The Choices That Mean Life or Death: Osama’s Crucial Decisions

What is it about power that changes people – or if not changes, brings out those aspects of them that had heretofore lain dormant? As the old adage goes, power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. While this may be true, is it just corruption that happens, or something else, something more internal and fundamental, that changes one’s outlook, one’s decisions, one’s calculations on the likelihood of each decision’s success or failure?

These were the questions that went through my mind as I read this latest column by David Brooks, exploring the riddle that is Osama Bin Laden. I realize that people are likely reaching the Osama saturation point, with the explosion of all media coverage since the weekend’s events, but here, I want to consider a more psychological angle, from the view of decision science: what we can tell about someone from the choices they make.

What do we really know about Osama bin Laden, the private man? Past a certain point, not much. It does no good to speculate, to project, to draw conclusions on some deep-rooted personality or motivational impulses. I’m not Freud, and Osama was never on an analyst’s couch. But we do know some personal facts and we do have the objective reality of certain decisions that the leader made. And so it is to those decisions, that can be taken without the internalizing bias necessitated by psychoanalytic approaches at a distance (in other words, of a man whose private life has for so long been so much of a secret), that I propose we turn to understand at least some small part of the person behind the symbol. It’s well worth doing, because as Brooks put it, individuals matter.

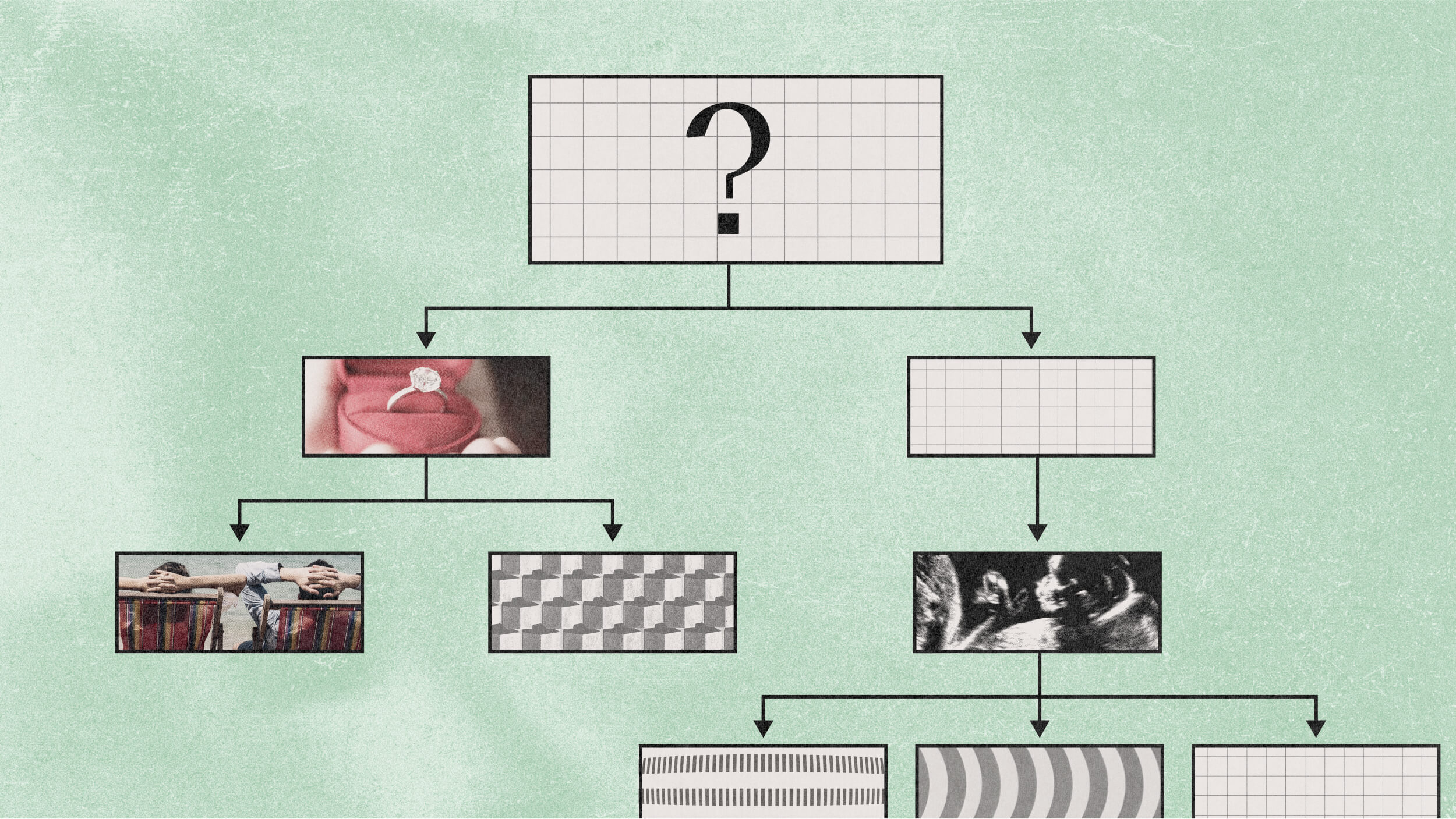

The influence of power on choice: the case of Bin Laden

At least from the little we know about Osama’s early life, it seems that power did in fact change him, corrupt him, even, depending on your view of what is and is not permissible under certain religious tenets. Fact one (courtesy of Brooks): he wanted to head the Saudi response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and he wanted to run the family business. This was in 1990. He was 33. He had no past political leadership experience. He had no past business experience. Why, then, did he think himself not only capable but worthy of taking on these double mandates of leadership – and why was the rejection that followed so much of a shock?

What comes out of these decisions is a feeling not just of entitlement, but of something more, of the beginnings of a belief in innate superiority coupled with inviolability: I deserve it; I am capable of it; and no one dares to not give it to me, whatever the it might be. In such a view, Osama is not alone. A long list of leaders, from the dictatorial (Stalin) to, perhaps, even the democratic (FDR? I’m not trying to be political here, or to comment in any way on his leadership tenure, other than to say that you might be able to see similar patterns in decision such as that unprecedented, even in times of war, third term. Perhaps a better—or at least less controversial—example would be Nixon) have given off the same aura of entitled untouchability.

Then there is the question of how the Al Qaeda movement was set up to begin with. What kind of a person thinks that he is worthy of being a symbol, and takes it upon himself to make that known? How do you have to see yourself to think that you, in your own life, are enough to carry the symbolic burden of a movement?

Finally, and most concretely, we have the choices that led up to Bin Laden’s death, those decisions that may have meant the difference between life and death, continued leadership and capture. There is the choice of a house. Why a house, all of a sudden, and a million-dollar compound at that? Is that discrete? Effacing? Difficult to track? What ever happened to the mountains? It seems that something shifted in Osama during his tenure, lending him to disregard the obvious pitfalls of such a comparatively risky choice of abode.

And then there is the choice not to move, to stay put in the chosen location for years. Even if the original logic of the choice were sound, surely it benefits one to remain mobile. That seems to be an elementary rule of strategy, tactics 101, so to speak. A moving target is hard to hit. A still one, not so much.

Closely related is the choice to keep the same people close. I understand the difficulty of earning someone’s trust, of training new recruits, of replacing old and tried confidantes. But again, isn’t that degree of constancy toward the dangerous side of things? How long until someone thinks to track one of your known deputies directly back to you, especially if that someone has been known to employ such tactics in the past?

One has to wonder: earlier in his tenure, would Bin Laden have been more careful? Did his powerful position alter in a profound way his decision calculus?

The invincibility of the fate-favored powerful few

To me, these decisions, the ones that ultimately facilitated Bin Laden’s capture, speak overwhelmingly of a belief in inviolability, or something close to it. I won’t be caught. I haven’t been caught, and I never will be, because I am who I am. Not to sound overly simplistic, but once again, that type of behavior is not new. To draw once more on US domestic politics, I see parallels to a Spitzer, who thinks no matter how blatant his abuses, he won’t be caught, or a Tiger Woods, for that matter, or even a Bernie Madoff – all powerful people, who, once in power, made judgment lapses that seem idiotic for someone of their caliber, idiotic in the sense of the belief that they would not be caught – and the extent of the disbelief when they finally were. The rush of blood to the head, the heady recklessness of authority, the thrill of realizing the extent of your influence: whatever it is that makes the powerful act as they do.

It may be difficult if not impossible to predict when a shy, devout boy will grow into the leader of a terrorist network. But one thing is more apparent: once in a powerful political position, he is likely to make judgments that display a greater degree of confidence, even, perhaps, arrogance, than before, and in so doing, make mistakes that could prove to be costly.

Consider what Gail Collins wrote of President Obama, in her discussion of the soon-to-be-iconic war room photograph: that he thinks he is favored by fate. As she puts it, “But he’s also lucky. People partly make their own fortunes, but I wonder if he’d have had the confidence to take such a huge gamble if he didn’t believe innately that he’s the kind of guy fortune favors.” The same, it seems, can be said of Osama: a belief in his lucky stars, in being the kind of person who can gamble and come out ahead, time and time again. The lucky son of fate, who can be right under your noses and not be found.

Or perhaps it wasn’t that he thought he was fate’s favorite. Maybe instead of fate, it was fatalism, a sick old man ready for it all to be over. We’ll never know for certain.