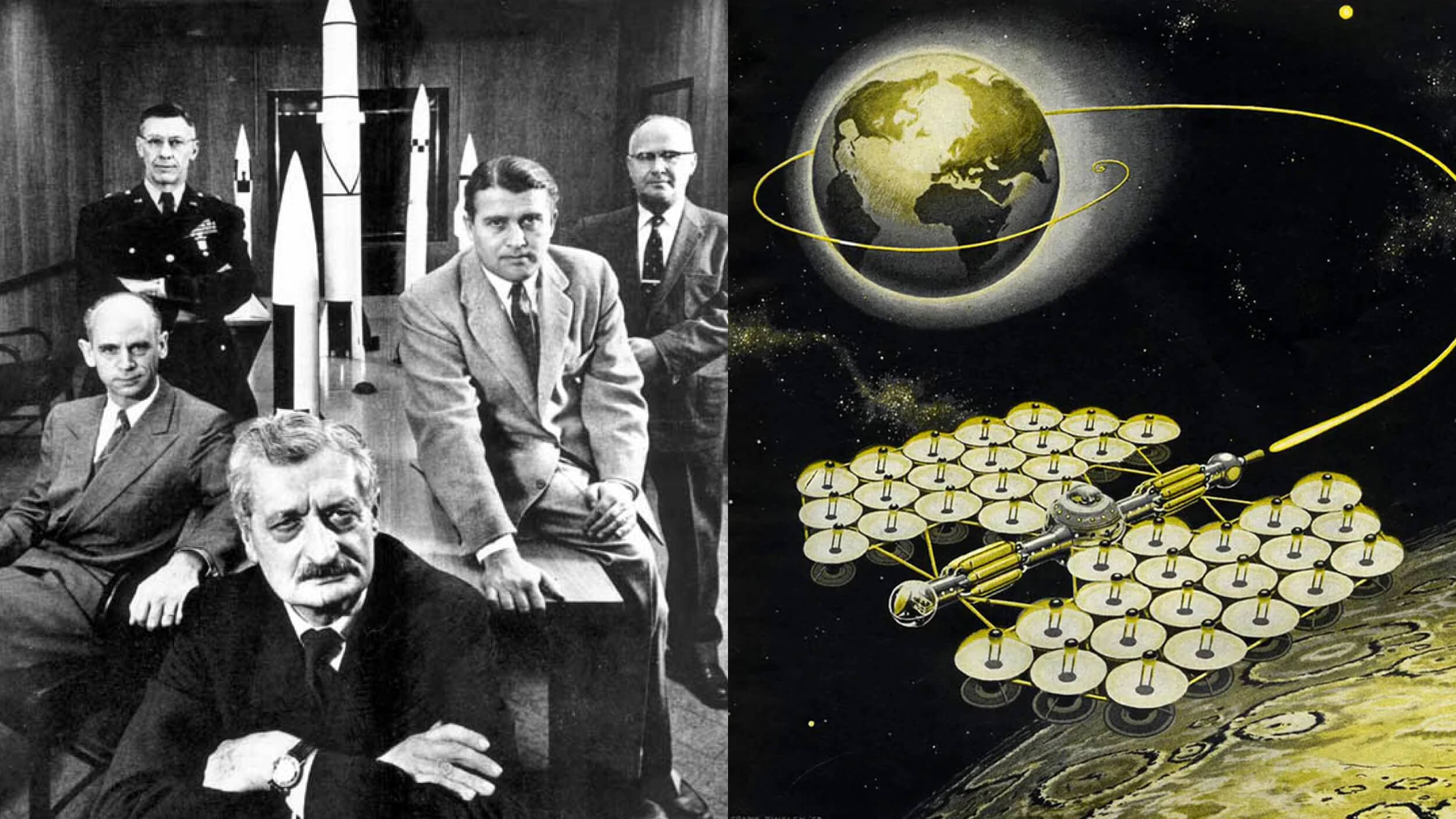

Photo credit: Fletcher