How Cy Twombly’s Inner Child Lives on

When I found out today about the death of American artist Cy Twombly at age 83, I quickly ran a gauntlet of reactions: one, I have to write about him; two, how do I write about the one major American artist I (like many others) just don’t “get.” The scribbles and seemingly random marks of Twombly’s art just didn’t speak to me, regardless of how hard I strained to hear them. Now that the man is gone and the art remains, I feel compelled to give him one more try. Twombly, the stereotypical “My kid could do that!” modern artist, is dead, but maybe the inner child he channeled in his work lives on.

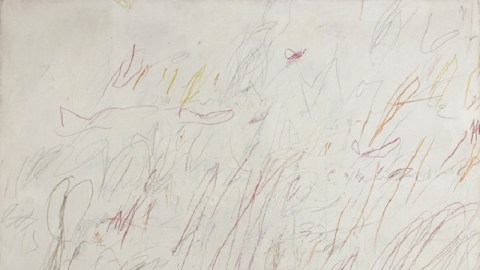

On my last visit with the family to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, we wandered into the gallery in which Twombly’s Fifty Days at Iliam has been permanently displayed since 1989. My sons seemed bemused by the crayon scribbles alluding to Homer’s Iliad, specifically Alexander Pope’s translation, at least according to Twombly. My wife, not a fan of modern art in general, lost patience quickly. My thoughts wandered back to the hour many years before I once spent in that gallery—a self-enforced, prolonged exposure in hopes of finally coming to some understanding of Mr. Twombly’s art.

Surrounded by the alleged allusions to the last days of Troy, I found myself going through the art lover’s version of the Kübler-Ross model of “The Five Stages of Grief.” I ran through denial (“How can this be considered art?”), anger (“Fraud!”), bargaining (“Maybe if I stay here a little longer, I’ll understand…”), depression (“I’ll never figure this guy out.”), and finally acceptance (“Let’s just agree to disagree, Cy.”). An acquaintance of mine at the Philadelphia Museum of Art told me that one of his first duties as a curator was to look at the modern art each morning for signs of vandalism. The Twombly gallery was a nightmare for him as he searched for new random marks among the sea of scribbles and random marks meant to be there. I searched works such as Sunset (shown above) for something resembling or suggesting a sunset to no avail, as if Twombly vandalized the very idea of sunsets. I felt that I would never crack the “Cy Code.” The only redeeming feature of Twombly’s biography remained the fact that his father once pitched for the Chicago White Sox.

“It took me four years to paint like Raphael,” Picasso once said, “but a lifetime to paint like a child.” Picasso’s “child,” however, knew how to stay inside the lines. Twombly’s “child” didn’t know how to do that yet. Twombly enjoyed the simple gesture of making marks the way that a child does, free of lines and other confinements. I wonder whether Twombly’s stated allusions to Pope or Rilke were smokescreens or honest jumping off points for the exuberant explorations of his “inner child.” Twombly took Pope’s measured couplets and scribbled crayons all over them, just like a real, non-idealized, non-Picasso child would—reveling in the story itself rather than the artifice of the telling. Maybe I’ve failed to embrace Twombly because I’ve lost that childlike innocence and joy. With the passing of Twombly today, we should all look at the inner child he unleashed upon the world of art and see if we can find our own inner child.

[Image: Cy Twombly. Sunset, 1957. Oil, pencil, and crayon on canvas. 142.5 x 195 cm. © Cy Twombly.]