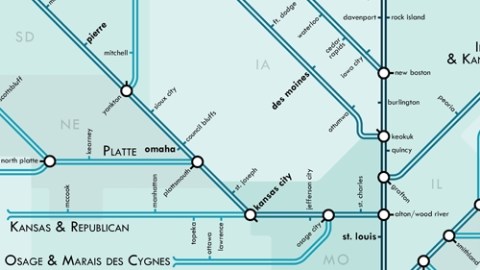

Mississippi Metro Map

Rivers are magical, liminal places. Prehistoric man, in awe of their transportational qualities, threw in swords and other valuables as votive offerings to fluvial deities. The Greeks provided their dead with coins as fare for Charon, who ferried them across the river Styx to the Underworld. Rivers and their liquid, ever-changing names and meanings, are the backbone of Finnegan’s Wake, James Joyce’s last – and least readable – book.

Rivers both connect and divide; not just the sublunar and the supernatural, also different parts of the real world. They’re mankind’s first highways, linking up all points on either shore along the navigable stretch between estuary and source. But rivers are also nature’s ready-made borders, seized upon by surveyors and mapmakers as obvious dividing markers (1) for the land they irrigate.

One of the best examples of the river’s myriad functions is the Mississippi. Springing in Minnesota and merging with the Gulf of Mexico at the southern tip of Louisiana, this is an all-American river. Yet it is also a frontier stream – forming part of the border of no less than ten US states.

Old Man River also divides the country in two distinct halves, underlined by differences in agricultural patterns, population density, and even the squareness of states. It’s no coincidence that the Gateway Arch, symbolic portal to the West, is located in St. Louis (2).

At the same time, the Mississippi is also a great unifier. Its basin covers 40% of the continental United States, the rivers and other waterways it connects extend across 31 states, enabling commerce between places flung far across the North American continent.

This map shows that riverine network in the manner of Harry Beck’s oft-imitated 1930s London Underground map (3). Like Beck’s map, this one uses straight lines, and a limited choice of angles (45˚ and 90˚) to simplify geography for the benefit of clarity. At one glance, the whole tangled mess of tributary rivers, and twists in the main river itself, becomes much clearer.

This map, also indicating major cities and places of confluence, looks like it shouldn’t be too hard to memorise, even. Only four rivers drain into the Mississippi from the east, while six rivers form a confluence on its right bank (4).

On the eastern shore, these are (north to south):

- the St. Croix river, at Hastings, MN;

- the Wisconsin river, at Prairie du Chien, WI;

- the Illinois river, at Grafton, IL (treated as one river system together with its tributary, the Kankakee river);

- the Ohio river, at Cairo, IL (the Ohio’s major tributaries mentioned here number a dozen).

On the western shore (north to south):

- the Minnesota river, at Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN;

- the Iowa river, at New Boston, IL (joined near the end of its course by the Cedar river);

- the Des Moines river, at Keokuk, IA;

- the Missouri river, near Alton an Wood River, IL (the Missouri, the Mississippi’s largest tributary, is actually longer than the Mississippi itself, and boasts several large tributaries of its own);

- the Arkansas, at Rosedale, MS (again a mighty river with many of its own tributaries; to elaborate on the liminal/supernatural theme: Rosedale is where Robert Johnson is supposed to have sold his soul to the Devil, a story told in Cross Road Blues);

- the Red river, at Simmesport, LA.

Many thanks to Michael Donatz for sending in this map, which in honour of Thomas Jefferson’s never-realised state of Metropotamia (literally, ‘land of the mother river’), and to avoid litigation by the Tube map people, could be called the Mississippi Metro Map (original context here, on the blog Something About Maps).

Strange Maps #501

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

——-

(1) this is less straightforward than it might seem. First there is the issue of where to draw the border. Right down the middle is the most obvious way, but this is less easy to police than the other solution: on one of both shores. This, however, can lead to pretty bizarre border situations, as mentioned in the comments section of an earlier post on the Twelve-Mile Circle. Placing borders in rivers is a sign of surveying laziness, or at best short-sightedness, as flowing water tends to shift over time. Do borders move with the river, leading to complicated claims for territorial compensation, or do they stay behind, creating a maze of enclaves on either side of the river’s new course?

(2) the westernmost eastern city in the United States, or its easternmost western city – both labels have been applied to St. Louis.

(3) inspiring several other maps discussed on this blog.

(4) As the Mississippi flows north to south, the eastern shore is its left bank, and its western shore the right bank.